On balance, it's probably better to be a practical composer. Everything else being equal, a more practical score will encourage more players and concert organizers, and a more practical working method will lead to less anxiety in the composing process. This isn't absolute, of course, as there will always be musicians who look for challenges, even the impossible -- virtuosity for its own sake -- and sometimes asking a musician to do more rather than less will actually encourage him or her to at least get the lesser part right. Moreover, there is (or at least should be) room for the idealists among us and, so long as no one gets bitter about well-intentioned but poorly realized or even unperformed works, we should be able to enjoy the luxury of impracticality.

Composers manifest their practicality in different ways. Harry Partch developed tablature-like notations for each of his instrumental innovations, so that players were instructed about the specific physical -- Partch would have said corporeal -- acts they were required to perform rather than confronted with a notation based upon abstract tonal relationships underlying his tuning practice. John Cage, with his mature works, never composed without a specific performer and performance in mind, and got each of his finished scores right off to his publisher. Henry Brant developed astonishingly efficient techniques for anxiety-free composition and performance of works with considerable complexity (see here). During the days when his ensemble was the main vehicle for his work, Philip Glass produced only the notation required by his own ensemble, often just parts with the minimum of markings and annotations, and not the time-consuming clean copied required by the traditional publish-and-then-perform system. And Iannis Xenakis, whose reputation was often mistakenly built around his book, Formalized Music (which, to be charitable, was a poorly edited mess), rather than his music, was in fact much less a theorist than a composer who was on the constant search for practical and efficient means of arriving at complex musical surfaces. The question of practicality is connected to that of complexity, but it is far from a simple parallel: practical means can lead to great complexity, while sometimes the simplest-seeming music is the product of considerable labor, cogitation, or just plain musicking.

A displaced Californian composer writes about music made for the long while & the world around that music. ~ The avant-garde is flexibility of mind. — John Cage ~ ...composition is only a very small thing, taken as a part of music as a whole, and it really shouldn't be separated from music making in general. — Douglas Leedy ~ My God, what has sound got to do with music! — Charles Ives

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

Long-Wave

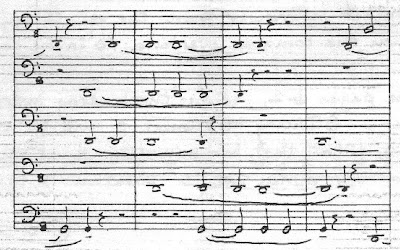

Often in the west coast radical music the focus is on the low and the slow, acoustic territory in which magic can readily happen. Here is the score (a big file, 3.6MB scan of the public domain ms. score) to the LONG-WAVE QUINTET of Bhisma Xenotechnites, for 3 contrabassi, bass tuba and contrabassoon, with gran casa. (The composer wrote to me: "To the question of Why six players in a quintet? I can only answer, Why four players in a Trio Sonata?".)

Often in the west coast radical music the focus is on the low and the slow, acoustic territory in which magic can readily happen. Here is the score (a big file, 3.6MB scan of the public domain ms. score) to the LONG-WAVE QUINTET of Bhisma Xenotechnites, for 3 contrabassi, bass tuba and contrabassoon, with gran casa. (The composer wrote to me: "To the question of Why six players in a quintet? I can only answer, Why four players in a Trio Sonata?".) Seven points to anyone who recognizes the source -- almost verbatim -- of the bass drum part.

I have placed some other scores by this composer online: a Piano Sonata, a String Quartet, and a set of Watergate Rounds.

Virtuosi and yet another new simplicity

Here's a concert-on-demand broadcast by the Quatour Bozzini, an ensemble to which attention ought be paid. The program is packaged as "new simplicity" by the CBC, which is okay, so long as a definite article isn't attached to the label ('cause then we'd have to argue all about all those past instances of The New Simplicity). There is music by my friends Markus Trunk and Tom Johnson, as well as Chris Newman and Matteo Fargion.

Actually, come to think of it, the names Johnson and Newman ought to immediately send up lots of warning signals about a simplicity label. Johnson's methodical rigor and clarity of means often arrives at a surface that is far from simple, and Newman's has always been a music about which I have no idea what to think, but I do know that simple is not the right word, as however raw, naive, mundane, or simplistic as the surface may appear, the net effect of listening to Newman's music is all-too-frequently a (welcome) challenge to everyday sensibility.

Actually, come to think of it, the names Johnson and Newman ought to immediately send up lots of warning signals about a simplicity label. Johnson's methodical rigor and clarity of means often arrives at a surface that is far from simple, and Newman's has always been a music about which I have no idea what to think, but I do know that simple is not the right word, as however raw, naive, mundane, or simplistic as the surface may appear, the net effect of listening to Newman's music is all-too-frequently a (welcome) challenge to everyday sensibility.

Monday, April 28, 2008

Rights

ASCAP is gathering signatures for a "Bill of Rights for Songwriters & Composers". While I'm generally sympathetic to the stated intent of the effort, it's east to recognize that this is largely a symbolic gesture, as the legal framework governing creative properties has increasingly been dictated by the largest corporate benefactors with their ample lobbying resources rather than individual artists, and that there are persistent and large questions about how an artist will be compensated in new media and new modes of transmission. Interestingly, as the "P" in "ASCAP" stands for publishers, the word publisher does not appear once in this petition, and the relationship between creative artists and publishers is not without tension at this time, especially when new technologies allow artists to bypass mediating forces -- both publishers and rights organizations, like ASCAP -- and interact, on a commercial basis, directly with audiences.

As a resident of Germany, I belong to GEMA, the local rights organization. GEMA has a de facto monopoly on collecting licenses here, and has done it extraordinarily well for a long time, but it is far from clear that GEMA has been able to adapt to new media in an appropriate way, nor is it clear that the traditional parity between "serious" and "entertainment" composers in terms of compensation will be sustained (in terms of representation, the parity has been dropped altogether). So my attention was aroused when I read article 7 of this proposed "Bill of Rights", which asserts that:

As a resident of Germany, I belong to GEMA, the local rights organization. GEMA has a de facto monopoly on collecting licenses here, and has done it extraordinarily well for a long time, but it is far from clear that GEMA has been able to adapt to new media in an appropriate way, nor is it clear that the traditional parity between "serious" and "entertainment" composers in terms of compensation will be sustained (in terms of representation, the parity has been dropped altogether). So my attention was aroused when I read article 7 of this proposed "Bill of Rights", which asserts that:

We have the right to choose the organizations we want to represent us and to join our voices together to protect our rights and negotiate for the value of our music.The present environment for the protection of musical copyrights is a confusing one. On the one hand, periods of protection have been extended by legislation into preposterously long durations, and copyright protection has been asserted for all known and potential media. On the other hand, this over-extension of protection does have real negative affects on keeping work in the public ear, and effective mechanisms for generating license fees from new media have not yet been designed, let alone implemented with anything other than caprice. I have had concerts and broadcasts cancelled by presenters reluctant to pay licenses, I must report each performance of my own work to GEMA in order to receive my licence, and if I wish to place recordings of my own work online, GEMA insists that I myself pay a license fee in advance. In other words, it's not yet a satisfactory state of affairs.

