Darcy James Argue (here and here) writes about Fanservice, a term new to me, and apparently associated first with Japanese superhero comics (about which I know nothing), in which extraneous and gratuitous content, much of it sexual in nature and frequently referential only to other Fanservice, but non-essential to the plot of the work in hand is added solely in order to provide a bonus for the long-time insider, a reward for investing ever-more time and attention to a comic series. Argue goes beyond this to generalize the term to other art forms, and stresses the insider/outside social dimension of a practice that simultaneously panders to those in the know and alienates newcomers and those who are not yet fully initiated into the local cant and code.

While there are many cases in which a broad consensus would agree that a feature is non-essential, gratuitous, and obscure to a novice consumer (and thus pure Fanservice), an extension of the term to similar features in other genres creates some real problems. Details in a work of music, or literature, or dance or film create texture, depth, and may as often be cues as miscues as to the course of the work (like stage magic, these art forms are all about misdirection).* The presence of a wealth of details help to create the illusion that the universe in the work of art is as complex, confusing, contradictory and coherent as the natural world about it (someone once asked the great question of a work of literature: is it wierd enough to be realistic?). The detective story is probably the form in which this characteristic is most essential, as the presence of detail in the story which is, ultimately, irrelevant to the solution of the mystery is required to both sustain the readers' attention to the detective work and to add to the plausibility of the scenario through enriching the texture.

In the end, whether content is fanservice or just generous detail is, I suppose, entirely in the mind of the body being serviced. There is an argument, associated with modernism, that anything extraneous and non-essential to a work should be eliminated but there is also a modernist argument that a work should be encyclopedic, emulating a universe in the diversity (and often even the obscurity) of its contents. There is no resolution to these two arguments and, just as with unresolved contradictions in music, I happen to find this a perfectly cheerful state of affairs.

(I just noticed that Tim Rutherford-Johnson opens the discussion even further, and more wisely than I, here.)

_____

* My friend Tom Hilton loved to point out a passage in B. Traven's The Death Ship, which bops along in an entirely plausible mode until someone mentions the town of "Chi(cago), Wisconsin", an error, perhaps, but one which nags at the reader, who at this point may wonder if the entire book has suddenly decohered from familar spacetime.

A displaced Californian composer writes about music made for the long while & the world around that music. ~ The avant-garde is flexibility of mind. — John Cage ~ ...composition is only a very small thing, taken as a part of music as a whole, and it really shouldn't be separated from music making in general. — Douglas Leedy ~ My God, what has sound got to do with music! — Charles Ives

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Open it up!

Bart Collins of the Well-Tempered Blog reports that a number of manuscripts have been discovered in Poland which might be "new" works of Mozart. The online stories indicate that the specialists have been gathered to render judgement on the provenance and authority of the works. That's standard musicological operating procedure ("SMOP").

However, online technology, and that of blogging in particular, offers a serious alternative to SMOP: Good images of the manuscripts can be placed online as soon as possible, allowing analysis and discussion to be carried out by as broad a community as possible rather than a select group of professionals. On numerous occasions, online communities have already demonstrated considerable competence in investigations of this sort, both confirming, complementing, and challenging the work done by professional scholars.

Such a process would necessarily require that parties most immediately associated with the discoveries have to give up a bit of their conventional SMOP rights to control first performances, publication, and even some of the authority associated with a first report in print on the authenticity of the documents. However, as scholars, isn't the greater interest in the work itself, not the collection of scholarly feathers-in-mortar-boards or in the prestige of publication by a traditional publishing house. I believe that this is the case for musical works by composers whose catalogs are otherwise long part of the public domain, and acutely so for works of substantial musical quality, for which getting the work out (published, played, heard) is more important that being the first to do so.

It may be argued that an open vetting of a question like the provenance of a musical manuscript would be a messy and inconclusive process. The famous example of the alleged military service documents of George W. Bush is frequently taken as a case in point. However, I believe that those documents are, in fact, a very good illustration of the advantages of an open process. I believe that it's fair to conclude that the open online discussion reached a consensus on two points, and a consensus that may well be familiar to scholars of music: the first point was that the documents were modern forgeries, but the second point was that the content of the documents appears not to have contradicted in any substantial way the known circumstances and events of Mr. Bush's military performance. (In other words, the documents were fake but their content was true, a combination entirely plausible in the world of music.) In both the documents and the historical context, the online community was able to bring considerable resources and expertise, far exceeding those of the news organization which first publicized the documents. Had CBS News first placed the documents online for such thorough perusal and discussion before making their prime time report, Dan Rather might still be reading the evening news, an example that contemporary music scholars may wish to examine in considering the possible advantages of an open inquiry over SMOP.

However, online technology, and that of blogging in particular, offers a serious alternative to SMOP: Good images of the manuscripts can be placed online as soon as possible, allowing analysis and discussion to be carried out by as broad a community as possible rather than a select group of professionals. On numerous occasions, online communities have already demonstrated considerable competence in investigations of this sort, both confirming, complementing, and challenging the work done by professional scholars.

Such a process would necessarily require that parties most immediately associated with the discoveries have to give up a bit of their conventional SMOP rights to control first performances, publication, and even some of the authority associated with a first report in print on the authenticity of the documents. However, as scholars, isn't the greater interest in the work itself, not the collection of scholarly feathers-in-mortar-boards or in the prestige of publication by a traditional publishing house. I believe that this is the case for musical works by composers whose catalogs are otherwise long part of the public domain, and acutely so for works of substantial musical quality, for which getting the work out (published, played, heard) is more important that being the first to do so.

It may be argued that an open vetting of a question like the provenance of a musical manuscript would be a messy and inconclusive process. The famous example of the alleged military service documents of George W. Bush is frequently taken as a case in point. However, I believe that those documents are, in fact, a very good illustration of the advantages of an open process. I believe that it's fair to conclude that the open online discussion reached a consensus on two points, and a consensus that may well be familiar to scholars of music: the first point was that the documents were modern forgeries, but the second point was that the content of the documents appears not to have contradicted in any substantial way the known circumstances and events of Mr. Bush's military performance. (In other words, the documents were fake but their content was true, a combination entirely plausible in the world of music.) In both the documents and the historical context, the online community was able to bring considerable resources and expertise, far exceeding those of the news organization which first publicized the documents. Had CBS News first placed the documents online for such thorough perusal and discussion before making their prime time report, Dan Rather might still be reading the evening news, an example that contemporary music scholars may wish to examine in considering the possible advantages of an open inquiry over SMOP.

