I'll be on the road and away from blogging for the next few days, so to fill in that absence, here's a fine talk by Robert Ashley on The Future of Music. I profoundly disagree with him on one important point (I think that music -- unlike hamburgers, automobiles, oil, grain, currency and under-paid labor -- has the possibility of opting out of commodification) but Ashley manages to shoot down all the cardboard ducks in the Geater Musicland Arcade and does so with even more than his usual brio. (Here's one of Ashley's money quotes: "The string quartet was the sampler that ate hamburgers.")

And if that's not enough, here's an online video of a lecture by Robert Irwin, an artist who left his studio behind and has never turned back.

A displaced Californian composer writes about music made for the long while & the world around that music. ~ The avant-garde is flexibility of mind. — John Cage ~ ...composition is only a very small thing, taken as a part of music as a whole, and it really shouldn't be separated from music making in general. — Douglas Leedy ~ My God, what has sound got to do with music! — Charles Ives

Friday, March 30, 2007

One last rant before I go

A friend just tried to hit me with the old argument about pop music's profound invention of the concept album. I tried to hold my tongue (I blog with Via Voice) but just couldn't let it go. So here's the rant:

Commercial popular music is fundamentally conservative; it never innovates, it incorporates. "The concept album", for example, much praised as an innovation of 1960's pop was in fact the invention of Robert Schumann. The origin of the record album in a sheet music genre just happens not to have a place in the shallow memory of pop, which barely remembers that an album was initially required as a container for 78s of classical music which went beyond the time limits of the discs. Pop music is completely fixated on the recorded commodity, which may be re-packaged but only under great constraints, re-imagined. The identification of a piece of pop music with specific emblems or artifacts of its recorded form is near-complete. Live performers strive to reproduce studio recordings. Even a "cover" of a pop song -- the genre in which pop music approaches an interpretive art -- is measured precisely by the amount of material in the original recording that has been replicated and the degree of fidelity to it, with only the most extraordinary acts of great license from that fidelty tolerated. This contrasts to notated music in which the notation may suggest an ideal, but notation is never unambiguous and can only ever be approached and realized by interpretation. (Recall Richard Winslow's Law: if you want to reproduce something precisely, transmit it aurally; if you want to guarantee that something changes over time, write it down). Over the years, many composers of serious music have ventured into pop music; the results are not always pretty (anyone else remember The United States of America or The Open Window or Elephant Steps?) There's much talk about a need for art music to appropriate the "energy" of pop, but that's only a short-term move, as the capacity of pop for forward drive and amplitude will always be greater. Art music, on the other hand, has a larger capacity for containing information, and sometimes that's a useful quality.

Don't get me entirely wrong -- there is always room in life for a song and a dance, and popular music can do both superbly. Contemporary art song, for example, is always going to have an existential problem alongside the songbooks of a Randy Newman or a Roy Orbison. But art music has the luxury to push our comfort zones a bit beyond the everyday song and dance, and by taking advantage of that luxury, the two genres can thrive in a relationship that is complementary and not parasitic.

Commercial popular music is fundamentally conservative; it never innovates, it incorporates. "The concept album", for example, much praised as an innovation of 1960's pop was in fact the invention of Robert Schumann. The origin of the record album in a sheet music genre just happens not to have a place in the shallow memory of pop, which barely remembers that an album was initially required as a container for 78s of classical music which went beyond the time limits of the discs. Pop music is completely fixated on the recorded commodity, which may be re-packaged but only under great constraints, re-imagined. The identification of a piece of pop music with specific emblems or artifacts of its recorded form is near-complete. Live performers strive to reproduce studio recordings. Even a "cover" of a pop song -- the genre in which pop music approaches an interpretive art -- is measured precisely by the amount of material in the original recording that has been replicated and the degree of fidelity to it, with only the most extraordinary acts of great license from that fidelty tolerated. This contrasts to notated music in which the notation may suggest an ideal, but notation is never unambiguous and can only ever be approached and realized by interpretation. (Recall Richard Winslow's Law: if you want to reproduce something precisely, transmit it aurally; if you want to guarantee that something changes over time, write it down). Over the years, many composers of serious music have ventured into pop music; the results are not always pretty (anyone else remember The United States of America or The Open Window or Elephant Steps?) There's much talk about a need for art music to appropriate the "energy" of pop, but that's only a short-term move, as the capacity of pop for forward drive and amplitude will always be greater. Art music, on the other hand, has a larger capacity for containing information, and sometimes that's a useful quality.

Don't get me entirely wrong -- there is always room in life for a song and a dance, and popular music can do both superbly. Contemporary art song, for example, is always going to have an existential problem alongside the songbooks of a Randy Newman or a Roy Orbison. But art music has the luxury to push our comfort zones a bit beyond the everyday song and dance, and by taking advantage of that luxury, the two genres can thrive in a relationship that is complementary and not parasitic.

Wednesday, March 28, 2007

Words, Work, War and Song

I haven't made as much vocal music as I'd like, and the problem usually lies with finding the right text. And finding a text that welcomes a musical setting is often more a problem of managing abundance than of scarcity. There are simply too many words that invite a link to music, and music usually prefers a few excellent words to many good ones.

Blogger Patrick Swanson did me a great favor recently, suggesting that I set some of Virgil's Georgics. He did an even greater favor and selected a passage to get me started:

N.O. Brown, my teacher wrote his own Georgics, a text in praise of work, both earth- and handwork, as in Virgil's great poem about agriculture, and work of the imagination. I'd now like to do a couple more songs like this, a kind of cantata, if one can use that word anymore.

Blogger Patrick Swanson did me a great favor recently, suggesting that I set some of Virgil's Georgics. He did an even greater favor and selected a passage to get me started:

Scilicet et tempus veniet, cum finibus illisThis is clearly my kind of text -- with words that mean a lot in both the long and short-haul -- and finally a chance not to shy away from saying something about the war. Scanning the Latin meter was a pleasure and I set it right away as a little song (3'15" or so) for unison voices, harp, and optional percussion (bamboo clappers and metal things).

agricola incurvo terram molitus aratro

exesa inveniet scabra robigine pila

aut gravibus rastris galeas pulsabit inanis

grandiaque effossis mirabitur ossa sepulchris.

(Be sure of this: the time will come when in those fields,

the farmer working the earth with curved plough,

will unearth rough weapons eaten by rust,

or strike the side of an empty helmet with his heavy hoe,

and wonder at the bones of great ones now untombed.)

N.O. Brown, my teacher wrote his own Georgics, a text in praise of work, both earth- and handwork, as in Virgil's great poem about agriculture, and work of the imagination. I'd now like to do a couple more songs like this, a kind of cantata, if one can use that word anymore.

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

Evil Villagers Go Digital

The august firm of Austrian piano-makers, Bösendorfer, are now making a digital instrument. While it's fine to have a Bösendorfer keyboard and action fronting for an otherwise electronic instrument, and the Vienna Symphonic Library-made samples are very good, it's still basically playing a set of samples, and even with increases in memory size and computing speed, a sample set is still going to do a poor job with a number of subtle but still characteristic physical interactions that go into a complex instrument like the piano (sympathetic resonances, cancellations, interference beating etc.). On the other hand, there may very well be an aesthetic which looks kindly on instruments without such pronounced secondary effects, in which case this instrument can certainly be used.

Prosaic

From time to time, I've made prose scores, scores in which the instructions to the players are in words rather than in a conventional music notation. I did this a lot more in the past, especially when I was working in learning environments. A prose score is often an efficient way to get into some aspect or another of sound or of music-making. Sometimes these scores were musically sufficient in and of themselves, and sometimes they were points of departure for more conventionally notated works. (A collection of my prose scores from the 80's can be found here).