Sunday, April 27, 2008

Henry Brant

In memory of Henry Brant, here's an item, number 28 in my landmarks list, from September of last year:

Henry Brant: On the Nature of Things (After Lucretius) (1956)

Brant, 94 years old and still very much an active presence is perhaps our last direct connection back to the "ultra-modern" music of the early 20th century, which was silenced by the nationalism and realism (socialist, or otherwise; whatever realism was supposed to mean in music) that accompanied the Great Depression and Second World War. He was one of the youngest composers included in Henry Cowell's essay anthology American Composers on American Music.

Brant, an eminently practical musician, survived the eclipse of the ultra-modern era as a copyist, orchestrator, conductor, and performer (i.a. he was a virtuoso tin whistler) in radio, for Broadway stage, and for the films. Indeed, his high esteem as an orchestrator for films has continued well into recent years, with his work for the great film composer Alex North perhaps best known*, but -- if the imdb is to be believed -- Brant was not only responsible for orchestrating Virgil Thomson's two Pare Lorentz films -- The River and The Plough that Broke the Plains and the Pulitzer-prize winning score to Flaherty's Lousiana Story, he also assisted on the orchestration for Aaron Copland's score to The City. (Brant also worked, for decades, as a labor of love, on an orchestration of Ives' "Concord" Sonata.) The skills that Brant picked up doing commercial work, often in the most time-restricted circumstances, are skills that Brant has maintained throughout his career; in particular, he often introduces improvisation into scores in place of writing a part out in whole and, in advance of a major composition, he writes a "prose report" describing the project in enough detail to eliminate any anxieties that might enter during the composing process proper.

Brant is best-known, however, for his spatial works -- pieces in which the performing musicians and sound sources are strategically distributed through the performing space. Brant came to spatial music when he resumed writing in the musical spirit that had been cut short by the 1930's and 1940's, realizing that spatial separation was an ideal solution to projecting the kind of dissonant polyphony that he was after. He knew some significant earlier examples of spatial music -- Berlioz**, Gabrieli -- but it was in Ives, as especially the small gem The Unanswered Question, that he recognized the potential for space as a dimension for integrating and segregating streams of music.

On the Nature of Things shows Brant in an unusually gentle voice, and of his spatial works it requires only modest resources: strings, woodwind, a horn, a glockenspiel, placed alone or in groups discretely around the space of a conventional hall. A tone poem, lifted more-or-less intact from a work of operatic dimensions called The Grand Universal Circus, it is also unusual for Brandt -- who often revels in a more comic mode -- in the philosophical substance of its subject matter, a passage from Lucretius's ontological poem.

A recording of On the Nature of Things, by the Louisville Orchestra, issued in the 1950's is online here. It's a bit rough around the edges, with the spatial elements substantially flattened by the microphone; a new recording would be a fine thing. Incidentally, this is a piece I first encountered via a page of its score, published in Guillermo Espinoza's remarkable series Composers of the Americas/Compositores de las Americas. Brant's cheerful manuscript with its clear instructions for making the spatial placement work made a lasting impression.

_____

*If I had another day in the week, I'd write a long post about the Brant-orchestrated North score to 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was not used in the final cut.

** There are a couple of non-trivial connections between Brant and Berlioz. Berlioz played flute and flageolet, Brant plays flute and tin whistle, a cousin of the flageolet. Both practiced heterodox harmony and counterpoint. Berlioz and Brant explored the use of physical space in music and both were great orchestrators (which I intend as a real compliment), writing substantial texts on the subject. I have heard from Mr. Brant's assistant that his orchestration book, with the superb title Textures & Timbres, has just finished final edits this week and will be published next year by Carl Fischer.

Henry Brant: On the Nature of Things (After Lucretius) (1956)

Brant, 94 years old and still very much an active presence is perhaps our last direct connection back to the "ultra-modern" music of the early 20th century, which was silenced by the nationalism and realism (socialist, or otherwise; whatever realism was supposed to mean in music) that accompanied the Great Depression and Second World War. He was one of the youngest composers included in Henry Cowell's essay anthology American Composers on American Music.

Brant, an eminently practical musician, survived the eclipse of the ultra-modern era as a copyist, orchestrator, conductor, and performer (i.a. he was a virtuoso tin whistler) in radio, for Broadway stage, and for the films. Indeed, his high esteem as an orchestrator for films has continued well into recent years, with his work for the great film composer Alex North perhaps best known*, but -- if the imdb is to be believed -- Brant was not only responsible for orchestrating Virgil Thomson's two Pare Lorentz films -- The River and The Plough that Broke the Plains and the Pulitzer-prize winning score to Flaherty's Lousiana Story, he also assisted on the orchestration for Aaron Copland's score to The City. (Brant also worked, for decades, as a labor of love, on an orchestration of Ives' "Concord" Sonata.) The skills that Brant picked up doing commercial work, often in the most time-restricted circumstances, are skills that Brant has maintained throughout his career; in particular, he often introduces improvisation into scores in place of writing a part out in whole and, in advance of a major composition, he writes a "prose report" describing the project in enough detail to eliminate any anxieties that might enter during the composing process proper.

Brant is best-known, however, for his spatial works -- pieces in which the performing musicians and sound sources are strategically distributed through the performing space. Brant came to spatial music when he resumed writing in the musical spirit that had been cut short by the 1930's and 1940's, realizing that spatial separation was an ideal solution to projecting the kind of dissonant polyphony that he was after. He knew some significant earlier examples of spatial music -- Berlioz**, Gabrieli -- but it was in Ives, as especially the small gem The Unanswered Question, that he recognized the potential for space as a dimension for integrating and segregating streams of music.

On the Nature of Things shows Brant in an unusually gentle voice, and of his spatial works it requires only modest resources: strings, woodwind, a horn, a glockenspiel, placed alone or in groups discretely around the space of a conventional hall. A tone poem, lifted more-or-less intact from a work of operatic dimensions called The Grand Universal Circus, it is also unusual for Brandt -- who often revels in a more comic mode -- in the philosophical substance of its subject matter, a passage from Lucretius's ontological poem.

A recording of On the Nature of Things, by the Louisville Orchestra, issued in the 1950's is online here. It's a bit rough around the edges, with the spatial elements substantially flattened by the microphone; a new recording would be a fine thing. Incidentally, this is a piece I first encountered via a page of its score, published in Guillermo Espinoza's remarkable series Composers of the Americas/Compositores de las Americas. Brant's cheerful manuscript with its clear instructions for making the spatial placement work made a lasting impression.

_____

*If I had another day in the week, I'd write a long post about the Brant-orchestrated North score to 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was not used in the final cut.

** There are a couple of non-trivial connections between Brant and Berlioz. Berlioz played flute and flageolet, Brant plays flute and tin whistle, a cousin of the flageolet. Both practiced heterodox harmony and counterpoint. Berlioz and Brant explored the use of physical space in music and both were great orchestrators (which I intend as a real compliment), writing substantial texts on the subject. I have heard from Mr. Brant's assistant that his orchestration book, with the superb title Textures & Timbres, has just finished final edits this week and will be published next year by Carl Fischer.