Monday, May 26, 2008

More not being there.

Sometimes when you simply let a score go off on its own into the world, very good things happen.

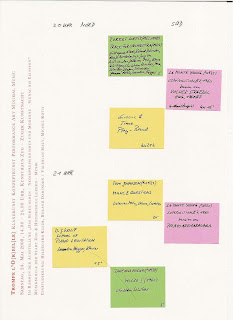

My School of Levitation, a set of etudes for piano with a score made up entirely of brief prose instructions (it's here, if you like), was played last Saturday in Zug, Switzerland on a program of conceptual and minimalist works including pieces by Young, Brown, Lucier, Kosugi, Ichiyinagi, Reich, Glass & Johnson (all personal heroes). I had written the etudes for Hildegard Kleeb, my favorite pianist, or more accurately, as projects for Hildegard to realize with her students. In the concert in Zug, they were played by Leandra Högger, a young pianist studying in Lucerne.

The first etude uses a very simple process, in which the arms begin crossed and slowly move to the opposite end of the keyboard, by a combination of accumulated errors in repetition and the natural relaxation of the arms. Hildegard writes that

She took a lot of time and space to play quietly and the first Etude lasted about 20 minutes.

I had never imagined a performance of that length, but now it seems exactly right.

In the third Etude, Catching Butterflies, the pianist is asked to speak a series of words into the open piano, pedal down, and then to reproduce prominent resonances of each word on the keyboard. I had left the choice of words up to the pianist, but was totally delighted to learn that, in Zug

In the 3rd etude she used names of butterflies.

The idea had never occurred to me. Now, it's hard to imagine any other text. Has anyone else ever noticed that, in no matter which language, the names of butterflies sound extraordinary?

Not. Easy.

Dennis Báthory-Kitsz responds to a post of mine from earlier this year. With all due respect and affection, I disagree with almost everything Dennis writes. Let's go through this item by item:

Music is easy.

There is no monolithic music, music is plural: while some music is blissfully easy, other music is entirely uneasy, and much music wanders with all determination in the space in-between.

Its actual content is insubstantial.

Music, the temporal art par excellence, is transitory, but it is not insubstantial. It's pushing wave fronts around in real space and in real time, and the physical impact of that motion is thrillingly real.

It is about clever noises,

Noises are not clever, but they may be used as cleverly or idiotically as one may, and our interest in those noises is precisely in their application.

and all the numerical pomp brought into it by modernists or discovered in the baroque by musicologists is as meaningless as the educational spout that claims music offers the benefits of greater intellectual acuity or physical coordination.

I don't follow this at all -- are you suggesting that music cannot have a depth and complexity to reward intellectual or physical engagement?

It makes no valuable contributions to human progress,

While I can't, personally, find much utility in the phrase "human progress", I can immediately recognize that music is one record of the current state of the human condition, and a state often -- and tellingly -- independent from political economy or technological resources.

(But if we do wish to reduce music to a "contribution to human progress", certain technical developments are directly due to music, for example the regulation of air pressure in the wind chest in the hydraulis or the opposable crank on the hurdy-gurdy. More impressively, it is entirely plausible that the material needs which were answered by the invention of the mechanical clock, in which a fixed and repeating unit of time was divided precisely at several levels, emerged only in the continent, Europe, in which musical counterpoint and its notation had been developed.)

it is pitifully self-referential,

Why should self-referentiality be pitied? Isn't there precious value in imagined worlds -- of music or other art forms, design, mathematics, theology -- in which the point of departure is the familiar, but through disciplined, internally consistent work, new worlds are constructed that are orthogonal to and enriching of everyday experience.

it is a garbled and inconsistent means of communication, it has nothing to communicate but the personal and unarguable choices of the artists, and it is hardly worth that angst brought to it by so many nascent composers.

Again, music is plural, and plural from its very origins. While music shares physiological organs and cognitive apparatus with speech and one form of music originates in and continues to be a heightened form of speech, and although music may well be held to be "garbled" when tasked with communicative acts that speech alone does with superb clarity and efficiency, music does in fact have capacities to communicate aspects of experience, and our experience of space and time in particular, that plain speech does terribly, if at all. What an astonishing continuum music occupies! On one end, nothing says I love you better than breaking out into song, while on the other end, nothing allows one to pass time better than making noises that joyfully articulate the experience of time passed.

Debate that and risk getting outed.

Risk welcomed.

There. I've said it. Music doesn't create world peace or make a better sandwich.

Here. I'll say it: One does not ask music to interact with the rest of the world in a simple causal relationship. But music can be sign and symptom of a world at peace or even well-fed. The state of music in a culture can be sign and symptom of how peace is valued in that culture, and taste in music is often usefully parallel to taste in food (among other things): certainly in the West, the coexistence of fast and slow food cultures is precisely mirrored by the diversity in quality, substance, and function of the various musical cultures. (See my post on Slow Listening, here).

But if music and the world around it are not in a simple causal relationship, I believe that valuing music and, in turn, the values one finds in music may well be a necessary precondition for a world in which peace, or yes, even just a better sandwich, is valued.

Music is easy.

There is no monolithic music, music is plural: while some music is blissfully easy, other music is entirely uneasy, and much music wanders with all determination in the space in-between.

Its actual content is insubstantial.

Music, the temporal art par excellence, is transitory, but it is not insubstantial. It's pushing wave fronts around in real space and in real time, and the physical impact of that motion is thrillingly real.

It is about clever noises,

Noises are not clever, but they may be used as cleverly or idiotically as one may, and our interest in those noises is precisely in their application.

and all the numerical pomp brought into it by modernists or discovered in the baroque by musicologists is as meaningless as the educational spout that claims music offers the benefits of greater intellectual acuity or physical coordination.

I don't follow this at all -- are you suggesting that music cannot have a depth and complexity to reward intellectual or physical engagement?

It makes no valuable contributions to human progress,

While I can't, personally, find much utility in the phrase "human progress", I can immediately recognize that music is one record of the current state of the human condition, and a state often -- and tellingly -- independent from political economy or technological resources.