I've recently begun some etudes for instruments, beginning with the piano, and the beginning of these explorations is a set of three prose scores for the Swiss pianist Hildegard Kleeb. In addition to her concertizing, she teaches piano to young people, and I imagined these three pieces (Dr WOLF's Complete & Correct SCHOOL of PIANO LEVITATION) might be of use to young hands and ears. These might eventually work themselves into a more fixed and/or conventionally notated format, but who knows? (A PDF file is here).

I've recently begun some etudes for instruments, beginning with the piano, and the beginning of these explorations is a set of three prose scores for the Swiss pianist Hildegard Kleeb. In addition to her concertizing, she teaches piano to young people, and I imagined these three pieces (Dr WOLF's Complete & Correct SCHOOL of PIANO LEVITATION) might be of use to young hands and ears. These might eventually work themselves into a more fixed and/or conventionally notated format, but who knows? (A PDF file is here).

Monday, March 26, 2007

eBay Commissions

Celeste Hutchins has joined Dennis Báthory-Kitsz in offering commissions via eBay. This is probably one of the ways in New Music is going to move and Dennis and Celeste are real pioneers, so summon your own pioneering spirits, step up, and give 'em a commission.

(I'm not quite ready to join the eBay-ers myself, as I still enjoy negotiating with mysterious commissioners with obscure accents and loud ties via messenger pigeons, late-night Ham radio broadcasts, and sometimes even an actual rendezvous or two in the back room of my favorite billiard parlor. (I admit that it's not good bidness sense but, for some reason, still like to think of the whole artist/patron cha-cha as something romantic in a world starved for the same). In any case, having a variety of business models is a good thing. Isn't life grand?)

(I'm not quite ready to join the eBay-ers myself, as I still enjoy negotiating with mysterious commissioners with obscure accents and loud ties via messenger pigeons, late-night Ham radio broadcasts, and sometimes even an actual rendezvous or two in the back room of my favorite billiard parlor. (I admit that it's not good bidness sense but, for some reason, still like to think of the whole artist/patron cha-cha as something romantic in a world starved for the same). In any case, having a variety of business models is a good thing. Isn't life grand?)

Leedy: The Leaves Be Green, again

I've hosted an online copy of the manuscript score to Douglas Leedy's The Leaves Be Green. Stephen Malinowski has now made an edition (online here in PDF form) that is much easier on the eyes than my scan, and also has the score nicely lined-up to facilitate the introduction of extemporaneous repetitions of variations encouraged by the composer. The Leaves Be Green is a work for solo harpsichord or clavichord in (quarter-comma) meantone temperament, at once an hommage to an old traditon of keyboard variations, to South Indian tala cycles, and an excellent example of the range of west coast music experiment to boot.

Malinowski has also made an arrangement of The Leaves Be Green for viol quartet, ingeniously solving some intonation problems by using a quartet of two basses and two trebles. I can imagine that, without the built-in decay and sympathetic resonances of the keyboard instruments over the long tones, this will be quite a different piece, but nevertheless quite a beautiful one. If anyone is interested, I can provide copies of the scores and parts to this arrangement. Many thanks to Mr. Malinowski!

Malinowski has also made an arrangement of The Leaves Be Green for viol quartet, ingeniously solving some intonation problems by using a quartet of two basses and two trebles. I can imagine that, without the built-in decay and sympathetic resonances of the keyboard instruments over the long tones, this will be quite a different piece, but nevertheless quite a beautiful one. If anyone is interested, I can provide copies of the scores and parts to this arrangement. Many thanks to Mr. Malinowski!

Sunday, March 25, 2007

Strong Opinions

There's still quite a bit of uncertainty out there about how a web presence will play out in our changing Newmusicland. This blog has featured a lot of opinions issues of musical politics that can be reasonably characterized as strong, and I've received a lot of responses, but the vast majority of them have been email messages and many of the online responses have been anonymous.

For example, on the topic of boycotting competitions (in particular, those with high entry fees and low prizes), I have received 22 emails in support of my position and none against, and as gratifying as the echo was, it was a bit disturbing that not one of the 22 was willing to go public. While I might understand it if the emailer doesn't want to be associated in public with me (go google G. Marx on clubs, members, and having me as one), I dislike the idea that he or she doesn't want to upset the competition applecart by speaking out, and profoundly dislike the idea that she or he has chosen anonymity in order to preserve their own competition chances.

I have made a point here of blogging about composers with a diversity of approaches, idioms, and genres, often or even especially those doing work far different from my own. I happen to think that a musical diversity is essential, and I my curiosity about what windband, or choir, or liturgical, or film, or new age, or circuit-bending, or super-complex composers are up to is an honest one. Sometimes, this activity is personally more interesting than activity among musicians with aesthetics closer to my own. (One of my first postings here was about a composer with Asperger's syndrome; his rough approximations of late 18th century music brought out features of that music that I had missed). This has created a few very strong responses and some misunderstandings (I once defended Babbitt's right to compose the music that he wanted and was branded a 12-toner for my defense; unfortunately the brand has lived on in the eternity of internet publication). An anonymous comment recently slammed a composer I mentioned for writing "dreadful pseudo-romantic new age slop". Okay, but why the anonymity? and why not say a bit more about what, precisely, makes it dreadful? I may very well agree with you, but simply dropping a bomb and running away doesn't take us anywhere forward.

Personally, I think that Newmusicland is a microeconomy (or a series of microeconomies within a microeconomy) without much real at stake. Sure, there are prizes to win and teaching gigs to hand out, but in the end, it's a bloody struggle over bloody nothing, or a mad rush for crumbs (thanks to Joyce and Feldman), and even with the "best" resume and connections the distribution of laurels and better day jobs ultimately involves a large factor of the arbitrary. Establishing a public musical identity as a composer means taking a strong position, having strong opinions, and saying through our music in a very public way that I like this and (implicitly) not that. But are our strong opinions only to be placed in public in the form of our music, and not our words? When we switch to words, do we suddenly have a license to duck and cover?

My friend David Feldman has insisted that I'm the only person on the planet who worries about issues like these. David certainly has a more realistic view of how the ethical actually plays out, and he tells me that it has sometimes had a negative effect on my (minor) career. But these ethics are part and parcel of the impulse from which I do everything else in my life, my composing most of all. So, if I have erred here in less than diplomatic public utterances, it's a error that I can accept, and if a lack of anonymity in my own opinions has been a career-busting crap shoot, I can always go back to farming.

For example, on the topic of boycotting competitions (in particular, those with high entry fees and low prizes), I have received 22 emails in support of my position and none against, and as gratifying as the echo was, it was a bit disturbing that not one of the 22 was willing to go public. While I might understand it if the emailer doesn't want to be associated in public with me (go google G. Marx on clubs, members, and having me as one), I dislike the idea that he or she doesn't want to upset the competition applecart by speaking out, and profoundly dislike the idea that she or he has chosen anonymity in order to preserve their own competition chances.

I have made a point here of blogging about composers with a diversity of approaches, idioms, and genres, often or even especially those doing work far different from my own. I happen to think that a musical diversity is essential, and I my curiosity about what windband, or choir, or liturgical, or film, or new age, or circuit-bending, or super-complex composers are up to is an honest one. Sometimes, this activity is personally more interesting than activity among musicians with aesthetics closer to my own. (One of my first postings here was about a composer with Asperger's syndrome; his rough approximations of late 18th century music brought out features of that music that I had missed). This has created a few very strong responses and some misunderstandings (I once defended Babbitt's right to compose the music that he wanted and was branded a 12-toner for my defense; unfortunately the brand has lived on in the eternity of internet publication). An anonymous comment recently slammed a composer I mentioned for writing "dreadful pseudo-romantic new age slop". Okay, but why the anonymity? and why not say a bit more about what, precisely, makes it dreadful? I may very well agree with you, but simply dropping a bomb and running away doesn't take us anywhere forward.