Friday, April 25, 2008

These Galant Days

I really like this trailer for Paul Bailey's new work, requiem for a high crime enclave. The composer's description: it's "a deconstruction of Purcell's Funeral Music for Queen Mary (1694) based on excerpts from the from the LA Times Homicide Report which documents every murder that takes place in Los Angeles County using blog posts, comments, and Google Maps."

There is a lot of anxiety-free engagement with early music in new music these days, whether from folks like Bailey, Lloyd Rodgers or Jon Brenner on the US west coast or Nico Muhly on the east (or even some bits of mine, coastless as I be, here, here, & here). I, like my west coast colleagues, prefer forms with repeating elements, grounds especially (Mr Brenner likes chaconnes, I like passacaglias), and this activity connects happily with work by experimentalists ranging from Michael Nyman to Douglas Leedy (see this).

There is a lot of anxiety-free engagement with early music in new music these days, whether from folks like Bailey, Lloyd Rodgers or Jon Brenner on the US west coast or Nico Muhly on the east (or even some bits of mine, coastless as I be, here, here, & here). I, like my west coast colleagues, prefer forms with repeating elements, grounds especially (Mr Brenner likes chaconnes, I like passacaglias), and this activity connects happily with work by experimentalists ranging from Michael Nyman to Douglas Leedy (see this).

Concentrate

A trip to New Mexico is always an opportunity to stock up on Green Chile powder. I thought I had, but greedily managed to get through my supply in less than two weeks. So I tried to make some myself, using some Turkish peppers that looked and tasted very close enough to the New Mexican species. I started with a bit more than a pound, and after grilling the outer skins off, stemming them, drying in a low, fanned oven for several hours, and grinding to an optimal mix of powder and flakes, I was left with about an ounce and a half and a kitchen with a light cloud of capsaicin dust, but it is an ounce and a half of intensity and considerable character. (That 16:1 ratio of concentration is still nothing compared to the 40:1 of maple, or 80:1 of birch syrup).

Let me propose the following: The best music is something like that green chili powder: yes, there is the immediate sensation of the chili, much of it in the heat, or more precisely in the placement and timing of that heat (the best chiles or moles or adobos combine a variety of chiles so that one experiences a sequence of shocks at different places along the tongue and palate), but there is also a mix of bitter, sour, sweet, and perhaps umami that make the chili into a rather complete experience. In all the music I like, it is that combination of intensity and depth that draws me in again'n'again.

In music, we get our concentrates at both extremes of duration: the tiny gems of a Webern or Kurtag, or the vast expanses of La Monte Young or late Morton Feldman. But any music that invites the listener to engage more, to concentrate on detail as well as larger form, is certainly doing something right.

Let me propose the following: The best music is something like that green chili powder: yes, there is the immediate sensation of the chili, much of it in the heat, or more precisely in the placement and timing of that heat (the best chiles or moles or adobos combine a variety of chiles so that one experiences a sequence of shocks at different places along the tongue and palate), but there is also a mix of bitter, sour, sweet, and perhaps umami that make the chili into a rather complete experience. In all the music I like, it is that combination of intensity and depth that draws me in again'n'again.

In music, we get our concentrates at both extremes of duration: the tiny gems of a Webern or Kurtag, or the vast expanses of La Monte Young or late Morton Feldman. But any music that invites the listener to engage more, to concentrate on detail as well as larger form, is certainly doing something right.

Nachlaß

Dmitri Nabokov has announced that he will not destroy the unfinished manuscript (a collection of 50 index cards) of his father, Vladimir Nabokov's last work, The Original of Laura, thus violating the author's own instructions. This decision is naturally welcomed by all of us who continue to greet Max Brod's decision not to destroy the manuscripts of Franz Kafka's works. But it is not a consensus opinion: many do think that final requests by artists should be honored and the theoretical debts of an estate to an artist to "the world" or to "humanity" often fail to balance with the injury or neglect suffered by that artist, while alive, due to "the world" or "humanity".

*****

The estimable Frank J. Oteri writes about become executor of the musical works of an impressively prolific, but little-known, composer, Gabriel von Wayditch, and the comments to his article share some similar stories of other composers. Oteri raises the question: "What force would drive someone to create such a vast body of work without any opportunities, either financial or promotional?" But isn't the more important question: "If you believe in your work, what possible force could stop you from producing it?"

*****

Starting in High School, I made a serious study of the scores of Harry Partch, transcribing the better part of them by hand into my own analytical notation. I was fortunate because a few friends of Partch had endeavored, after his death, to make copies of all of his Ozalids, and I had access to the sets owned by Ervin Wilson and Lou Harrison. The Partch estate itself was unhelpful with this and has since entrusted the scores to a major traditional publisher, which has not yet, even after several years holding the scores, been able to publish the scores as anything other than rentals of manuscript copies, thus, in a real way, making the scores even more inaccessible today and, in the end, discouraging rather than encouraging more performance and study of Partch's work.

*****

The estimable Frank J. Oteri writes about become executor of the musical works of an impressively prolific, but little-known, composer, Gabriel von Wayditch, and the comments to his article share some similar stories of other composers. Oteri raises the question: "What force would drive someone to create such a vast body of work without any opportunities, either financial or promotional?" But isn't the more important question: "If you believe in your work, what possible force could stop you from producing it?"

*****

Starting in High School, I made a serious study of the scores of Harry Partch, transcribing the better part of them by hand into my own analytical notation. I was fortunate because a few friends of Partch had endeavored, after his death, to make copies of all of his Ozalids, and I had access to the sets owned by Ervin Wilson and Lou Harrison. The Partch estate itself was unhelpful with this and has since entrusted the scores to a major traditional publisher, which has not yet, even after several years holding the scores, been able to publish the scores as anything other than rentals of manuscript copies, thus, in a real way, making the scores even more inaccessible today and, in the end, discouraging rather than encouraging more performance and study of Partch's work.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Love as a continuity error

Readers of these pages must know by now that I'm obsessed with the issue of continuity in music, an obsession probably originating in my Southern Californian youth (where the continuity specialist is a perfectly ordinary member of a film crew), but made rather more articulate by experiencing the "cuing" pieces of Christian Wolff, in which a score may often be, in essence, a series of instructions for arriving at a continuity through attention to successions and simultaneities.

More articulate, but not yet articulate enough.

And now, once again, filmmaker Erroll Morris arrives on the scene, or rather in his blog, Zoom, with some spectacularly articulate ideas about re-enactments (something profoundly interesting to musicians), continuity and our perception of continuity. The discussion of Buñuel's use of two actresses to play the same role in That Obscure Object of Desire is just great, culminating in Morris's bittersweet speculative sentence: "Perhaps Buñuel sees love as a series of continuity errors?"

