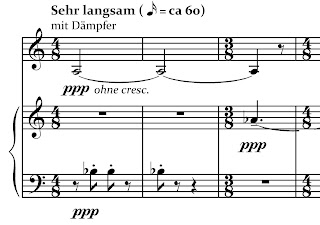

I've been collecting some challenging music for a young violinist, a daughter of a good friend, to play. During my search, I spent some time with Anton Webern's Four Pieces (Vier Stücke), Op. 7, which, dating from 1910, are no longer functionally tonal but at the same time are still some several important steps away from the formalities of the twelve tone technique Webern would eventually franchise from his teacher, Schönberg. Like other works of this moment — often identified as "free atonal" — it is fascinating to hear music with such a coherent body of techniques but applied with improvisatory spontaneity and no compulsion to submit to strict restrictions. There are some awkward moments here, for example in the use of octave dyads in both the piano and the violin, which come across as fairly heavy-handed orchestration, and I'm not altogether certain that the second — and most complex — piece works at all, but for the most part, this is music sensitive to every detail, espressive but not pumped to the level of the hyper-expressionism of Schönberg. Recalling traditional tonal practice, if only emblematically, single tones aquire local and global importance if not exactly tonicization, there are numerous small repeated patterns and some substantially long sustained tones or chords, within and against which the sensual aspects of tone combinations are far from forgotten (as in the opening of the third piece, in which the violin sustains a low "a" for about 20 seconds, during which the piano strikes tones which create vivid acoustic beating (in Mikrokosmos, Bartók used the word "buzzing" for the same technique)).

Looking forward to future concerns, the pitches used tend to fill up clusters of neighboring semitones, with new pitches tending to complement neighbors, but unlike full-blown twelve-tone music and quite a bit like some music of Wolpe or Feldman, there is no regular consumption of entire twelve-tone collections. With such an abundances of semitones, and semitones displaced by one or more octaves, this music is filled with leading tones and, indeed, the tonal practice retains other important voice-leading features: melodies, while not quite tunes, have clear contours, with melodic leaps either turned into arpeggios or met by compensatory motion in the opposite direction, and the relationship between voices — yes, this is still music in which one hears voices — exhibits elegant voice leading, for example in the use of contrary motion between the pianist's hands. Contour and register are often the most important elements; the registers chosen for the individual instruments tend to frame each other, with tactical use of empty registral spaces. Little details matter here in a big way: the fourth piece closes with a descending arpeggio from high up in the violin, very quietly, am Steg, and marked "like a breath" (wie ein Hauch) which repeats even more quietly, but metrically displaced from the downbeat to a pickup. That little bit of displacement literally takes your breath away. With my recent thoughts about the not-yet-tonal, it is a pleasure to spend time with some music that is no-longer-tonal, but not-yet-completely-not-tonal, and thus, still open to a rich variety of potential alternatives.

Looking forward to future concerns, the pitches used tend to fill up clusters of neighboring semitones, with new pitches tending to complement neighbors, but unlike full-blown twelve-tone music and quite a bit like some music of Wolpe or Feldman, there is no regular consumption of entire twelve-tone collections. With such an abundances of semitones, and semitones displaced by one or more octaves, this music is filled with leading tones and, indeed, the tonal practice retains other important voice-leading features: melodies, while not quite tunes, have clear contours, with melodic leaps either turned into arpeggios or met by compensatory motion in the opposite direction, and the relationship between voices — yes, this is still music in which one hears voices — exhibits elegant voice leading, for example in the use of contrary motion between the pianist's hands. Contour and register are often the most important elements; the registers chosen for the individual instruments tend to frame each other, with tactical use of empty registral spaces. Little details matter here in a big way: the fourth piece closes with a descending arpeggio from high up in the violin, very quietly, am Steg, and marked "like a breath" (wie ein Hauch) which repeats even more quietly, but metrically displaced from the downbeat to a pickup. That little bit of displacement literally takes your breath away. With my recent thoughts about the not-yet-tonal, it is a pleasure to spend time with some music that is no-longer-tonal, but not-yet-completely-not-tonal, and thus, still open to a rich variety of potential alternatives.

1 comment:

I think you're onto important issues here, Daniel. Years ago, I gradually came to feel more and more that the whole notion of a 'crisis of language' that would have come with atonal practice is extremely misleading and has led composers to confuse languages and compositional methods (and leading to sometimes very arbitrary ideas about how to 'construct' a language - you find this tendency among academic modernism just as much as with people who decide to write in what they think of as an 'accessible' style).

Whereas in early free atonal works it's so clear that works, in all the aspects of musical thought, are constantly referring to existing musical language.

My own stock example is the opening bar of Schoenberg's op. 11 nr. 1, which so clearly uses a suspension-resolution type setup, even if it doesn't use a conventional interpretation of the 'consonance' that it should resolve into. (Functionally it sounds much like the opening of Tristan to me).

Post a Comment