Personally, I think that Newmusicland is a microeconomy (or a series of microeconomies within a microeconomy) without much real at stake. Sure, there are prizes to win and teaching gigs to hand out, but in the end, it's a bloody struggle over bloody nothing, or a mad rush for crumbs (thanks to Joyce and Feldman), and even with the "best" resume and connections the distribution of laurels and better day jobs ultimately involves a large factor of the arbitrary. Establishing a public musical identity as a composer means taking a strong position, having strong opinions, and saying through our music in a very public way that I like this and (implicitly) not that. But are our strong opinions only to be placed in public in the form of our music, and not our words? When we switch to words, do we suddenly have a license to duck and cover?

My friend David Feldman has insisted that I'm the only person on the planet who worries about issues like these. David certainly has a more realistic view of how the ethical actually plays out, and he tells me that it has sometimes had a negative effect on my (minor) career. But these ethics are part and parcel of the impulse from which I do everything else in my life, my composing most of all. So, if I have erred here in less than diplomatic public utterances, it's a error that I can accept, and if a lack of anonymity in my own opinions has been a career-busting crap shoot, I can always go back to farming.

Friday, March 23, 2007

Tools

Half the job is finding the right tools. In the kitchen, for example, after 17 years together, we finally have a respectable set of knives, with both the specialty items (filet, tomato, cleaver, and that little knife that curves the wrong way) and the general-purpose (my Wüsthof Classic 8" cook's knife is one of the finest instruments ever made, the Börsendorfer of knives). On my workbench, however, I believe that the search for a good set of clamps is a project for a lifetime.

All the composers I know have been on never-ending searches for the right tools: the right chair, the right desk, a good lamp, the right pen. For a long time, my composing throne of choice was one of a pair of rough palisander straight back chairs from India, but recently and in light of, as Slonimsky put it so well, regressive infantilloquy, I've switched to a fairly ordinary desk chair, treating myself to swivels in any which way, ample padding, arm rests, and those wheels, those wheels.

As far as writing instruments are concerned, I'll admit to a certain amount of infidelity, if not promiscuity. I'm always on the watch for a better pen. I don't use pencils and only use permanent black ink. Before computerized engraving, a pairs of rapidographs and an off-the-shelf calligraphy pen were essential, the rapidographs for lines of different widths and the calligraphy pen for everything else. (I prefer cartridge pens, but some of my colleagues are still dippers or syphoners. For sketching and most other writing, after my teenage flings with the felt-and fine-tipped world, and a collegiate romance with fibre-tips and nylon ball rolling writers, I've had a fairy long partnership with the uni-ball micro, a pen that's gone through a number of manufacturers or distributors, and is now locally allied with Faber-Castell. They do wear out faster than one would like, being surprisingly sensitive to pressure on the ball tip, but I always buy a dozen uni-ball micros at a time, so that a fresh one is always handy. (I've written before about the very useful Noligraph staff writer, another tool no composer should leave home without).

One last note to the loved ones and acquaintances of composers: if you're looking for the perfect gift for a composer, you can forget the tie, but we do actually look favorably on the right writing instruments.

All the composers I know have been on never-ending searches for the right tools: the right chair, the right desk, a good lamp, the right pen. For a long time, my composing throne of choice was one of a pair of rough palisander straight back chairs from India, but recently and in light of, as Slonimsky put it so well, regressive infantilloquy, I've switched to a fairly ordinary desk chair, treating myself to swivels in any which way, ample padding, arm rests, and those wheels, those wheels.

As far as writing instruments are concerned, I'll admit to a certain amount of infidelity, if not promiscuity. I'm always on the watch for a better pen. I don't use pencils and only use permanent black ink. Before computerized engraving, a pairs of rapidographs and an off-the-shelf calligraphy pen were essential, the rapidographs for lines of different widths and the calligraphy pen for everything else. (I prefer cartridge pens, but some of my colleagues are still dippers or syphoners. For sketching and most other writing, after my teenage flings with the felt-and fine-tipped world, and a collegiate romance with fibre-tips and nylon ball rolling writers, I've had a fairy long partnership with the uni-ball micro, a pen that's gone through a number of manufacturers or distributors, and is now locally allied with Faber-Castell. They do wear out faster than one would like, being surprisingly sensitive to pressure on the ball tip, but I always buy a dozen uni-ball micros at a time, so that a fresh one is always handy. (I've written before about the very useful Noligraph staff writer, another tool no composer should leave home without).

One last note to the loved ones and acquaintances of composers: if you're looking for the perfect gift for a composer, you can forget the tie, but we do actually look favorably on the right writing instruments.

Thursday, March 22, 2007

Not knowing much

Alex Ross has been investigating the classical music sales numbers racket. As might have been expected, it's a story of niche markets within niche markets. Classical music (and, we may presume, new music) is not a game that is played only by a small set of major players. Instead, the sources and marketplaces are many and widely distributed (often off-shore). Sales figures are often a carefully constructed fiction, a balancing act between suggesting, to the public, great success and admitting, to tax authorities and creditors, great failures. There simply aren't the large sales numbers from a few well-known market-leading products required to create the kind of stable, reliable, and meaningful numbers required to generate useful statistics. Moreover, there is some evidence that classical music has a long tail effect and is difficult to compass in terms of seasonal or annual sales. We do know that the market is small, relative to the bigger pop markets. We know that many - if not most - participants have to be producing recordings for reasons other than significant income production. But we also know that the market must be large and profitable enough in some niches that some small number of people actually earns money from it. But in sum, we don't know much and our predictive power is limited.

Part of the problem is that once commodified, any music has some potential to cross into other markets -- Frank J. Oteri has noted the presence of some Indian classical music recording in a recent 1001 list; Oteri was concerned about the absence of classical music from the list, but those Indian classical recordings (Hindustani repertoire from artists with reputations acquired from association with western pop musicians) entered the list as a form of western pop musics, not as Indian classical music. (In India itself, classical music recordings are also a microscopic part of the music market which is dominated by the local popular and film music genres. It is fascinating, by the way, to listen to pop music in a country like Indonesia, where western and Indian pop musics are relatively equal in popularity, despite any marketing advantages western products may have).

The brightest perspectives, methinks, for recordings of new and experimental music, lay in two directions. On the one hand, there are cross market and long tail effects, in which, in the past, a Beatles listener might get hooked on Indian classical music via curiosity in the music that got George Harrison so excited. Today, I am told by a friend with expertise in both pop and new music, someone who likes The Arcade Fire may go on to Owen Pallett and then on to Corey Dargel (I don't know any of this music) and pretty soon she or he has landed in one neighborhood of Newmusicland. But that strikes me as relying on an arbitrary and unpredictable chain of connections, and risks Pop's version of the Kronos mechanism (Kronos ate his children, pop music eats its children, as well as its cousins, ancestors, and neighbors). On the other hand, new musicians have an expertise in maneuvering on the margins and within a niche, and all signs of the market for recordings to come, point to one that is increasingly uncentered and niche-oriented. This is a phenomena that scares the bejeezus out of the big pop record companies, and they're scrambling to assert rights and privileges in a market that is increasingly resistant to their old bag of tricks and charms. So, and writing only as someone who doesn't really do recordings and will readily admit to not knowing much, perhaps there's an opening here, and relative obscurity can be turned into useful experience.

Part of the problem is that once commodified, any music has some potential to cross into other markets -- Frank J. Oteri has noted the presence of some Indian classical music recording in a recent 1001 list; Oteri was concerned about the absence of classical music from the list, but those Indian classical recordings (Hindustani repertoire from artists with reputations acquired from association with western pop musicians) entered the list as a form of western pop musics, not as Indian classical music. (In India itself, classical music recordings are also a microscopic part of the music market which is dominated by the local popular and film music genres. It is fascinating, by the way, to listen to pop music in a country like Indonesia, where western and Indian pop musics are relatively equal in popularity, despite any marketing advantages western products may have).