(A map of the entrances and exits of the two actresses in Buñuel's film, and the time separating their entrances, could be usefully construed as something a series of late Cagian time brackets, but with the duration of the brackets and the intervals between them becoming evermore shorter, so that eventually one actress leaves and the second almost immediately re-enters. I've always wished that Cage had begun to apply time deformations* of this sort more systematically in his "number" pieces, as the richness of these pieces lay largely in their formal invention, and such tempo changes would have made this quality even more intense.)

_____

* in this case, an accellerando, but it could have been just as interesting with a ritardando, or any of the other possible tempo-deforming shapes. Time deformation, by the way, is a term I steal, cheerfully, from Ron Kuivila and David Anderson's program, Formula ("FORth MUsic LAnguage"), one of the profoundly smart things to come out of 1980's electronic music.

More articulate, but not yet articulate enough.

And now, once again, filmmaker Erroll Morris arrives on the scene, or rather in his blog, Zoom, with some spectacularly articulate ideas about re-enactments (something profoundly interesting to musicians), continuity and our perception of continuity. The discussion of Buñuel's use of two actresses to play the same role in That Obscure Object of Desire is just great, culminating in Morris's bittersweet speculative sentence: "Perhaps Buñuel sees love as a series of continuity errors?"

(A map of the entrances and exits of the two actresses in Buñuel's film, and the time separating their entrances, could be usefully construed as something a series of late Cagian time brackets, but with the duration of the brackets and the intervals between them becoming evermore shorter, so that eventually one actress leaves and the second almost immediately re-enters. I've always wished that Cage had begun to apply time deformations* of this sort more systematically in his "number" pieces, as the richness of these pieces lay largely in their formal invention, and such tempo changes would have made this quality even more intense.)

_____

* in this case, an accellerando, but it could have been just as interesting with a ritardando, or any of the other possible tempo-deforming shapes. Time deformation, by the way, is a term I steal, cheerfully, from Ron Kuivila and David Anderson's program, Formula ("FORth MUsic LAnguage"), one of the profoundly smart things to come out of 1980's electronic music.

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

Sincere Forms

When I encounter a great performance, and particularly in two sensory domains, cooking and composing, my first reaction is often that of an intense desire to recreate the performance myself, to prolong and intensify the experience, but also to figure out how it was done, and greedily incorporate it into my own repertoire.

So figuring out how that chile relleno was made in Albuquerque or that Jamaican-style beef patty in Hartford or trying to recreate the cinnamon bread from my uncle's bakery in Morro Bay represent impulses as basic to this musician as learning canon and fugue. Getting the flavors right in larb or a Franconian Schäufele is like figuring out how a great and envied orchestrator doubled his woodwinds.

On more than one occasion a technique gathered in the kitchen has wandered into a piece of music (e.g. croissants and their 55 layers) but I have yet to observe a musical skill invading my cooking in a major way. But who knows? -- the application of chance operations to recipes may well be the next good thing. It would certainly be a way 'round the habits of taste.

So figuring out how that chile relleno was made in Albuquerque or that Jamaican-style beef patty in Hartford or trying to recreate the cinnamon bread from my uncle's bakery in Morro Bay represent impulses as basic to this musician as learning canon and fugue. Getting the flavors right in larb or a Franconian Schäufele is like figuring out how a great and envied orchestrator doubled his woodwinds.

On more than one occasion a technique gathered in the kitchen has wandered into a piece of music (e.g. croissants and their 55 layers) but I have yet to observe a musical skill invading my cooking in a major way. But who knows? -- the application of chance operations to recipes may well be the next good thing. It would certainly be a way 'round the habits of taste.

Monday, April 21, 2008

Be Galant

For some reason, I get asked a lot to recommend textbooks for composition. I've compiled a list of books that have been useful to me, personally, as a composer, but that list doesn't include much in the way of common practice western repertoire except for Morley's Plaine and Easy Introduction (which is a bit too early music-ish for most) and de la Motte's extraordinary Kontrapunkt (which is too German for many anglophones). I like both the Morley and the de la Motte as they are built around real repertoire of really great music and they cover a number of areas not featured in conventional instruction: Morley, for example, the rhythmic system, and de la Motte for going into depth on Josquin rather than Palestrina, a really good move, as well as going back to Notre Dame polyphony and forward to Wagner's network technique.

But now there's a superb book in English to recommend: Robert O. Gjerdingen's Music in the Galant Style. While this is boxed as a musicological essay, it's really a composition handbook for composing with the VARIOUS SCHEMATA common to a style widely used in the period you probably called the late baroque and early classic back in school ("baroque" and "classic" as terms identifying their musical practice would have been unknown to the composers concerned). Schemata are snippets of music, figure, patterns, routines, or formulae, many of them named, that appear pretty much intact on the surface of a piece of music and are re-encountered again and again in the real repertoire. As Gjerdingen wisely points out, the use of these schemata are precisely analogous to the use of lazzi in Commedia dell'Arte or of figures in modern figure skating. (One of the musical schemata is the Monte, which immediately made me think of routines in card tricks, another performing craft with an elaborate body of self-referential tropes that can be recombined and reworked into countless new compositions).

There are many ways, indeed an undetermined number of ways, of achieving a particular musical surface, a score. In general, in the academy, we have come round to teaching the composition of tonal music as a matter that begins with an abstraction -- i.e. a harmonic progression or, more fashionably, a tonal structure that is prolonged and given detail through processes that can be loosely grouped together under the term diminution -- rather than the assembly of concrete bits of musical material. Of course, this has never been the case in the teaching of vernacular musics, Jazz in particular, where training is closely associated with the acquisition of an ever-larger personal catalogue of possible chords, scales, and riffs, and there have been a number of heterodox theoretical projects: David Cope's experiments, for example, have coalesced into a study of how bodies of musical surface "signatures" can be recombined to replicate compositions in the style of a given work, composer, or repertoire. One is struck, however, by one contrast in these two styles of theory instruction and that is the degree of intimacy between the theory-making and a particular body of music.

In learning music, we need to go both broad and deep. There is a place an expansive and abstract theory-making, as this is how repertoires are fruitfully connected and this is where many new musical ideas are cooked up. As a composer, it's obvious, but for performers and listeners, it's essential, as it is a way of connecting with unknown musics. But there is also a place for depth, and this -- again, largely outside of vernacular music instruction -- is a real and present deficit in contemporary teaching. I can easily imagine a semester spent productively with Josquin and de la Motte, or now, with Gjerdingen and the masters of the Galant. Although the galant style, with its easily recognizeable body of schemata recommends itself well to such in-depth training, in a real way, it is all the same what repertoire is chosen, just so long as young musicians get the experience of a close encounter with a real music. *

Moreover, the Gjerdingen book is both scholarly and fun. I can't wait to try composing in sequences of Montes, Pontes, and Fontes, or Romanescas, Fenarolis, and Sol-Fa-Mi's. Get the book!

_____

* I don't have the fluency with the Galant that a longer study of the Gjerdingen would provide, but I have had the pleasure of singing and playing Central Javanese music, a repertoire in which schemata -- if I can borrow the term -- are shared by text, vocal melody, instrumental compsition, dance, and puppet movement. Amazing stuff.