(But if we do wish to reduce music to a "contribution to human progress", certain technical developments are directly due to music, for example the regulation of air pressure in the wind chest in the hydraulis or the opposable crank on the hurdy-gurdy. More impressively, it is entirely plausible that the material needs which were answered by the invention of the mechanical clock, in which a fixed and repeating unit of time was divided precisely at several levels, emerged only in the continent, Europe, in which musical counterpoint and its notation had been developed.)

it is pitifully self-referential,

Why should self-referentiality be pitied? Isn't there precious value in imagined worlds -- of music or other art forms, design, mathematics, theology -- in which the point of departure is the familiar, but through disciplined, internally consistent work, new worlds are constructed that are orthogonal to and enriching of everyday experience.

it is a garbled and inconsistent means of communication, it has nothing to communicate but the personal and unarguable choices of the artists, and it is hardly worth that angst brought to it by so many nascent composers.

Again, music is plural, and plural from its very origins. While music shares physiological organs and cognitive apparatus with speech and one form of music originates in and continues to be a heightened form of speech, and although music may well be held to be "garbled" when tasked with communicative acts that speech alone does with superb clarity and efficiency, music does in fact have capacities to communicate aspects of experience, and our experience of space and time in particular, that plain speech does terribly, if at all. What an astonishing continuum music occupies! On one end, nothing says I love you better than breaking out into song, while on the other end, nothing allows one to pass time better than making noises that joyfully articulate the experience of time passed.

Debate that and risk getting outed.

Risk welcomed.

There. I've said it. Music doesn't create world peace or make a better sandwich.

Here. I'll say it: One does not ask music to interact with the rest of the world in a simple causal relationship. But music can be sign and symptom of a world at peace or even well-fed. The state of music in a culture can be sign and symptom of how peace is valued in that culture, and taste in music is often usefully parallel to taste in food (among other things): certainly in the West, the coexistence of fast and slow food cultures is precisely mirrored by the diversity in quality, substance, and function of the various musical cultures. (See my post on Slow Listening, here).

But if music and the world around it are not in a simple causal relationship, I believe that valuing music and, in turn, the values one finds in music may well be a necessary precondition for a world in which peace, or yes, even just a better sandwich, is valued.

Friday, May 23, 2008

Not being there

An email came late last night announcing that a piece of mine would be played tomorrow in Switzerland. The news was a complete -- and pleasant -- surprise. In principle, everything could be dropped, a babysitter arranged, tickets purchased, bags packed, and in a matter of hours I could be in the Alps listening to my piece (it'll be a concert premiere of work intended for studio performance). But there is also a principle to just letting it go on: a score like mine can go out into the world without my further assistance, like a love letter addressed to whom it may concern. After all, I already know how it goes...

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Landmarks (33)

Arnold Schoenberg: String Trio (for Violin, Viola and Cello) op. 45 (1946)

Like all of Schoenberg's strongest works, the String Trio was written in an brief and intense period of time; several of these pieces were composed at times associated with dramatic personal events, in this case a medical crisis (see here).

Schoenberg named his book of collected essays Style and Idea; the contrast between the intuitive and expressive, even precognitive, qualities implied by the term style and the formal, mental, conscious qualities carried by the term idea is ever-present in Schoenberg's music. These qualities are inevitably in tension, but in his best works that tension becomes both a propulsive and cohesive force.

I find that Schoenberg's least convincing pieces are those in which technique is speaking louder than style; this is frankly true of some of the twelve-tone works, with the Wind Quintet an especially labored example. But in the late Trio (as well as the violin and piano Phantasy and A Survivor from Warsaw), the composer found a balance between his native musical language, a heightened Wiener Espressivo, and the rigor of the twelve-tone method.

That is not to say that the work is an easy one: Schoenberg's expressionist style is, for many listeners and musicians, more off-putting than his technique (which, in principal, is abstract and can be composed-out in a variety of styles, some of them altogether different from expressionism). And although a kind of free tonal expressionism has become widely familar (at least as a fixed trope in film music) it remains a style that is as uneasy now as it ever was, and was never intended to be anything other than uneasy.

Although Schoenberg would later explain (to Thomas Mann, as reported in The Story of a Novel) that the Trio was a reflection of his psychological and physical state at the time, the work is carried by a formal structure that is ultimately independent of any simple biographical narrative. It is program music, but the more substantial narrative is musical not literal. The three parts separated by episodes of the single movement work may or may not correspond directly to autobiographical episodes, but this is inessential; what is important is that the musical continuity, the musical narrative, is gripping and convincing on its own terms.

As heightened as the expression may be, the Trio is never heavy-handed with its emotions; its tone is often clinical, and the pain and fear are observed, not pushed on the listener. Central to the tone is Schoenberg's command of string writing (he was a string player himself) and the timbral possibilities of the instruments are used brilliantly everywhere to both project the intensity of the musical narrative and to spring out of any constraints the rigorous tonal structure might suggest. The tone of the strings here is subtle, sensitive, exposed and -- especially when agitated and loud -- vulnerable, suggesting that the composer needed to use the instruments he knew most intimately to handle that vulnerability, that fragility.

Like all of Schoenberg's strongest works, the String Trio was written in an brief and intense period of time; several of these pieces were composed at times associated with dramatic personal events, in this case a medical crisis (see here).

Schoenberg named his book of collected essays Style and Idea; the contrast between the intuitive and expressive, even precognitive, qualities implied by the term style and the formal, mental, conscious qualities carried by the term idea is ever-present in Schoenberg's music. These qualities are inevitably in tension, but in his best works that tension becomes both a propulsive and cohesive force.

I find that Schoenberg's least convincing pieces are those in which technique is speaking louder than style; this is frankly true of some of the twelve-tone works, with the Wind Quintet an especially labored example. But in the late Trio (as well as the violin and piano Phantasy and A Survivor from Warsaw), the composer found a balance between his native musical language, a heightened Wiener Espressivo, and the rigor of the twelve-tone method.

That is not to say that the work is an easy one: Schoenberg's expressionist style is, for many listeners and musicians, more off-putting than his technique (which, in principal, is abstract and can be composed-out in a variety of styles, some of them altogether different from expressionism). And although a kind of free tonal expressionism has become widely familar (at least as a fixed trope in film music) it remains a style that is as uneasy now as it ever was, and was never intended to be anything other than uneasy.

Although Schoenberg would later explain (to Thomas Mann, as reported in The Story of a Novel) that the Trio was a reflection of his psychological and physical state at the time, the work is carried by a formal structure that is ultimately independent of any simple biographical narrative. It is program music, but the more substantial narrative is musical not literal. The three parts separated by episodes of the single movement work may or may not correspond directly to autobiographical episodes, but this is inessential; what is important is that the musical continuity, the musical narrative, is gripping and convincing on its own terms.