The brightest perspectives, methinks, for recordings of new and experimental music, lay in two directions. On the one hand, there are cross market and long tail effects, in which, in the past, a Beatles listener might get hooked on Indian classical music via curiosity in the music that got George Harrison so excited. Today, I am told by a friend with expertise in both pop and new music, someone who likes The Arcade Fire may go on to Owen Pallett and then on to Corey Dargel (I don't know any of this music) and pretty soon she or he has landed in one neighborhood of Newmusicland. But that strikes me as relying on an arbitrary and unpredictable chain of connections, and risks Pop's version of the Kronos mechanism (Kronos ate his children, pop music eats its children, as well as its cousins, ancestors, and neighbors). On the other hand, new musicians have an expertise in maneuvering on the margins and within a niche, and all signs of the market for recordings to come, point to one that is increasingly uncentered and niche-oriented. This is a phenomena that scares the bejeezus out of the big pop record companies, and they're scrambling to assert rights and privileges in a market that is increasingly resistant to their old bag of tricks and charms. So, and writing only as someone who doesn't really do recordings and will readily admit to not knowing much, perhaps there's an opening here, and relative obscurity can be turned into useful experience.

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

Filling the Cartesian Lacuna

Paul Bailey has begun a small history of the complex of Southern Californian composer-led ensembles which begins with the legendary Cartesian Reunion Memorial Orchestra. (If you visit that page, have a listen to Douglas Hein's Orlando, He Dead and Lloyd Rodger's Message for Garcia).

Although Bailey has emphasized the "say little, do much" posture, it would be cool if someone could find the time to write something more about the musical and social ideas underlying the work. At first hearing, much of the music of the Cartesians and the various post-Cartesians suggests a spirit more kindred with some English minimalists (Bryars, Hobbs, Nyman et al) than with their better-known US colleagues, however, these musicians definitely have an attitude that is uniquely their own, and I'm especially taken with their detournements of musical history from the ground bass to the Lugubrious Gondola, and -- pace Heins -- from di Lasso to Mama Cass.

Also, as someone coming from my own odd corner of SoCal, I can't emphasize enough that the Cartesians and the bands in their wake did not spring from the center of LA or from any of the influential institutional bases. On the one hand, this is a healthy phenomenon, and shows that neither the LA Phil, USC, Hollywood, or Cal Arts has a monopoly on creative music making, but on the other hand, it's impossible to get away from the downside in which working away from those institutions can leave one quite isolated from the networks of grant-giving, residencies, award-giving, and access to media. It's really one thing to say that you come from CalArts and are therefore an "alternative artist", but quite another to say that if you come from Fullerton or Redlands or Mt. Baldy Village.

Although Bailey has emphasized the "say little, do much" posture, it would be cool if someone could find the time to write something more about the musical and social ideas underlying the work. At first hearing, much of the music of the Cartesians and the various post-Cartesians suggests a spirit more kindred with some English minimalists (Bryars, Hobbs, Nyman et al) than with their better-known US colleagues, however, these musicians definitely have an attitude that is uniquely their own, and I'm especially taken with their detournements of musical history from the ground bass to the Lugubrious Gondola, and -- pace Heins -- from di Lasso to Mama Cass.

Also, as someone coming from my own odd corner of SoCal, I can't emphasize enough that the Cartesians and the bands in their wake did not spring from the center of LA or from any of the influential institutional bases. On the one hand, this is a healthy phenomenon, and shows that neither the LA Phil, USC, Hollywood, or Cal Arts has a monopoly on creative music making, but on the other hand, it's impossible to get away from the downside in which working away from those institutions can leave one quite isolated from the networks of grant-giving, residencies, award-giving, and access to media. It's really one thing to say that you come from CalArts and are therefore an "alternative artist", but quite another to say that if you come from Fullerton or Redlands or Mt. Baldy Village.

Monday, March 19, 2007

Notes on Continuity

I'm drawn to two extremes, as separate as continents, of musical continuity. One is smooth and seamless, unrelenting in its progress, and the other moves in fits and starts, interrupted by new ideas, or broken by silences as much as by noises.

*****

Some musicians hear music as lines, but some lines are full and others dotted, branched, or even broken.

*****

Traditional forms, whether song or dance in origin, derived continuity from rhythmic movement, on the one hand, and tonal expansion and closure on the other, and combined the two in the form of the cadence, which in essence was a signal that the continuity, the movement, was over.

*****

Traditional continuity was challenged in two ways, first through backgrounding the continuity, in a figure and ground arrangement (c.f. the second movement, "Szene am Bach", of the Pastorale Symphony), and second through making continuity out of continuous change (Brahms' "developing variations") or of continuously refreshing a small set of source materials, as in the fugue.

*****

Christian Wolff's essay On Form in die Reihe: a shattering experience, redefining the extent of a piece as the time available in a program, and continuity within a piece reheard simply as a sequence of events, adjunct, overlapping, or separated by silences. The system of cued continuities used in many of Wolff's scores shows how rich this terrain might be (John Zorn's game pieces were related).

James Tenney's Meta+Hodos introduced the terms of cohesion and segregation, useful notions in characterizing the relationships between materials, whether successive or simultaneous. (Ezra Pound's little book George Antheil & The Theory of Harmony described an economic relationship between the distances among sounds in terms of time and type; late in his life, John Cage would advocate an ecological balance among sounds based upon loudness: when quiet, any sound could follow an other, but louder sounds required greater separation in time).

*****

The form of much electronic music has been based upon a substitution of the basic binary nature of a circuit -- either on or off -- for the system of movement and cadence. The tendency of pieces of electronic music to fill their entire durations with sound is a pronounced one, from La Monte Young Dream House to Douglas Leedy's Entropical Paradise to the convivial worlds of house and techno; examples in which electronic music has turned toward a more broken continuity, via a more frequent use of the switch (my favorite is Gordon Mumma's Pontpoint with its rich islands of sonority divided by oceans of silence), are rare but rich.

*****

Always keep your ears out for a reconciliation of opposites. The experimental music important to my musical youth included both the broken continuity heard in some of Cage's or Christian Wolff's music and the breathtakingly non-stop continuity of 60's/70's minimalism. Bridging the two continents seemed an essential and urgent task, but solutions were rare. Jo Kondo's music offered one solution; its mixture of tonal ambiguity and quasi-repetition created an environment in which everything heard was recognizably a part of a whole, yet it was seldom certain why this should be precisely so.

*****

In my imagination, the minimalism of my youth shares a compartment with a few pieces of extraordinary film-making. One of these is that magnificent last shot in Antonioni's The Passenger. A single non-stop camera shot that moves up and out of a room, through (how?) a barred window and onto the dusty street, while the "action" takes place, audibly only, and off and presumably behind the camera, in the it has left. Absolute continuity and a eventful narrative are placed in counterpoint by the severance of sight from sound. Another is Claude Lelouch's legendary C'était un Rendezvous, a high-speed race (probably in a Ferrari 275 GTB) through Paris in early morning light, an uncut single-reel shot, in which the continuity is continuous broken by details -- the scenery, the changing noise of the transmission, the sudden appearances of pedestrians rushing for dear life away from the on-coming traffic offender, and the shockingly neat finale which gives the film its name (again, how was that done?). Both of these bits of camera work have an odd effect on the viewer in that we become separate ourselves so comfortably into schizophrenic halves, one of whom is intensely aware of the technical achievement, and the other of whom is fully lost to the moving image and its wealth of details.