But now there's a superb book in English to recommend: Robert O. Gjerdingen's Music in the Galant Style. While this is boxed as a musicological essay, it's really a composition handbook for composing with the VARIOUS SCHEMATA common to a style widely used in the period you probably called the late baroque and early classic back in school ("baroque" and "classic" as terms identifying their musical practice would have been unknown to the composers concerned). Schemata are snippets of music, figure, patterns, routines, or formulae, many of them named, that appear pretty much intact on the surface of a piece of music and are re-encountered again and again in the real repertoire. As Gjerdingen wisely points out, the use of these schemata are precisely analogous to the use of lazzi in Commedia dell'Arte or of figures in modern figure skating. (One of the musical schemata is the Monte, which immediately made me think of routines in card tricks, another performing craft with an elaborate body of self-referential tropes that can be recombined and reworked into countless new compositions).

There are many ways, indeed an undetermined number of ways, of achieving a particular musical surface, a score. In general, in the academy, we have come round to teaching the composition of tonal music as a matter that begins with an abstraction -- i.e. a harmonic progression or, more fashionably, a tonal structure that is prolonged and given detail through processes that can be loosely grouped together under the term diminution -- rather than the assembly of concrete bits of musical material. Of course, this has never been the case in the teaching of vernacular musics, Jazz in particular, where training is closely associated with the acquisition of an ever-larger personal catalogue of possible chords, scales, and riffs, and there have been a number of heterodox theoretical projects: David Cope's experiments, for example, have coalesced into a study of how bodies of musical surface "signatures" can be recombined to replicate compositions in the style of a given work, composer, or repertoire. One is struck, however, by one contrast in these two styles of theory instruction and that is the degree of intimacy between the theory-making and a particular body of music.

In learning music, we need to go both broad and deep. There is a place an expansive and abstract theory-making, as this is how repertoires are fruitfully connected and this is where many new musical ideas are cooked up. As a composer, it's obvious, but for performers and listeners, it's essential, as it is a way of connecting with unknown musics. But there is also a place for depth, and this -- again, largely outside of vernacular music instruction -- is a real and present deficit in contemporary teaching. I can easily imagine a semester spent productively with Josquin and de la Motte, or now, with Gjerdingen and the masters of the Galant. Although the galant style, with its easily recognizeable body of schemata recommends itself well to such in-depth training, in a real way, it is all the same what repertoire is chosen, just so long as young musicians get the experience of a close encounter with a real music. *

Moreover, the Gjerdingen book is both scholarly and fun. I can't wait to try composing in sequences of Montes, Pontes, and Fontes, or Romanescas, Fenarolis, and Sol-Fa-Mi's. Get the book!

_____

* I don't have the fluency with the Galant that a longer study of the Gjerdingen would provide, but I have had the pleasure of singing and playing Central Javanese music, a repertoire in which schemata -- if I can borrow the term -- are shared by text, vocal melody, instrumental compsition, dance, and puppet movement. Amazing stuff.

Sunday, April 20, 2008

The Oracle has spoken

My bs-meter is usually highly sensitive to claims of the prophetic, whether biblical or astrological, read from palms, tea leaves, or yaro sticks, or discerned from Kondratyev waves. But now, and for the record, I wish to report that I've been completely convinced by the oracle at Amazon.com, which now predicts, based on my past buying habits, that I would be interested in purchasing Things to Do Now That You're Retired by Jane Garton. Well, if the oracle says that I'm retired, I must be retired.* It was a good career, however brief and however modest, and now -- without the advice of Ms. Garton, mind you -- I shall dedicate my reclining years to good living and the occasional composition of a few choice Peches de vieillesse.

_____

* Which reminds me of a story.... sometime in his later tenure at Harvard, Walter Piston was asked by his students about his retirement plans. He is reported to have replied, in his deepest Maine accent, "Why, I've been retired for years."

_____

* Which reminds me of a story.... sometime in his later tenure at Harvard, Walter Piston was asked by his students about his retirement plans. He is reported to have replied, in his deepest Maine accent, "Why, I've been retired for years."

Referees

A performer or composer gets a review from a newspaper critic. A musicologist or theorist gets an article published in a referree'd music journal. A composer or a musicologist gets a score or an edition published by a house with a substantial reputation. While there have certainly been cases of compromised, if not corrupt, reviewers, journal editors, or publishers, by and large, these institutional arrangements did a reasonably good job of providing at least one channel for the evaluation of a musician or scholar's work, and often this evaluation would become a permanent part of a bio or cv, which in turn became part of a performer's press package or an academic's tenure and promotion file. All of these institutions are in transition at the moment: newspapers publish fewer reviews, if they publish any, journals are notoriously slow to publish and face competition from other media, and traditional publishing has largely been subsumed by the broader commercial field of rights management, in which serious music plays an ever more insignificant role. In part, web-based media (including journals, music publishing, and yes, Virginia, blogging) have taken on many of these functions, but have institutions in professional concert management or academe recognized these changes? Does a composer still need to be published by B&H or Schott? Can a performer include online review in his or her promo materials? Can an academic get tenure with a non-referee'd, but oft-read-and-discussed online article?

It has been often objected that bloggers are self-appointed and lack the qualifications of independent referees. However, traditional publishers and concert managers and musicological authorities rose to their positions through market (or, at least, market-like) forces, and similar forces appear to be at work online. Any of the lists of the most-read blogs, for example, will reveal that the tops of the lists have gelled around writers with significant professional qualifications or experiences, including those writers who identify themselves simply as music-loving amateurs. Moreover, the incorporation of comments into blogs expands the content and context of the information and opinions in the blog, further assisting in the critical reading of a blogged opinion. I wrote here before:

It has been often objected that bloggers are self-appointed and lack the qualifications of independent referees. However, traditional publishers and concert managers and musicological authorities rose to their positions through market (or, at least, market-like) forces, and similar forces appear to be at work online. Any of the lists of the most-read blogs, for example, will reveal that the tops of the lists have gelled around writers with significant professional qualifications or experiences, including those writers who identify themselves simply as music-loving amateurs. Moreover, the incorporation of comments into blogs expands the content and context of the information and opinions in the blog, further assisting in the critical reading of a blogged opinion. I wrote here before:

"In other words, in order to read a piece of criticism, you have to read critically. Basta."I believe that the one of the most important changes in these institutional structures is that participants in institutional systems must become far less passive consumers of information when using it to evaluate the work of their colleagues. This may well entail reading the information in greater depth, following its own argument, and not immediately assuming that information received from traditionally esteemed channels should automatically share that esteem. There are some small signs that music managers have begun to recognize and even solicit online opinions of artists, taking advantage of the rapid, cost-effective, permanent, and viral presence of online opinion. Academia is somewhat slower: a posting on the un-referee'd alternative tuning list with hundreds of follow-ups may well represent a more serious, timely, and productive bit of music theory than an article in Teh Journal of Music Theory but, as far as I can tell, only the JMT article is going to help with tenure at Podunk U..