As heightened as the expression may be, the Trio is never heavy-handed with its emotions; its tone is often clinical, and the pain and fear are observed, not pushed on the listener. Central to the tone is Schoenberg's command of string writing (he was a string player himself) and the timbral possibilities of the instruments are used brilliantly everywhere to both project the intensity of the musical narrative and to spring out of any constraints the rigorous tonal structure might suggest. The tone of the strings here is subtle, sensitive, exposed and -- especially when agitated and loud -- vulnerable, suggesting that the composer needed to use the instruments he knew most intimately to handle that vulnerability, that fragility.

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Burning

Firefighters are working at this moment to put out a major fire in the Berliner Philharmonie. The fire occured during the time of an afternoon concert, which was halted and all audience and musicians were able to leave the building. The home of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the hall was built in 1960-63, designed by architect Hans Scharoun. It has been reported that the cause of the fire was welding near the insulation beneath the roof and initial reports indicate that, barring water damage from the fire control, the concerts in the hall scheduled for this weekend should be able to take place.

Update: The fire has been controlled without injuries or damage to the instrument collection, but all concerts in the main hall have tentatively been canceled.

Update: The fire has been controlled without injuries or damage to the instrument collection, but all concerts in the main hall have tentatively been canceled.

Whadayaknow?

What of music, and the world about music, does a composer have to know? While one generally supposes that knowing more rather than knowing less is a better default setting, there are plenty of fine musicians who get along, with music & the world, just swell on a need-to-know basis.* More than a few composers have come to art music via popular musics or film or visual art or performance art or maths or what have you, and are active and perfectly successful without a traditional command of theory or even notation. Some musicians even exercise a form of self-induced deafness, to tactically shut out potential areas of influence in order or even to insure that one's inventions are more honestly one's own.

I use the word useful a lot on these pages; in a musical scene with a lively diversity of activity, it's damn next to impossible to claim that, as in the old conservative conservatory days, there was a curriculum to which a consensus canon and code could be agreed. Instead, the only criterion is usefulness: does some bit of knowledge lead productively to interesting new work?

*****

There's an important interview (Ithinks) in the current issue of MusikTexte with James Ingram, who was Stockhausen's copyist from 1974 to 2000. Ingram was, by all accounts, not just a copyist but was absolutely critical for Stockhausen in establishing his publishing house after the composer's breakup with Universal Edition and he produced meticulous scores with a distinctive house style. This included making a transition to computer-based engraving which, in Stockhausen's case, required the development of unique fonts as well as tools for directly manipulating the score image, moreover, working within the composer's household workshop, Ingram was able to revise and edit any score in progress with a flexibility and immediacy not possible in traditional publishing structures.

Naturally, anyone with such close contact to a figure like Stockhausen will have observed a lot of interesting things (i.e. Stockhausen's preference for the manually controlled oscillators in the original version of Studie II over a later, computer-generated version, a preference which is reiterated in the realization of his late electronic work Cosmic Pulses from the unfinished Klang cycle), but one observation, or rather non-observation stuck-out for me, and that was Ingram's response to the question of How much music did Stockhausen know? And Ingram's answer, that he seldom listened to music other than his own strikes me as entirely plausible, and entirely telling. Ingram speculates that he didn't want to know other music -- it's a way of circumventing questions of influence or even claims of plagiarism** and his own biography coincides precisely with that stretch of German history in which a premise of beginning from nothing was widely shared and a precondition to this was a very careful forgetting of the past. (I believe that this premise was even more consequently applied by Stockhausen that by any of his contemporaries in the literary zero hour (Stunde Null)).

To my ears, a paradoxical effect of Stockhausen's distance to other music, and particularly to other contemporary music, is that because his own music did not enter into dialog with its contemporaries, it often does not feel modern and of the moment, but exhibits rather a kind of nostalgia for the modernity of an era past. Much as Varese's futurism or ultramodernism remained that of the 1920's, Stockhausen's was very much stuck in that of the 1950's and early 1960's. I was struck by this first with the -- altogether charming -- little set of melodies, Tierkreis (1974-75) which, especially in their harmonized versions, apply a voice leading that is comfortably located in a harmonic cul de sac right off the insection between Messiaen and Hindemith. Stockhausen's subsequent tonal practice, from Sirius through Licht, confirmed this impression with his use of the prolongation and diminution of basic melodic formulae reinforcing this quality.

_____

* As long as I'm at it, I think that -- all else being equal -- it's probably better that a composer have being nice rather than being a jerk as a default temperament setting, but neither quality is an automatic precondition to musical and social success. Unfortunately, Clio provides plenty of evidence that plenty of jerks rise to Parnassus and plenty of nice folk finish last. But then again, I never got an "A" in "gets along with others", so you may discount my opinion appropriately.

**It is, for example, impossible to escape the specific influence that La Monte Young's work had on Stockhausen's Stimmung and, likewise, the use of a nine-limit tonality diamond in his Sternklang must have come from Harry Partch, but in other cases, like that of a possible connection between Feldman's Intermission 6 (1953) and Stockhausen's Klavierstück XI (1956) can be more probably assigned to the realm of good ideas that are simply of a moment in which independent discovery is possible.

I use the word useful a lot on these pages; in a musical scene with a lively diversity of activity, it's damn next to impossible to claim that, as in the old conservative conservatory days, there was a curriculum to which a consensus canon and code could be agreed. Instead, the only criterion is usefulness: does some bit of knowledge lead productively to interesting new work?

*****

There's an important interview (Ithinks) in the current issue of MusikTexte with James Ingram, who was Stockhausen's copyist from 1974 to 2000. Ingram was, by all accounts, not just a copyist but was absolutely critical for Stockhausen in establishing his publishing house after the composer's breakup with Universal Edition and he produced meticulous scores with a distinctive house style. This included making a transition to computer-based engraving which, in Stockhausen's case, required the development of unique fonts as well as tools for directly manipulating the score image, moreover, working within the composer's household workshop, Ingram was able to revise and edit any score in progress with a flexibility and immediacy not possible in traditional publishing structures.