The connection here is to the music of Young, Riley, Glass, Reich, and others in which our attentions drifted inevitably to the complex and unpredictable acoustic graffiti or halo of combination effects while the actual physical "notes" played on instruments or sung by voices -- which were not necessarily interesting in their own rights -- vanished below the threshold of attention. (A friend pointed to a funny moment in a recent online interview with the composer Nico Muhly in which he talks of this music being "about maths" but still being heard with an emotional charge (excuse my paraphrase if I got it wrong) -- but it was never "about maths" in the first place but always rather about the potential of music to go beyond a reduction to maths, and the composer's task was to locate musical scenaria in which this potential would be realized in a clear and vivid way. )

*****

Some musicians hear music as lines, but some lines are full and others dotted, branched, or even broken.

*****

Traditional forms, whether song or dance in origin, derived continuity from rhythmic movement, on the one hand, and tonal expansion and closure on the other, and combined the two in the form of the cadence, which in essence was a signal that the continuity, the movement, was over.

*****

Traditional continuity was challenged in two ways, first through backgrounding the continuity, in a figure and ground arrangement (c.f. the second movement, "Szene am Bach", of the Pastorale Symphony), and second through making continuity out of continuous change (Brahms' "developing variations") or of continuously refreshing a small set of source materials, as in the fugue.

*****

Christian Wolff's essay On Form in die Reihe: a shattering experience, redefining the extent of a piece as the time available in a program, and continuity within a piece reheard simply as a sequence of events, adjunct, overlapping, or separated by silences. The system of cued continuities used in many of Wolff's scores shows how rich this terrain might be (John Zorn's game pieces were related).

James Tenney's Meta+Hodos introduced the terms of cohesion and segregation, useful notions in characterizing the relationships between materials, whether successive or simultaneous. (Ezra Pound's little book George Antheil & The Theory of Harmony described an economic relationship between the distances among sounds in terms of time and type; late in his life, John Cage would advocate an ecological balance among sounds based upon loudness: when quiet, any sound could follow an other, but louder sounds required greater separation in time).

*****

The form of much electronic music has been based upon a substitution of the basic binary nature of a circuit -- either on or off -- for the system of movement and cadence. The tendency of pieces of electronic music to fill their entire durations with sound is a pronounced one, from La Monte Young Dream House to Douglas Leedy's Entropical Paradise to the convivial worlds of house and techno; examples in which electronic music has turned toward a more broken continuity, via a more frequent use of the switch (my favorite is Gordon Mumma's Pontpoint with its rich islands of sonority divided by oceans of silence), are rare but rich.

*****

Always keep your ears out for a reconciliation of opposites. The experimental music important to my musical youth included both the broken continuity heard in some of Cage's or Christian Wolff's music and the breathtakingly non-stop continuity of 60's/70's minimalism. Bridging the two continents seemed an essential and urgent task, but solutions were rare. Jo Kondo's music offered one solution; its mixture of tonal ambiguity and quasi-repetition created an environment in which everything heard was recognizably a part of a whole, yet it was seldom certain why this should be precisely so.

*****

In my imagination, the minimalism of my youth shares a compartment with a few pieces of extraordinary film-making. One of these is that magnificent last shot in Antonioni's The Passenger. A single non-stop camera shot that moves up and out of a room, through (how?) a barred window and onto the dusty street, while the "action" takes place, audibly only, and off and presumably behind the camera, in the it has left. Absolute continuity and a eventful narrative are placed in counterpoint by the severance of sight from sound. Another is Claude Lelouch's legendary C'était un Rendezvous, a high-speed race (probably in a Ferrari 275 GTB) through Paris in early morning light, an uncut single-reel shot, in which the continuity is continuous broken by details -- the scenery, the changing noise of the transmission, the sudden appearances of pedestrians rushing for dear life away from the on-coming traffic offender, and the shockingly neat finale which gives the film its name (again, how was that done?). Both of these bits of camera work have an odd effect on the viewer in that we become separate ourselves so comfortably into schizophrenic halves, one of whom is intensely aware of the technical achievement, and the other of whom is fully lost to the moving image and its wealth of details.

The connection here is to the music of Young, Riley, Glass, Reich, and others in which our attentions drifted inevitably to the complex and unpredictable acoustic graffiti or halo of combination effects while the actual physical "notes" played on instruments or sung by voices -- which were not necessarily interesting in their own rights -- vanished below the threshold of attention. (A friend pointed to a funny moment in a recent online interview with the composer Nico Muhly in which he talks of this music being "about maths" but still being heard with an emotional charge (excuse my paraphrase if I got it wrong) -- but it was never "about maths" in the first place but always rather about the potential of music to go beyond a reduction to maths, and the composer's task was to locate musical scenaria in which this potential would be realized in a clear and vivid way. )

Sunday, March 18, 2007

Terminological drift

The BBC news has a report that "boys tend not to join choirs because they think their singing voices "do not sound like boys", with the "sound of boys" now understood to be that produced by young men who sing in "boy bands". The name "boy bands" already contained some some substantial redefinition in that the proper membership of these groups were not instrumentalists, but rather singers, continuing the tendency long present in pop music in which singers were more fully integrated into "the band", as opposed to the traditional separation of instrumental and vocal forces (orchestra/choir, big band/singers, etc.).

(There is also a popular redefinition in which music is no longer made/written/composed by a composer or even a songwriter, but rather by a band; radio announcers seldom indicate the specific authors, and a great number of listeners can readily ID the band in question but not the individual composers.)

There is a real knot of gender and mass culture issues involved here which are well beyond my sphere of knowledge and , to be honest, interest, but will note that some of the childrens' choirs I heard in Hungary, with both boys and girls in the ensemble, were remarkable, achieving musical results with - to my ears - sophistication well beyond that of the best-known German-speaking or English Boys' choirs. (I say it's aspinach childrens' choir, and I say to hell with it!).

(There is also a popular redefinition in which music is no longer made/written/composed by a composer or even a songwriter, but rather by a band; radio announcers seldom indicate the specific authors, and a great number of listeners can readily ID the band in question but not the individual composers.)

There is a real knot of gender and mass culture issues involved here which are well beyond my sphere of knowledge and , to be honest, interest, but will note that some of the childrens' choirs I heard in Hungary, with both boys and girls in the ensemble, were remarkable, achieving musical results with - to my ears - sophistication well beyond that of the best-known German-speaking or English Boys' choirs. (I say it's a

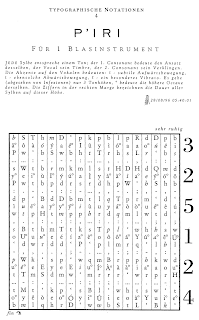

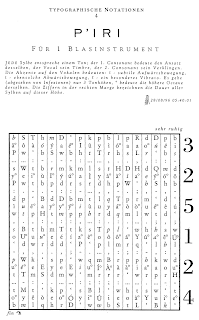

Typographic Notation

Here are two examples of typographic notation, in scores by Danyel Franke. These scores are both demanding and great fun to play as they are, on first impression, quite open, but reveal themselves, when played with discipline, consistency, and logical consequence, as well-defined musical environments. Among the elements that Franke brings to his scores are East Asian court and scholarly music, the music of Feldman (and to some extent, Cage), and simultaneous engagements with literary culture and musical improvisation. (Any errors in the translations are mine). Franke writes about these pieces:

(ABSTRACT COMPOSITION IV, for 4-6 archaic instruments. Each sign indicates one tone (an empty field indicates a rest); all players read from the same part, each for themself; one begins in an arbitrary field & moves further to a neighboring field. Four letters from the Kufi alphabet indicate four pitches, the more clear the pitches of an instrument are, the more narrow the intervals should be between them; when a player crosses a double line, one of the four pitches is changed. The numbers in the right-hand margin indicate the durations for all fields in the row.)