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Spring, in an album, is coming

A SPRING ALBUM -- a collection of small pieces for percussion, in solos or small ensemble, has now started to assemble itself. This is the follow-up to the online A WINTER ALBUM (which I host here) of small piano pieces. The goal of these projects is to keep a small repertoire of playable pieces online, a marker of the presence and liveliness of the new music, all done without the intervention of a formal, institutional publishing structure. The deadline is the first of May. Send pdfs, with your own copyright on the score, to me at djwolf(AT-SIGN)snafu.de.

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

Drafting

Since moving to computer-based notation, and often composing directly into the notation program, my drafting process has become more continuous and less defined by the discrete steps of doing work all by hand. All of those steps -- from sketch to draft to clean pencil copy to inked manuscript -- have become condensed into a single, perpetually mutating, data file. Some composers like to save all of their in-between steps even when composing in digital formats; I can't quite bring myself to do that. In fact, erasing all those steps and missteps has become program for me: I want to forget those steps myself and erase them from public memory in one move, if only to lend a bit more magic to the finished product.

Here's a far-too-vivid description of a novelist's drafting process, from an interview with China Miéville:

Here's a far-too-vivid description of a novelist's drafting process, from an interview with China Miéville:

CM: Yes, I'm finishing a novel right now. I've finished the first draft. An analogy occurred to me, as I stared at this beautiful, fucking messy thing. When a cat gives birth to a kitten, it then licks all the manky crap off it for an hour. So the transition from first to second draft: I have to spend a month licking afterbirth off a kitten.For a precious few of us, our sketches and manuscripts will eventually be sought after by collectors or archives (for new music, the most prestigious archive has been this one). For the rest of us, it's all about the practical issues of living with the mess and figuring out what to do with it when we're done. By moving to composition directly into the computer, I will cheerfully admit to making it difficult for future musicologists to trace my steps and less cheerfully admit that I am separating myself from at least a tiny chance of someday generating income from the sale of manuscripts. I have kept my manuscript juvenalia, but even with that, there have been moments in which I have almost convinced myself to reduce all my files to finished and digitized scores and to barbecue the remaining paperwork, but the moment has never lasted long enough to turn into concrete action. So I still have a small stack of paper manuscripts as an emblem of my antiquity and will otherwise continue to work without leaving any of that manky stuff behind.

JP: That's a great analogy.

CM: I thought so. Thank you. It's hideously accurate-feeling.

Monday, April 14, 2008

More on China

Scott Spiegelberg has a thoughtful response to my postings on response to Chinese internet censorship and Tibet policy. Let me make it clear that I have no problem with the Olympic Games going forward, but I think we should not bother watching the broadcasts of the Games. As China censors so much information going into their country why should we be expected to consume the officially sanctioned information coming out of the country? This form of protest seems measured and if another country, including the US, was similarly censoring incoming information, I would avoid officially sanctioned information from that country as well. The free exchange of information is a basic and universal civil right, and I believe that acquiescence to China on this point (as is done, for example, by several western commercial search engines) is implicitly saying that the people of China are somehow less entitled to this right than the citizens of other states.

Others take an even harder stand: on the Tibet issue, Philip Glass advocates a boycott of the games altogether.

Others take an even harder stand: on the Tibet issue, Philip Glass advocates a boycott of the games altogether.

Pre-Concert Triage

So you arrive for a brief final rehearsal of your piece just before the concert and things do not go well. What are you going to do? It could have just been a bad rehearsal. It happens. It could have been the only rehearsal. It happens. It could have been your piece. It happens.

There will be time later to establish precisely what happened and try to find a permanent fix, but it doesn't matter now: you have to take responsibility for your piece and have to decide quickly whether to go on with the performance or not, and if you go on, you have to determine if there is at least something that can be corrected or improved before the performance.

If you are the composer, you are in your rights to withdraw the piece if you feel either the composition has failed or the organizers and/or performers have given insufficient rehearsal. This has to be balanced against the interests of an audience which has expanded time, energy, and perhaps some money in coming to the concert as well as against your -- always diplomatic -- relationship to the musicians and/or organizers. What, precisely, to announce publicly about a withdrawn piece is also a diplomatic matter. I have heard composers or organizers announce that a piece has been withdrawn due to insufficient rehearsal or lack of resources but, for whatever reason, I have yet to hear a composer announce the withdrawal of a piece from a concert due to unsatisfactory composition. (Composers do withdraw -- whether to revise or to bury -- pieces from our catalogs with some frequency, however).

An interesting compromise was offered once by Lou Harrison, who let an underprepared performance go on, but announced from the stage that it was a rehearsal and not a performance. The audience, players, and the composer were satisfied with this and the rehearsal, as it turns out, went splendidly.

If you do decide to let a piece go forward, my experience has been that it's very useful to choose one global feature of the piece for all of the players to focus upon, and allow the remaining aspects of the performance to hang onto the coattails of that feature. This feature could be simply establishing some landmarks or signs to make sure that no one gets lost, or taking tempi up or down a notch, or an agreement about dynamic levels, or fine-tuning initial and final chords a bit (hint: in major triads, either get the major third a bit narrower, or allow the third to fade out faster than the tonic and fifth; in ensemble with piano or other equal tempered instruments, drop the third from all but the initial attack in sustained sounds).

What I have personally found that works well is to get ensembles to play attacks and releases with greater accuracy and to play with conviction regardless of errors. A ensemble sound with a sharp beginning, a committed sustain, and a sharp ending will do wonders for an overall performance, no matter precisely which sounds are played. At least a suggestion of polish will be lent to the performance as well as your piece.

Sometimes, I've found it useful or necessary to communicate directly with individual members of a ensemble before a performance. This is often just to encourage them over some matter that has clearly been discouraging. This is best done privately and discretely and finding the right mix of praise and suggestion is a question of sensitivity and, to be honest, not all composers are all that sensitive. But rest assured, the moment directly before a concert is one for confidence building and not one for brutal critique.

Finally, you can change your piece. If you're the composer, you can change any of your pieces until the moment you, personally, start decomposing. If you are performing the piece yourself, you have license to change it during a performance, even if your "revisions" would sound like "errors" when played by anyone else. If others are performing, you can allow them to drop sections or movements that are not working or you can simplify things -- dropping notes into more comfortable octaves, for example. You can even muck things up a bit more, adding noises and notes, if that's the desired effect. As Morton Feldman would have put it, you can always add that cowbell. I am fairly brutal about my own pieces, but I can usually recognize that there is still some distance that can be taken with last-minute modifications to a score before one gives it up entirely.

There will be time later to establish precisely what happened and try to find a permanent fix, but it doesn't matter now: you have to take responsibility for your piece and have to decide quickly whether to go on with the performance or not, and if you go on, you have to determine if there is at least something that can be corrected or improved before the performance.

If you are the composer, you are in your rights to withdraw the piece if you feel either the composition has failed or the organizers and/or performers have given insufficient rehearsal. This has to be balanced against the interests of an audience which has expanded time, energy, and perhaps some money in coming to the concert as well as against your -- always diplomatic -- relationship to the musicians and/or organizers. What, precisely, to announce publicly about a withdrawn piece is also a diplomatic matter. I have heard composers or organizers announce that a piece has been withdrawn due to insufficient rehearsal or lack of resources but, for whatever reason, I have yet to hear a composer announce the withdrawal of a piece from a concert due to unsatisfactory composition. (Composers do withdraw -- whether to revise or to bury -- pieces from our catalogs with some frequency, however).