Naturally, anyone with such close contact to a figure like Stockhausen will have observed a lot of interesting things (i.e. Stockhausen's preference for the manually controlled oscillators in the original version of Studie II over a later, computer-generated version, a preference which is reiterated in the realization of his late electronic work Cosmic Pulses from the unfinished Klang cycle), but one observation, or rather non-observation stuck-out for me, and that was Ingram's response to the question of How much music did Stockhausen know? And Ingram's answer, that he seldom listened to music other than his own strikes me as entirely plausible, and entirely telling. Ingram speculates that he didn't want to know other music -- it's a way of circumventing questions of influence or even claims of plagiarism** and his own biography coincides precisely with that stretch of German history in which a premise of beginning from nothing was widely shared and a precondition to this was a very careful forgetting of the past. (I believe that this premise was even more consequently applied by Stockhausen that by any of his contemporaries in the literary zero hour (Stunde Null)).

To my ears, a paradoxical effect of Stockhausen's distance to other music, and particularly to other contemporary music, is that because his own music did not enter into dialog with its contemporaries, it often does not feel modern and of the moment, but exhibits rather a kind of nostalgia for the modernity of an era past. Much as Varese's futurism or ultramodernism remained that of the 1920's, Stockhausen's was very much stuck in that of the 1950's and early 1960's. I was struck by this first with the -- altogether charming -- little set of melodies, Tierkreis (1974-75) which, especially in their harmonized versions, apply a voice leading that is comfortably located in a harmonic cul de sac right off the insection between Messiaen and Hindemith. Stockhausen's subsequent tonal practice, from Sirius through Licht, confirmed this impression with his use of the prolongation and diminution of basic melodic formulae reinforcing this quality.

_____

* As long as I'm at it, I think that -- all else being equal -- it's probably better that a composer have being nice rather than being a jerk as a default temperament setting, but neither quality is an automatic precondition to musical and social success. Unfortunately, Clio provides plenty of evidence that plenty of jerks rise to Parnassus and plenty of nice folk finish last. But then again, I never got an "A" in "gets along with others", so you may discount my opinion appropriately.

**It is, for example, impossible to escape the specific influence that La Monte Young's work had on Stockhausen's Stimmung and, likewise, the use of a nine-limit tonality diamond in his Sternklang must have come from Harry Partch, but in other cases, like that of a possible connection between Feldman's Intermission 6 (1953) and Stockhausen's Klavierstück XI (1956) can be more probably assigned to the realm of good ideas that are simply of a moment in which independent discovery is possible.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Presence

Last Wednesday, I was treated to an evening of music for solo string instruments, two rarities: a baroque baryton (or viola paradon) and an 'ûd kâmil-i buzurg, the scholar's lute of the later Timurid empire, played, respectively, by Roswitha Bruggaier and Danyel Franke. In advance, Franke warned us of the low amplitude of the music, noting that the small hall (perhaps 40 people in the room) was already too large, and that, in fact, the instruments were both intended to be played for an audience of one, the player him- or herself, suggesting a certain violation of intimacy in bringing the music, an improvised Taqsim, a baroque partita by Krause, (both in an historically-informed performance style) and two new solo works by Franke, to a public even as small as ours.

I think, though, that Danyel Franke's warning and intimated violation of privacy were unneccessary. While both instruments were, in terms of modern concert instruments, extremely soft, each was perfectly audible, even in a room, with glass walls facing an unquiet street, and bodied enough by live, breathing and shifting human beings, that should have hardly been appropriate to musical intimacy. But it worked just fine. After initial adjustments in bodies, ears, and attentions, every nuance of sound was simply present. It was not even a question of competing with the street or random body noises, as the sounds unfolding in musical time made by the musicians on those particular instruments were so special, so unlike anything else about us in the casual rhythms of everyday, that talk of competition would be an irrelevancy.

*****

I happen to be a great advocate of electronic sound amplification, but only when it is used as an appropriate technology. Such is our general disregard for the qualities of particular sounds that we too often assume that a sound has got to be assisted by amplified and loudspeakers in order to be heard. In the worst cases, amplification is chosen specifically so that listeners will be forced to hear something and to hear it in one specific way (in other words, a choice is made that others will have no choice). As bad as this practice may be in developed countries, it has been my experience that amplification is especially abused in the developing world, where its use is at once an emblem of modernity and wealth, but also clearly a tool for public control. The costs to the musical experience are, in my opinion, often far too high, as nuance and detail gets lost to the mix, artifacts of electro-acoustic transmission, and the social competition for a position in front of a microphone.

At one of my universities, we had fairly regular concert visits by Q'in players. The q'in, the Chinese "scholar's lute" is an instrument of even less absolute volume than either of the instruments played Wednesday evening. Inevitably, each guest musician would insist upon amplification, on the premise that their instrument could not otherwise be heard, and the faculty member responsible for the PA system would politely go through the routines of setting up mic, amp, and speakers and holding brief a sound check with the player. But during the concert -- and I observed this at least four times -- said Professor would simply turn the sound system off. And no one -- the player included -- ever complained. They was, in fact, nothing to complain about, as every sound was perfectly perceptible, even when scarcely audible, as the q'in had an acoustical presence that was both so attractive and so distinctive that it was inescapable and even, in some moments, reached a near-deafening intensity.

At one of my universities, we had fairly regular concert visits by Q'in players. The q'in, the Chinese "scholar's lute" is an instrument of even less absolute volume than either of the instruments played Wednesday evening. Inevitably, each guest musician would insist upon amplification, on the premise that their instrument could not otherwise be heard, and the faculty member responsible for the PA system would politely go through the routines of setting up mic, amp, and speakers and holding brief a sound check with the player. But during the concert -- and I observed this at least four times -- said Professor would simply turn the sound system off. And no one -- the player included -- ever complained. They was, in fact, nothing to complain about, as every sound was perfectly perceptible, even when scarcely audible, as the q'in had an acoustical presence that was both so attractive and so distinctive that it was inescapable and even, in some moments, reached a near-deafening intensity.*****

I think sometimes that in composing, and especially in orchestration, it might be useful to get away from a focus on balancing elements and focus instead on the assertion of the individual presences of musical sounds, whether from voices or instruments. In principle, it should be possible to have, let's say, a trombone (the standard orchestral instrument with the highest possible decibel output) playing at the same time as a lute and be able to perceive both, provided the composition projects the individual characteristics of each instrument. (The late Henry Brant -- following the model of Charles Ives -- smartly used spatial separation of instrumental and vocal forces to achieve a polyphony of forces often unperturbed by unequal amplitudes).