(P'IRI for one wind instrument. Each syllable comprises one tone; the first consonant indicates the attack of the tone, the vowel idicates the timbre, and the second consonant the release. The accents over the vowels indicate: í - a subtle upwart movement, ì - a similarly subtle downward movement, and î - a certain vibrato. There are (independent from inflections) only three pitches, with ° indicating these pitches one octave higher. The numbers in the right-hand margin indicate the duration of all syllables in the row.)

... two specimens, one (P'iri) (is) rather demanding and shows the use of typographic notation for qualities of performance normally not notated, while the other (# IV) is quite plain and we used to play it on picnics at the time. It shows the use of letter notation (related to Javanese notation) for pitches or, rather, scale degrees (actually derived from the early Arab theorists who inherited it from the Greek), but using it for variable, indeterminate scales. Use of numerals to indicate duration is found in Arab notation from the 13th c.

(ABSTRACT COMPOSITION IV, for 4-6 archaic instruments. Each sign indicates one tone (an empty field indicates a rest); all players read from the same part, each for themself; one begins in an arbitrary field & moves further to a neighboring field. Four letters from the Kufi alphabet indicate four pitches, the more clear the pitches of an instrument are, the more narrow the intervals should be between them; when a player crosses a double line, one of the four pitches is changed. The numbers in the right-hand margin indicate the durations for all fields in the row.)

(P'IRI for one wind instrument. Each syllable comprises one tone; the first consonant indicates the attack of the tone, the vowel idicates the timbre, and the second consonant the release. The accents over the vowels indicate: í - a subtle upwart movement, ì - a similarly subtle downward movement, and î - a certain vibrato. There are (independent from inflections) only three pitches, with ° indicating these pitches one octave higher. The numbers in the right-hand margin indicate the duration of all syllables in the row.)

More radical than me

Composer William Houston has this message on his website:

"Although I have decided to at least temporarily continue to make my music available, I am entirely finished with the music establishment. No mainstream American music institution will be permitted to perform my work (Not that there's much chance of it anyway). Why? Because it's a rigged game and because it's run by the elite; the same people who profit from dead Iraqi women and children. Some of the same people who stage terror attacks. Am I saying that, for instance, Esa-Pekka Solonen is a terrorist? No, but I am saying he works for terrorists, among others. I don't want that job."

Saturday, March 17, 2007

Who's counting?

Some housekeeping:

For the past year or so, I've had a Site Meter counter and a link to Who Links to Me on this blog. For one reason or another, both have been going haywire of late, sometimes even dropping off the face of the blogoplan. That's annoying, but not as annoying as the fact that I was getting concerned about it, and worrying about visitor counters and counts of vistors was definitely not in the spirit of this enterprise. So, the counters are gone, goodbye, aloha, ciao, tchuss, szia, sugeng kondur, good riddance, and later dates, dudes...

The blogroll continues to beg for maintenance. What is the etiquette of blogrolls, anyways? Is mutual blogrolling ("I'll blogroll you if you blogroll me") the order of the day?* Or should I only blogroll the pages I actually return to often? I've already committed myself to not blogrolling the institutional bloggers (NYTimes, ArtsJournal, Guardian), and I've been hesitant to include the non-musical pages I like, but that point is negotiable.

_____

* Mutual blogrolling has a slightly off-color feel, somewhat like self-googling, an activity in which everyone engages, but to which no one admits. But unlike self-googling, which is harmless, mutual blogrolling has the potential, like mutual citations in academic papers, to inflate the relevance and inportance of the references.

For the past year or so, I've had a Site Meter counter and a link to Who Links to Me on this blog. For one reason or another, both have been going haywire of late, sometimes even dropping off the face of the blogoplan. That's annoying, but not as annoying as the fact that I was getting concerned about it, and worrying about visitor counters and counts of vistors was definitely not in the spirit of this enterprise. So, the counters are gone, goodbye, aloha, ciao, tchuss, szia, sugeng kondur, good riddance, and later dates, dudes...

The blogroll continues to beg for maintenance. What is the etiquette of blogrolls, anyways? Is mutual blogrolling ("I'll blogroll you if you blogroll me") the order of the day?* Or should I only blogroll the pages I actually return to often? I've already committed myself to not blogrolling the institutional bloggers (NYTimes, ArtsJournal, Guardian), and I've been hesitant to include the non-musical pages I like, but that point is negotiable.

_____

* Mutual blogrolling has a slightly off-color feel, somewhat like self-googling, an activity in which everyone engages, but to which no one admits. But unlike self-googling, which is harmless, mutual blogrolling has the potential, like mutual citations in academic papers, to inflate the relevance and inportance of the references.

Everyone loves a mystery

One short follow-up to the previous post about The Boring Store writing program:

Perhaps instead of emphasizing the niche-ness of new and experimental music, we should emphasize its hiddenness; its mysterious and (quite literally) apocalyptic qualities. This is music that doesn't fit into the conventions of plain-vanilla everyday institutional music-making, and indeed, this is the music that those institutions would rather have quietly go away. There is plenty of music that is readily available in the marketplace and readily accessible in musical character, but does it have the depth to reward returning to it again and again? Will re-investigations of the music reveal anything new or pose new questions about sound, music, or the world around that music? A new and non-commercial music is never going to compete in the mass marketplace with the brilliant veneer of institutional pop or classical music, but it has potential to engage the throughtful and imaginative in ways in which the mass products cannot afford or sustain.

(BTW: Here's a site with a few audio files from the I Love A Mystery radio series).

Perhaps instead of emphasizing the niche-ness of new and experimental music, we should emphasize its hiddenness; its mysterious and (quite literally) apocalyptic qualities. This is music that doesn't fit into the conventions of plain-vanilla everyday institutional music-making, and indeed, this is the music that those institutions would rather have quietly go away. There is plenty of music that is readily available in the marketplace and readily accessible in musical character, but does it have the depth to reward returning to it again and again? Will re-investigations of the music reveal anything new or pose new questions about sound, music, or the world around that music? A new and non-commercial music is never going to compete in the mass marketplace with the brilliant veneer of institutional pop or classical music, but it has potential to engage the throughtful and imaginative in ways in which the mass products cannot afford or sustain.

(BTW: Here's a site with a few audio files from the I Love A Mystery radio series).

Luring them in

Here's a great photo guide to The Boring Store, part of author Dave Eggars' chain of free writing programs for urban young people. Disguised by a store front advertising itself as most definitely not a place to buy spy and secret agent supplies, The Boring Store is actually a cover for a creative writing workshop, with the false front the perfect way for drawing young people in.

As someone who both loved and loathed the band- and choir-based mass music education system in US schools (Paul Bailey recently had a post on a similar topic), I'm always on the lookout for alternative and complementary approaches, and in particular, those alternatives which lead to a broader idea of what music is and might be. (Have no doubt, the present conservatism is due in large part to the built-in resilience of institutional music instruction in the US). I could well imagine a curious storefront similar to that of The Boring Store, hiding a workshop for both getting to know new music and making some of it yourself, through composition and improvisation, with tools and materials for instrument building and some basic sound recording and editing equipment.

As someone who both loved and loathed the band- and choir-based mass music education system in US schools (Paul Bailey recently had a post on a similar topic), I'm always on the lookout for alternative and complementary approaches, and in particular, those alternatives which lead to a broader idea of what music is and might be. (Have no doubt, the present conservatism is due in large part to the built-in resilience of institutional music instruction in the US). I could well imagine a curious storefront similar to that of The Boring Store, hiding a workshop for both getting to know new music and making some of it yourself, through composition and improvisation, with tools and materials for instrument building and some basic sound recording and editing equipment.