An interesting compromise was offered once by Lou Harrison, who let an underprepared performance go on, but announced from the stage that it was a rehearsal and not a performance. The audience, players, and the composer were satisfied with this and the rehearsal, as it turns out, went splendidly.

If you do decide to let a piece go forward, my experience has been that it's very useful to choose one global feature of the piece for all of the players to focus upon, and allow the remaining aspects of the performance to hang onto the coattails of that feature. This feature could be simply establishing some landmarks or signs to make sure that no one gets lost, or taking tempi up or down a notch, or an agreement about dynamic levels, or fine-tuning initial and final chords a bit (hint: in major triads, either get the major third a bit narrower, or allow the third to fade out faster than the tonic and fifth; in ensemble with piano or other equal tempered instruments, drop the third from all but the initial attack in sustained sounds).

What I have personally found that works well is to get ensembles to play attacks and releases with greater accuracy and to play with conviction regardless of errors. A ensemble sound with a sharp beginning, a committed sustain, and a sharp ending will do wonders for an overall performance, no matter precisely which sounds are played. At least a suggestion of polish will be lent to the performance as well as your piece.

Sometimes, I've found it useful or necessary to communicate directly with individual members of a ensemble before a performance. This is often just to encourage them over some matter that has clearly been discouraging. This is best done privately and discretely and finding the right mix of praise and suggestion is a question of sensitivity and, to be honest, not all composers are all that sensitive. But rest assured, the moment directly before a concert is one for confidence building and not one for brutal critique.

Finally, you can change your piece. If you're the composer, you can change any of your pieces until the moment you, personally, start decomposing. If you are performing the piece yourself, you have license to change it during a performance, even if your "revisions" would sound like "errors" when played by anyone else. If others are performing, you can allow them to drop sections or movements that are not working or you can simplify things -- dropping notes into more comfortable octaves, for example. You can even muck things up a bit more, adding noises and notes, if that's the desired effect. As Morton Feldman would have put it, you can always add that cowbell. I am fairly brutal about my own pieces, but I can usually recognize that there is still some distance that can be taken with last-minute modifications to a score before one gives it up entirely.

Sunday, April 13, 2008

Old Publishing/New Publishing

An old topic on this blog has been the obsolescence of traditional music publishing for composers of new music. I believe that there is and will continue to be a niche role for traditional publishing houses, but only when,

(A) at a minimum, the publisher offers these three services:

(1) Promotion of the composers' work.

(2) Production and editing, at the publisher's own expense (and not charged against future royalties) of adequate scores, parts, and other performance materials for perusal, sale or rental.

(3) Management of the timely and convenient distribution, rental, and or sale of those materials, including internet distribution of materials in the form of electronic documents.

and

(B) the composer:

(1) doesn't have the time, patience, or desire to do any of the above.

(2) is willing to give up half their performance and mechanical royalties in return for the services.

(3) is willing to trust a publisher to provide the above services over a sustained period of time and in a fashion appropriate to the composer's own interests.

Traditional publishing does continue to carry a certain caché -- it is indeed cool to be able to claim the same publisher as Brahms or Stravinsky, and many a young academic composer facing a tenure decision will be told that they need to get one of their works printed by such a house. But that status has little or nothing to do with the actual tasks of getting music played and heard nowadays, and the current interests of traditional publishers have moved significantly beyond traditional practice.

Take, for example, the case of Boosey & Hawkes, one of the best old firms. In a press release dated Friday, we learn that B&H has been sold by its current owner, HgCapital, to IMAGEMMUSIC,* the music publishing fund of All Pensions Group (APG) and CP Masters BV. This is real success for HgCapital, which paid 75mGBP for B&H in 2003 and now sells it for 126mGBP. Moreover, we learn that, in the past four years, B&H has been significantly restructured, "executing a transformation of the business from a traditional classical music publisher into a 21st century music rights group", and that it has "outsourced a number of non-core activities such as printing and distribution and developed a series of new revenue streams. In particular it has developed a strong presence in the market for music in advertising and film, where revenues are currently growing at approximately 30% per annum." While it is likely that some composers will benefit from this restructuring, it is far from clear that this will be the case for the majority of classical composers, whose interests will necessarily be seen as even more minor within the context of an ever-larger concern.

The alternative is of course, self-publication, as a solo effort (the Stockhausen Verlag or Tom Johnson's Editions 75 are good examples) or in some cooperative arrangement with like-minded musicians (Frogpeak Music, Thürmchen Verlag, Material Press are some examples). The advantages are control over the services provided, retention of royalties by the composer, and direct communication between performers and composers with regard to materials and performances. Electronic publication of scores is a perfect fit both for self-publication and for a musical world in which prospective players want materials now, if not sooner. In a few cases, composers have even been able to give up their day jobs, or have even had to hire help to run their publishing activities. The disadvantages are costs in terms of time and energy and, perhaps, the loss of that caché of being carried by a famous name.

_____

* IMAGEMMUSIC was itself formed in February 2008 when a number of music publishing assets of the Universal Music Group (UMG) were purchased by the Dutch fund ABP, the world's third largest pension fund, and CP Masters BV, an "independent" music publisher.

(A) at a minimum, the publisher offers these three services:

(1) Promotion of the composers' work.

(2) Production and editing, at the publisher's own expense (and not charged against future royalties) of adequate scores, parts, and other performance materials for perusal, sale or rental.

(3) Management of the timely and convenient distribution, rental, and or sale of those materials, including internet distribution of materials in the form of electronic documents.

and

(B) the composer:

(1) doesn't have the time, patience, or desire to do any of the above.

(2) is willing to give up half their performance and mechanical royalties in return for the services.

(3) is willing to trust a publisher to provide the above services over a sustained period of time and in a fashion appropriate to the composer's own interests.

Traditional publishing does continue to carry a certain caché -- it is indeed cool to be able to claim the same publisher as Brahms or Stravinsky, and many a young academic composer facing a tenure decision will be told that they need to get one of their works printed by such a house. But that status has little or nothing to do with the actual tasks of getting music played and heard nowadays, and the current interests of traditional publishers have moved significantly beyond traditional practice.

Take, for example, the case of Boosey & Hawkes, one of the best old firms. In a press release dated Friday, we learn that B&H has been sold by its current owner, HgCapital, to IMAGEMMUSIC,* the music publishing fund of All Pensions Group (APG) and CP Masters BV. This is real success for HgCapital, which paid 75mGBP for B&H in 2003 and now sells it for 126mGBP. Moreover, we learn that, in the past four years, B&H has been significantly restructured, "executing a transformation of the business from a traditional classical music publisher into a 21st century music rights group", and that it has "outsourced a number of non-core activities such as printing and distribution and developed a series of new revenue streams. In particular it has developed a strong presence in the market for music in advertising and film, where revenues are currently growing at approximately 30% per annum." While it is likely that some composers will benefit from this restructuring, it is far from clear that this will be the case for the majority of classical composers, whose interests will necessarily be seen as even more minor within the context of an ever-larger concern.