*****

These ideas about presence are scarcely my own; they are in debt to Gordon Mumma, Alvin Lucier, Hauke Harder, and the artist Robert Irwin.

Thursday, May 15, 2008

A tragedy of the common

This is the course of the world: that where we think ourselves surest, there are we furthest off from our purpose. -- Thomas MorleyI've been having the pleasure of re-reading Morley's Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (1597), pleasure, combined with that shock, once again, of recognizing, behind the immediate difficulties of the language, a clear, systematic, and -- in my opinion -- modern accounting of an art of music and a book of ideas for potential music making (his accounting of rhythm, for example, is so rich is possibilities that Anglophones had to wait until Henry Cowell's New Musical Resources of 1930 for a substantial companion volume).

But at the same time, reading Morley is a melancholy experience, for he was writing at a moment in which a musician-scholar could meaningfully survey an entire repertoire, shared by a community of musicians and listeners. And in that community, there was a shared repertoire of whole pieces, forms, figures, & rules to be replicated, extended, & -- judiciously -- broken. The melancholy comes with the recognition that such a moment is long behind us. Now, each composer sets her or his own rules, independent of a community, and if a rule is broken, it's like the the proverbial tree falling in the forest: who's to know?

A friend, David Feldman, call this my "tragic dimension": if I understand him correctly, on the one hand, this is being aware that all is possible but that that richness of possibility comes at the cost of a loss of commonality, while on the other hand, it is the awareness that through new compositional techniques, experiments, one may come close to successfully replicating elements of familiar musics, but one may well also fail, and it's not at all clear how success and failure are distinguished, let alone predicted. I can't deny the tragic side of this, but my working premise has been that there is potential for richness to be found precisely in the tension between the common and the wider field of unexplored possibilities around the common. Moreover, adopting an experimental discipline requires that one learn to take cheer from failure as well as from success.

Treasuring the common; looking for common ground. A habit, a folly even, is collecting ground basses -- chromatic lamentos, Passamezzi antico or modern, La Folia (of course), and passacaglias and chaconnes of any length or flavor -- and they can, indeed, ground your work, allowing experiments with figures above and below, but also making a connection to the commons. Some people collect stamps or potato mashers, I collect ground basses. Having cake and eating it, too. Having archaic...

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Complexity and Stuff

While there are countless conceptions or definitions of complexity, there are two sorts of complexity that are probably most relevant to music. One is basically quantitative: the impression of complexity due to the amount of stuff squeezed into a piece. The other is qualitative and due to wonder about how the stuff, whatever quantity there may be of it, is connected, within and without the world of a piece. While a composer can certainly push an extreme of quantity up or down into a state of inescapable wonder, my own taste certainly runs more in the direction of pushing quality to extremes, where wonder is an option, not forced.

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Are we good?

Blogging economist Brad De Long observes that:

A good college--visible or invisible--is composed of people who (a) know stuff, and (b) think well. The best colleges are made up of people who know different stuff, who think well in different ways, and who--most important--understand that when they listen to people who know different stuff than they do and who think well in different ways than they do, they learn.

Substitute "music school" or "new music blog" for "college": maybe the new music blogs, taken in aggregate, aren't so bad after all.

A good college--visible or invisible--is composed of people who (a) know stuff, and (b) think well. The best colleges are made up of people who know different stuff, who think well in different ways, and who--most important--understand that when they listen to people who know different stuff than they do and who think well in different ways than they do, they learn.

Substitute "music school" or "new music blog" for "college": maybe the new music blogs, taken in aggregate, aren't so bad after all.

Monday, May 12, 2008

Old/new quote/unquote

Donald Rumsfeld:

"Now, you're thinking of Europe as Germany and France. I don't. I think that's old Europe. If you look at the entire NATO Europe today, the center of gravity is shifting to the east. And there are a lot of new members. And if you just take the list of all the members of NATO and all of those who have been invited in recently -- what is it? Twenty-six, something like that? -- you're right. Germany has been a problem, and France has been a problem."

Kyle Gann:

"...and we agreed today that, if the old music world was France, Germany, and Elliott Carter, the new one is more typically The Netherlands, Serbia, and Downtown."

*****

The Obama era can't come fast enough. The world is a subtle, diverse, and complex place, and quality can be found anywhere, as well as disaster. We need to be more grown-up about this rather than continue to trade in petulant blanket categorizations and prejudices. The "old worlds" were never as monolithic as all that, and a failure to recognize that is just echoing the sins of those who most benefit from the monolithic image. (Need anyone be reminded that it was that "old European", German Green Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer who stood up to Rumsfeld in advance of the Iraq adventure and stated as clearly as possible that he "was not convinced"?) Yes, let's call out the old institutions and the Boulezes or Carters of the world when they play ugly musical politics, but let's also take music as music, rather than the music-political currency of a given faction or cohort, even if we risk giving the music of others more respect that was ever or will be shown in return. Yes, there are (and will always be) musical factions and cohorts, gathered by various forms of affinity, convenience, or caprice, but in the real new music world, these are no longer distinct communities primarily built around geographical borders and ethnological affinity defending a common repertoire but are instead networks of aesthetic affinities sharing information and resources with overlapping but not exclusive repertoire.

"Now, you're thinking of Europe as Germany and France. I don't. I think that's old Europe. If you look at the entire NATO Europe today, the center of gravity is shifting to the east. And there are a lot of new members. And if you just take the list of all the members of NATO and all of those who have been invited in recently -- what is it? Twenty-six, something like that? -- you're right. Germany has been a problem, and France has been a problem."

Kyle Gann:

"...and we agreed today that, if the old music world was France, Germany, and Elliott Carter, the new one is more typically The Netherlands, Serbia, and Downtown."

*****

The Obama era can't come fast enough. The world is a subtle, diverse, and complex place, and quality can be found anywhere, as well as disaster. We need to be more grown-up about this rather than continue to trade in petulant blanket categorizations and prejudices. The "old worlds" were never as monolithic as all that, and a failure to recognize that is just echoing the sins of those who most benefit from the monolithic image. (Need anyone be reminded that it was that "old European", German Green Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer who stood up to Rumsfeld in advance of the Iraq adventure and stated as clearly as possible that he "was not convinced"?) Yes, let's call out the old institutions and the Boulezes or Carters of the world when they play ugly musical politics, but let's also take music as music, rather than the music-political currency of a given faction or cohort, even if we risk giving the music of others more respect that was ever or will be shown in return. Yes, there are (and will always be) musical factions and cohorts, gathered by various forms of affinity, convenience, or caprice, but in the real new music world, these are no longer distinct communities primarily built around geographical borders and ethnological affinity defending a common repertoire but are instead networks of aesthetic affinities sharing information and resources with overlapping but not exclusive repertoire.