Friday, March 16, 2007

Construction

In an item in Lou Harrison's Music Primer, Harrison describes the "tune kit" from which the odd-numbered movements of his Pacifika Rondo were composed. He used the permutations of a set of numbers (for example: {2,3,5,6}) to determine the lengths of successive measures within a phrase, and then started applying accents, ornaments, inserting rests and additional tones, etc., with each addition procedure introduced at positions fixed by alternative permutations of the numbers within the phrase. Explained in inimitably clear Harrisonian fashion, here was a rich way of organizing and generating variety from a very small set of materials.

I was given a copy of the Music Primer in High School, and it's been a constant source of ideas and enthusiasm for my own musical experiments. Many years later, in a Darmstadt chalk talk, I watched Brian Ferneyhough demonstrate a procedure that was, at root, essentially the same as that used by Harrison, but used by Ferneyhough to a vastly different effect. Harrison's music in Pacifika Rondo was modal and monophonic, with some simultaneous variations on the trunk melody within the ensemble, an hommage to East Asian court music traditions with a quirky but coherent formal and rhythmic spin. The application of the various layers of procedures added detail and drive, but the whole retained a unified and lyrical character. Ferneyhough's example sounded totally unlike Harrison's, due first to a more unruly choice of materials, and then his even more densely layered use of the procedures could be said to have had the tendency to break-up, or even make polyphonic, rather than to unify. These two examples demonstrate how a choice of materials, and the aesthetic governing their application can trump similarities in method.

This example of a convergence of methods and divergent musical results may be a useful counter to the complaints that modern music has been over-obsessed with its construction. (The extreme of this idea is the notion that describing how a piece was made will be an adequate and sufficient account of the work). To the contrary, I think most composers are well aware of both the utility and limits of their methods, and particularly the role of personal taste and style in realizing the potential of a given method. If our talk about music seems dominated by talk of method, it's not because any particular importance is to be located in a particular method, but simply because it's something that can be talked about. On the other hand, while music of any sort may have the power to invoke speechlessness, the absence of talk around a music, be it talk about its construction, reception, or context may be strongly suggestive that the absences are more than just talk.

Harrison found a real richness and balance in his best music (he was a marvelously uneven composer!), which is at once complex in its construction and web of external references and immediate in its reception. Other musics, like that of Ferneyhough, have found and will find other ways of locating and balancing these elements.

I was given a copy of the Music Primer in High School, and it's been a constant source of ideas and enthusiasm for my own musical experiments. Many years later, in a Darmstadt chalk talk, I watched Brian Ferneyhough demonstrate a procedure that was, at root, essentially the same as that used by Harrison, but used by Ferneyhough to a vastly different effect. Harrison's music in Pacifika Rondo was modal and monophonic, with some simultaneous variations on the trunk melody within the ensemble, an hommage to East Asian court music traditions with a quirky but coherent formal and rhythmic spin. The application of the various layers of procedures added detail and drive, but the whole retained a unified and lyrical character. Ferneyhough's example sounded totally unlike Harrison's, due first to a more unruly choice of materials, and then his even more densely layered use of the procedures could be said to have had the tendency to break-up, or even make polyphonic, rather than to unify. These two examples demonstrate how a choice of materials, and the aesthetic governing their application can trump similarities in method.

This example of a convergence of methods and divergent musical results may be a useful counter to the complaints that modern music has been over-obsessed with its construction. (The extreme of this idea is the notion that describing how a piece was made will be an adequate and sufficient account of the work). To the contrary, I think most composers are well aware of both the utility and limits of their methods, and particularly the role of personal taste and style in realizing the potential of a given method. If our talk about music seems dominated by talk of method, it's not because any particular importance is to be located in a particular method, but simply because it's something that can be talked about. On the other hand, while music of any sort may have the power to invoke speechlessness, the absence of talk around a music, be it talk about its construction, reception, or context may be strongly suggestive that the absences are more than just talk.

Harrison found a real richness and balance in his best music (he was a marvelously uneven composer!), which is at once complex in its construction and web of external references and immediate in its reception. Other musics, like that of Ferneyhough, have found and will find other ways of locating and balancing these elements.

Thursday, March 15, 2007

You can't do this here

(An encore posting from 25 July 2006)

I read through the score of Stravinsky's Movements this morning, a favorite piece* and realized that the old man does a lot of things younger composers can't get away with anymore in the American concert hall, between sharp breaks in continuity and a steadfast anti-tonality.

Tragic but true: when the smoke had cleared, the new music wars had been won not by towners up or down or coasters east or left, but by a rear guard of trained symphonic band composers from big state universities in the middle of the country. The surviving rebels were exiled, retrained, or forced into dayjobs in data processing and direct telephone sales.

_____

* One thing I like about Movements: It positively resists ending the analysis with a description of the technique used for selecting the pitches**. Listening closely suggests connections to other musics, including some musics which share no technical means with Stravinsky's , and even musics with which the composer was presumably unfamiliar, from the Ars Subtilor to the cuing pieces by Christian Wolff. Like late 14th century music, Movements has a tonal environment in which mo(ve)ments dominated by acoustic consonances border directly with mo(ve)ments that resist the ear's favor, and those borders give the music part of it's quirky, crispy character. Like the Wolff pieces, Movements is composed of fragments, pushing our ears to follow successions of continuities, sharp cuts, and simultaneities which cohere only with great uncertainty. And the music flies by -- the grace note (Stravinsky had always been a grace note consumer, but the influence of Webern's grace notes plays a role here, too) has been elevated to a basic pulse, or rather a basic presence, its duration removed or stolen from metrical time. (In Wolff's cuing pieces, the use of a "zero" time unites both the stolen time of the grace note with the non-metrical time of caesuras, fermatas, and the outside-of-the-movement time between movements; Nono's late, great string quartet would later use a scale of fermatas). This music is quite literally composed of a series of contrasting movements, with distinct tempi and rhythmic profiles, sometime reappearing, sometimes disappearing (a pre-emptive challenge to Stockhausen's notion of a "moment form"?) But in the end, the old craftsman Stravinsky knows that the fragments are defined as much by the places where the join, or playfully fail to join, as by their own substance. In fact, there is something random-sounding about the details here -- Stravinsky grabbed from his "verticalized" row-charts in very much the same spirit in which Wolff invites his players to select from pools of pitches here and there on the score -- but it's entirely in keeping with the composer's wisdom that constrast and complementarity need not be understood immediately and in detail, but can be discerned in an impressionistic way.

**Descriptions of the sort can be found in all of the usual places by all of the usual suspects, among whom Josef Straus is particularly, if not unusually, good.

I read through the score of Stravinsky's Movements this morning, a favorite piece* and realized that the old man does a lot of things younger composers can't get away with anymore in the American concert hall, between sharp breaks in continuity and a steadfast anti-tonality.

Tragic but true: when the smoke had cleared, the new music wars had been won not by towners up or down or coasters east or left, but by a rear guard of trained symphonic band composers from big state universities in the middle of the country. The surviving rebels were exiled, retrained, or forced into dayjobs in data processing and direct telephone sales.