Friday, May 09, 2008

Twice-tagged

This is for Paul Bailey and Steve Hicken, who know why:

The Captain, a stranger, now enters with Arlecchino. He says he has come from Spain to find his brother, married to a woman in Rome these many years. They knock at the door of the inn.

The Captain, a stranger, now enters with Arlecchino. He says he has come from Spain to find his brother, married to a woman in Rome these many years. They knock at the door of the inn.

Tuesday, May 06, 2008

In a Garden of Branching Websites

I spent an hour or so of procrastination time this morning trying to figure out how to travel to the Republic of Kalmykia. It's possible, in theory, but if you want to book ahead of time, you can't get there from here. Maybe that's okay, as Kalmykia, the nation that, by any modest powers of reason or imagination, ought to be the most interesting place in Europe, has been so worn down by the last century of external control and half-hearted Soviet-style modernisation, that any journey there is likely to be disappointing.

Websites, full of links internal, external, and infernal, were supposed to be the ideal medium from getting from some idea of here to some other idea of there and eventually to some completely different idea of somewhere else, but it turns out that, in practice, this capacity is under-utilized, if at all. Most websites are like simple motel rooms, with a central room leading to one or two other places, a few are like walk-through hotel suites, in which its possible to view everything in one route. Personally, I prefer web surfing to have the caprice of a Fellini film narrative in which the connection between the site first entered and the site ultimately exited is unpredictable, adventurous. Instead, the form of the website has largely become predictable: for composers, for example, there's an front, index, page and direct links from there to a biography (or cv, if the composer in question is an academic), a list of works, a press page, a small external links page, and a contact page. And that's it. For new musicians, we sure offer very little in the way of novelty, let alone surprise.

The late Edward Gorey's masterpiece among his many small books was The Raging Tide: Or, The Black Doll's Imbroglio (1987). The book has a stunning and disciplined composition, featuring characters associated with Gorey's unmade screenplay, among them the acrobatic Figbash, and is, in part, a response to surrealism by an artist who very much wanted to love surrealism but was too often disappointed. Each facing pair of pages in the book has an illustration to the right and a single sentence to the left. The sentences fall into two types: the first type has one or more characters performing an act with an object upon another character (or, in two cases, upon themselves)("Hooglyboo poured golden syrup over Naeelah."; "Figbash and Naeelah assaulted Hoogleyboo with cookie-cutters."), and the second is a simple declarative sentence ("Short sheets make the bed look longer."; "Not long ago they were destroyed by insects.") The narrative branches off at each page according to the reader's answer to a question like "If you dislike turnips less than you do prunes, turn to 22. If it is the reverse, turn to 21." or "If you want to persevere with the story, turn to 28. If you wish to correct a possible discrepancy, turn to 21." Thus, instead of a simple linear narrative, Gorey takes a trick from childrens' novelty books, and offers hundreds of possible ways of going through the book, thus guaranteeing that return visits to the book will be comfortably (or uncomfortably, as the case may be) within the same little universe, but never alike enough to be disappointing. Why can't more websites have that rhizome-like quality, with interesting things appearing via unpredictable routes?

(My own website is not good, let alone interesting; any links to model composer websites would be welcomes as well as any ideas or suggestions about how to do a better job.)

Websites, full of links internal, external, and infernal, were supposed to be the ideal medium from getting from some idea of here to some other idea of there and eventually to some completely different idea of somewhere else, but it turns out that, in practice, this capacity is under-utilized, if at all. Most websites are like simple motel rooms, with a central room leading to one or two other places, a few are like walk-through hotel suites, in which its possible to view everything in one route. Personally, I prefer web surfing to have the caprice of a Fellini film narrative in which the connection between the site first entered and the site ultimately exited is unpredictable, adventurous. Instead, the form of the website has largely become predictable: for composers, for example, there's an front, index, page and direct links from there to a biography (or cv, if the composer in question is an academic), a list of works, a press page, a small external links page, and a contact page. And that's it. For new musicians, we sure offer very little in the way of novelty, let alone surprise.

The late Edward Gorey's masterpiece among his many small books was The Raging Tide: Or, The Black Doll's Imbroglio (1987). The book has a stunning and disciplined composition, featuring characters associated with Gorey's unmade screenplay, among them the acrobatic Figbash, and is, in part, a response to surrealism by an artist who very much wanted to love surrealism but was too often disappointed. Each facing pair of pages in the book has an illustration to the right and a single sentence to the left. The sentences fall into two types: the first type has one or more characters performing an act with an object upon another character (or, in two cases, upon themselves)("Hooglyboo poured golden syrup over Naeelah."; "Figbash and Naeelah assaulted Hoogleyboo with cookie-cutters."), and the second is a simple declarative sentence ("Short sheets make the bed look longer."; "Not long ago they were destroyed by insects.") The narrative branches off at each page according to the reader's answer to a question like "If you dislike turnips less than you do prunes, turn to 22. If it is the reverse, turn to 21." or "If you want to persevere with the story, turn to 28. If you wish to correct a possible discrepancy, turn to 21." Thus, instead of a simple linear narrative, Gorey takes a trick from childrens' novelty books, and offers hundreds of possible ways of going through the book, thus guaranteeing that return visits to the book will be comfortably (or uncomfortably, as the case may be) within the same little universe, but never alike enough to be disappointing. Why can't more websites have that rhizome-like quality, with interesting things appearing via unpredictable routes?

(My own website is not good, let alone interesting; any links to model composer websites would be welcomes as well as any ideas or suggestions about how to do a better job.)

Sunday, May 04, 2008

Better Websites

The good thing about an active blog is that when it is fed enough interesting and new material some readers may actually feel invited to come back again, and sometimes at regular intervals: like a weekly date at a cafe or donuts and the daily newspaper (remember the daily paper? remember donuts?). Composers' websites, on the other hand, tend to be fixed points, sources of reference materials that one visits once and returns only in a programming emergency. There are a few dedicated composer websites out their with the professional panache to actually serve as a marketing tool, but they are rare. Those colleagues who have been able to combine a blog with their website, for some one-stop musical-philosophical shopping, seem to be on the right track.

As for myself, I'm not yet on the right track: my website is not good, being neither attractive enough to get by on looks alone nor interesting enough to get by on smarts and contents. The fact that my rights organization, GEMA, makes it all expensive to place sounds on the site is a major problem (although I have begun to do a better job of putting scores online). And this blog is, well, what it is, and I haven't even managed to make a proper back-up of all 866 (eight-hundred and sixty-six) (!) posts to-date. Ideally, Ithinks, I'd like to integrate website and blog into something more composerly, a piece in its own right, if you will, and one that rewards visiting and revisiting and -- hopefully -- more performances of my music. I'm somewhat encouraged in this idea by my current reading of Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves, which -- or so I'm told -- is a species of hyper-novel, and welcome news that experimental literature has not gone the way of the Dodo and the 20th century and the nickel cigar.

As for myself, I'm not yet on the right track: my website is not good, being neither attractive enough to get by on looks alone nor interesting enough to get by on smarts and contents. The fact that my rights organization, GEMA, makes it all expensive to place sounds on the site is a major problem (although I have begun to do a better job of putting scores online). And this blog is, well, what it is, and I haven't even managed to make a proper back-up of all 866 (eight-hundred and sixty-six) (!) posts to-date. Ideally, Ithinks, I'd like to integrate website and blog into something more composerly, a piece in its own right, if you will, and one that rewards visiting and revisiting and -- hopefully -- more performances of my music. I'm somewhat encouraged in this idea by my current reading of Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves, which -- or so I'm told -- is a species of hyper-novel, and welcome news that experimental literature has not gone the way of the Dodo and the 20th century and the nickel cigar.

Saturday, May 03, 2008

Luxury Time

I dislike wearing watches, but if someone were to make me a gift of this timepiece, which dispenses with seconds, minutes, and hours, distinguishing only night from day, and does so with all the precision a $300,000 dual Tourbillon swiss clockwork can bring to the task, I wouldn't be seen anywhere without it.

More slow listening

I recommend this interview with Christopher Fox, a composer whose musicality and intelligence I value highly. The money line is the last one:

It takes time to make people hear differently and for me that’s what a composer must do.

Friday, May 02, 2008

More Practical: Feldman

One large omission from the last post was the name of Morton Feldman. Feldman's notational practice was at once a very efficient means of achieving a form of ensemble complexity and paradoxical in its relationship between clarity of means and ambiguity of ends. Whether in the scores written on graph paper or the later works in which he drew all the barlines in advance of composing the music that would fill (or empty) those bars, he was setting up a rigid notational grid, the bars of which he could then proceed to dissolve, whether in terms of pitch (in the graph pieces) or time (in the later works).

I believe that one aspect of Feldman's musical sensibility was shared with the Skryabinistes,* if not inherited directly by Feldman via his piano teacher, Madame Press, who had been personally associated with Skryabin, and that is an emphasis on rubato, and a very broadly conceived rubato at that. But not only a rubato in terms of time, but also pitch (whether in the graph scores or in the later pieces with their finicky accidentals), and possibly, in the long works, with form.

In the later works, and especially the series of pieces for small ensemble (combinations of flutes, piano, percussion, often including celeste doubling) beginning with Why Patterns?), although the barlines go straight through the ensembles on the page, the individual measure in each individual line were often assigned different metres by Feldman thus erasing any simple vertical coordination. Feldman was able to work with vertical relationships on the page that would in turn be shattered and scattered, both back and forth, in the real time of a performance. The result is an ensemble texture that is polyphonic -- in the sense used by systematic musicology -- but not of an historic polyphonic sensibility, and -- again like Skryabin, who beat Schoenberg to this -- a tonal practice in which vertical and horizontal distinctions are unclear if not entirely irrelevant.

_____

* Skyrabin's is a ghost-like presence and influence over much later 20th century music. Three important Skryabinistes who emigrated to France were Arthur-Vincent Lourié, Nicolay Oboukhov and Ivan Wïschnegradsky. Lourié is considered the first musical futurist, and after his departure from the Soviet Union, would make connections to Busoni and Stravinsky. Oboukhov, almost unknown, was a decided mystic, developed an idiosynchratic tonal system which, at least in part, was based upon a non-serial manipulation of twelve tone sets, composed for a Theremin-like electronic instrument, "La Croix Sonore, and devoted most of his energies to a large orchestral and vocal work titled The Book of Life. Wischnegradsky's contacts with Messiaen and Boulez -- largely written out of eithers' biographies, like the quartertones in Boulez's original version of Le Visage Nuptial -- deserve more attention.

I believe that one aspect of Feldman's musical sensibility was shared with the Skryabinistes,* if not inherited directly by Feldman via his piano teacher, Madame Press, who had been personally associated with Skryabin, and that is an emphasis on rubato, and a very broadly conceived rubato at that. But not only a rubato in terms of time, but also pitch (whether in the graph scores or in the later pieces with their finicky accidentals), and possibly, in the long works, with form.

In the later works, and especially the series of pieces for small ensemble (combinations of flutes, piano, percussion, often including celeste doubling) beginning with Why Patterns?), although the barlines go straight through the ensembles on the page, the individual measure in each individual line were often assigned different metres by Feldman thus erasing any simple vertical coordination. Feldman was able to work with vertical relationships on the page that would in turn be shattered and scattered, both back and forth, in the real time of a performance. The result is an ensemble texture that is polyphonic -- in the sense used by systematic musicology -- but not of an historic polyphonic sensibility, and -- again like Skryabin, who beat Schoenberg to this -- a tonal practice in which vertical and horizontal distinctions are unclear if not entirely irrelevant.

_____

* Skyrabin's is a ghost-like presence and influence over much later 20th century music. Three important Skryabinistes who emigrated to France were Arthur-Vincent Lourié, Nicolay Oboukhov and Ivan Wïschnegradsky. Lourié is considered the first musical futurist, and after his departure from the Soviet Union, would make connections to Busoni and Stravinsky. Oboukhov, almost unknown, was a decided mystic, developed an idiosynchratic tonal system which, at least in part, was based upon a non-serial manipulation of twelve tone sets, composed for a Theremin-like electronic instrument, "La Croix Sonore, and devoted most of his energies to a large orchestral and vocal work titled The Book of Life. Wischnegradsky's contacts with Messiaen and Boulez -- largely written out of eithers' biographies, like the quartertones in Boulez's original version of Le Visage Nuptial -- deserve more attention.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)