_____

* One thing I like about Movements: It positively resists ending the analysis with a description of the technique used for selecting the pitches**. Listening closely suggests connections to other musics, including some musics which share no technical means with Stravinsky's , and even musics with which the composer was presumably unfamiliar, from the Ars Subtilor to the cuing pieces by Christian Wolff. Like late 14th century music, Movements has a tonal environment in which mo(ve)ments dominated by acoustic consonances border directly with mo(ve)ments that resist the ear's favor, and those borders give the music part of it's quirky, crispy character. Like the Wolff pieces, Movements is composed of fragments, pushing our ears to follow successions of continuities, sharp cuts, and simultaneities which cohere only with great uncertainty. And the music flies by -- the grace note (Stravinsky had always been a grace note consumer, but the influence of Webern's grace notes plays a role here, too) has been elevated to a basic pulse, or rather a basic presence, its duration removed or stolen from metrical time. (In Wolff's cuing pieces, the use of a "zero" time unites both the stolen time of the grace note with the non-metrical time of caesuras, fermatas, and the outside-of-the-movement time between movements; Nono's late, great string quartet would later use a scale of fermatas). This music is quite literally composed of a series of contrasting movements, with distinct tempi and rhythmic profiles, sometime reappearing, sometimes disappearing (a pre-emptive challenge to Stockhausen's notion of a "moment form"?) But in the end, the old craftsman Stravinsky knows that the fragments are defined as much by the places where the join, or playfully fail to join, as by their own substance. In fact, there is something random-sounding about the details here -- Stravinsky grabbed from his "verticalized" row-charts in very much the same spirit in which Wolff invites his players to select from pools of pitches here and there on the score -- but it's entirely in keeping with the composer's wisdom that constrast and complementarity need not be understood immediately and in detail, but can be discerned in an impressionistic way.

**Descriptions of the sort can be found in all of the usual places by all of the usual suspects, among whom Josef Straus is particularly, if not unusually, good.

Wednesday, March 14, 2007

Study Scores, again

Steve Hicken of the excellent blog listen. has weighed in to echo the call made here for free online study scores. Again, this is not something that will cost publishers money in the long run, but rather aid in the promotion of performances and mechanicals through ensuring that the scores remain present in the larger musical culture.

What is the best way to go forward with a lobbying effort for this? Should individual publishers be contacted, or should composer, performers, and academics make a group request?

What is the best way to go forward with a lobbying effort for this? Should individual publishers be contacted, or should composer, performers, and academics make a group request?

Lost and Found

Look for one thing, find another. Searching for some old letters, I wound up in a stack of old sketches and scores, discovering a half-dozen pieces that I had completely forgotten, and now can hardly imagine having written. At least one of them was 30 (!) years old, a violin and piano piece, with a title as pretentious as only a fifteen-year-old can manage, Palinode. What kind of music was this? It's not tonal, three minutes long, covers the entire range of each instrument (lots of ledger lines), has constantly changing dynamics and tempi, and comed across as much bigger and more serious than it ought to be, an belated entry into the big-a atonal bebop sweepstakes. The method of composition - and I suspect that there was one - is totally opaque, not to be reconstructed. In other words, it does all of the things I've since learned that I either should not or do not want to do (nowadays, more than four ledger lines invokes vertigo). What kind of person would have made this? I recognize him even less than I do the score, and though the musical sensibility audible in the notes is not yet well-formed, I'd sure like to recover some of that naivete, that fearlessness.

Monday, March 12, 2007

E-Commission Pioneer

Composer Celeste Hutchins is offering all of us the possibility to join the ranks of the patrons of the arts by commissioning some new works at a very reasonable price. As far as I know, Hutchins is the first composer to do commission billing via PayPay.

____

Update: I've since heard from a few other composers who have used PayPal for commissions, but Hutchins has got a PayPal button on her blog, so that the payment can be done without an exchange of emails. (I should note that I don't use PayPal myself, as PayPal does a number of banking functions, indeed earns its money on transaction and exchange rate margins, without being held to banking regulations).

____

Update: I've since heard from a few other composers who have used PayPal for commissions, but Hutchins has got a PayPal button on her blog, so that the payment can be done without an exchange of emails. (I should note that I don't use PayPal myself, as PayPal does a number of banking functions, indeed earns its money on transaction and exchange rate margins, without being held to banking regulations).

Cage in Iran

With the news that works by John Cage have been programmed in Tehran, it's perhaps worth pointing out that while these performances are probably the first of Cage's work since the revolution, they are not the first performances of Cage's music in Iran: the Cunningham Dance Company, with Cage as music director, toured Iran in 1972.

Off the clock

Roger Bourland has a nice post about students and early class hours. My entire freshman year in college featured a 7:45 theory and musicianship course every day from Monday through Friday. By the second quarter of the year I had figured out that I could only meet that class if I had stayed up the whole night before, treating the class as the end of graveyard shift, sleeping a bit afterwards, and scheduling the rest of my classes for the late afternoon. In practice, I just didn't sleep much, and being young and indestructable, didn't much mind it at the time. (Some friends used to joke that I was far too evil to rest. You can judge for yourself).

Musicians -- who concertize in the evening -- are generally at a time-shift to the rest of the working population. I've got both that shift and a stubborn disinclination to ever shift out of Pacific Coast time, which is sometimes awkward, given a house with children who need to meet schedules, serious insomnia, and the fact that this is European Central Time. In practice, I just don't sleep much but, now aged a bit, an extra hour now and then would certainly be nice. (The composer La Monte Young and his partner, artist Marian Zazeela have lived for many years on schedules with days of more than 24 hours, phasing in and out with the standard clock. I greatly admire this robust independence; it's one thing to go to the beat of another drummer, but quite another to go to the tick of another clock).

*****

I don't wear a watch or carry any other portable device with the time-of-day built-in, and my attempt to do so have usually ended in loss or malfuction. Nevertheless, I still manage to be punctual, thanks to a pretty good internal sense of clock time and some help from the ample number of clocks hung about the house and in public (church towers and train stations are always handy sources of clocks).

But my internal clock does not extend to a capacity to estimate the length of a piece of music in terms of minutes and seconds. When a piece of music starts and I'm engaged by it, I go off the clock. In electronic music classes in college, the first question after playing a new study was almost always "how long was that?". I was always wrong about the duration in clock time but nevertheless, I don't think it inhibited my sense of whether a piece was over-indulgent with time.

While I suppose that that had some relevance in the days of lps and cds and before streaming radio eliminated some need to fit into strict broadcasting schedules, one of the opportunities of the moment in composition would seem to be no longer allowing these external factors to determine piece length, but rather letting material, method, and time structure at hand work out the optimal duration, whatever that might be.

Musicians -- who concertize in the evening -- are generally at a time-shift to the rest of the working population. I've got both that shift and a stubborn disinclination to ever shift out of Pacific Coast time, which is sometimes awkward, given a house with children who need to meet schedules, serious insomnia, and the fact that this is European Central Time. In practice, I just don't sleep much but, now aged a bit, an extra hour now and then would certainly be nice. (The composer La Monte Young and his partner, artist Marian Zazeela have lived for many years on schedules with days of more than 24 hours, phasing in and out with the standard clock. I greatly admire this robust independence; it's one thing to go to the beat of another drummer, but quite another to go to the tick of another clock).

*****

I don't wear a watch or carry any other portable device with the time-of-day built-in, and my attempt to do so have usually ended in loss or malfuction. Nevertheless, I still manage to be punctual, thanks to a pretty good internal sense of clock time and some help from the ample number of clocks hung about the house and in public (church towers and train stations are always handy sources of clocks).

But my internal clock does not extend to a capacity to estimate the length of a piece of music in terms of minutes and seconds. When a piece of music starts and I'm engaged by it, I go off the clock. In electronic music classes in college, the first question after playing a new study was almost always "how long was that?". I was always wrong about the duration in clock time but nevertheless, I don't think it inhibited my sense of whether a piece was over-indulgent with time.

While I suppose that that had some relevance in the days of lps and cds and before streaming radio eliminated some need to fit into strict broadcasting schedules, one of the opportunities of the moment in composition would seem to be no longer allowing these external factors to determine piece length, but rather letting material, method, and time structure at hand work out the optimal duration, whatever that might be.

Sunday, March 11, 2007

Tempered

I received a few emails about my post on Morton Feldman's Piano and String Quartet, and one of them concerned my use of the terms "tempered" and "untempered". While in everyday usage, "untempered" would suggest some unruliness or lack of control, in this musical context, nothing of the sort is intended.