The alternative is of course, self-publication, as a solo effort (the Stockhausen Verlag or Tom Johnson's Editions 75 are good examples) or in some cooperative arrangement with like-minded musicians (Frogpeak Music, Thürmchen Verlag, Material Press are some examples). The advantages are control over the services provided, retention of royalties by the composer, and direct communication between performers and composers with regard to materials and performances. Electronic publication of scores is a perfect fit both for self-publication and for a musical world in which prospective players want materials now, if not sooner. In a few cases, composers have even been able to give up their day jobs, or have even had to hire help to run their publishing activities. The disadvantages are costs in terms of time and energy and, perhaps, the loss of that caché of being carried by a famous name.

_____

* IMAGEMMUSIC was itself formed in February 2008 when a number of music publishing assets of the Universal Music Group (UMG) were purchased by the Dutch fund ABP, the world's third largest pension fund, and CP Masters BV, an "independent" music publisher.

Friday, April 11, 2008

Remaindered

I just about tossed it in today, almost held up my white flag and gave up the good fight for modernism: I found, in a small corner of English language books, at a discount bookseller here in Frankfurt, right behind the Kleinmarkthalle, two neat stacks containing copies of Gertrude Stein's The Making of Americans and A Novel of Thank You, discounted down to 4.95 Euros. Somehow, it made matters worse that the immediately neighboring stacks, also down to 4.95, were of translated works by Andre Breton. A good chunk of literary modernism thus sat there, till recently almost impossible to get a hold of but now, remaindered.

The stories of what happens to the modern when it is no longer market-fresh-new as a commodity (as opposed to the perpetual novelty of the intrinsic work) is often a curious tale. Near my house in Frankfurt-Praunheim are several settlements of Ernst May Houses from the 1920's, among the most important Bauhaus projects, designed to create mixed-class neighborhoods with affordable multiple and single-family housing. The original designs of the houses, with the pioneering built-in kitchens (designed by the remarkable Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky) and a specially-designed series of Bauhaus furniture, was rapidly modified by the individual owners, with a decided preference for Biedermeier over Bauhaus furnishings and, rather soon, the uniform external decorating schemes for each row of houses gave way to the individual owners painting their houses each as they liked and the cramped quarters were soon expanded by extensions to the buildings front, back, and on top. Now the settlement is as much a museum of 20th-century DYI store fashions for covered entryways, doors, and mailboxes as for the uniform Bauhaus style. As fascinated as I've always been with the modern hardware store and its contents, I'm not altogether certain that the fate of renovation is much different from a fate of remaindering.

As long as we've pondered the possibility that music might have a history, we have searched through the remainder boxes and fussed with renovations. From Monteverdi to Mendelssohn to Busoni, this history has had noble moments, and the gift of notation -- which forces one to use the imagination -- has played no small role. But, in our present age of mechanically and electronically-assisted memory, I'm not altogether certain that we have developed a routine best practice for managing and renewing our musical memories.

The stories of what happens to the modern when it is no longer market-fresh-new as a commodity (as opposed to the perpetual novelty of the intrinsic work) is often a curious tale. Near my house in Frankfurt-Praunheim are several settlements of Ernst May Houses from the 1920's, among the most important Bauhaus projects, designed to create mixed-class neighborhoods with affordable multiple and single-family housing. The original designs of the houses, with the pioneering built-in kitchens (designed by the remarkable Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky) and a specially-designed series of Bauhaus furniture, was rapidly modified by the individual owners, with a decided preference for Biedermeier over Bauhaus furnishings and, rather soon, the uniform external decorating schemes for each row of houses gave way to the individual owners painting their houses each as they liked and the cramped quarters were soon expanded by extensions to the buildings front, back, and on top. Now the settlement is as much a museum of 20th-century DYI store fashions for covered entryways, doors, and mailboxes as for the uniform Bauhaus style. As fascinated as I've always been with the modern hardware store and its contents, I'm not altogether certain that the fate of renovation is much different from a fate of remaindering.

As long as we've pondered the possibility that music might have a history, we have searched through the remainder boxes and fussed with renovations. From Monteverdi to Mendelssohn to Busoni, this history has had noble moments, and the gift of notation -- which forces one to use the imagination -- has played no small role. But, in our present age of mechanically and electronically-assisted memory, I'm not altogether certain that we have developed a routine best practice for managing and renewing our musical memories.

Thursday, April 10, 2008

Music is News That Stays New

When a virus kills its host, then the virus has a problem of its own. (Robert Ashley described the virus as having "shot itself in the foot"). When producers of goods or information, in the downward spiral to control costs in order to compete, reduce the quality of their product or the level of information in their media, they are driven to a point of no return at which their product simply has no more value. Competition is then very much beside the point.

The news today is that the LA Weekly has let Alan Rich go. Rich is, by some distance, the senior active music critic in the US (how senior?, you ask: he heard the premiere of the Bartok Concerto for Orchestra!) and a man of strong and lively words with a lifelong openness to the experimental tradition, going back to his his days as music director at Berkeley's Pacifica station KPFA in the 1950's and throughout a peripatetic career on both coasts. Rich's critical voice is as often convincing as it is contentious, but it always carried the tone of someone who took music more seriously than himself. We are fortunate that's he's vowed to carry on with a web site of his own.

Broken record that this blog may be, let me once again repeat my plea for the importance of new music maintaining a public, online presence. If dead tree media are letting their critics go, each individual story is a sad one (well, not always so sad... there are a couple of critics I'd really like to... never mind) but the larger picture is that through their elimination of actual content, dead tree media are going, slower or faster, the way of the dodo, and the work of establishing an online public presence for our music and the world about that music is more urgent than ever, whatever portfolio -- performer, composer, musicologist, amateur, audient, and yes, critic, too -- we bring to the table. If our music is lively and worthwhile, and I believe it is, then we're obliged to share our sense of that liveliness and value. We have to be more active, more exciting. We have to go long and deep, reaching youth and lay audiences as well as the professional and intellectual, going into both fabulous detail that would have been impossible in traditional media (check out any of Joseph Drew's (Jodru) Stockhausen retrospective at the ANA Blog or Charles Shere's survey of the Milhaud Quartets at The Eastside View) as well as instantly responding (brief, brilliant) to the news of the musical day.

Friends, musicians, critics: do you need any more incentive to get back to work?

The news today is that the LA Weekly has let Alan Rich go. Rich is, by some distance, the senior active music critic in the US (how senior?, you ask: he heard the premiere of the Bartok Concerto for Orchestra!) and a man of strong and lively words with a lifelong openness to the experimental tradition, going back to his his days as music director at Berkeley's Pacifica station KPFA in the 1950's and throughout a peripatetic career on both coasts. Rich's critical voice is as often convincing as it is contentious, but it always carried the tone of someone who took music more seriously than himself. We are fortunate that's he's vowed to carry on with a web site of his own.

Broken record that this blog may be, let me once again repeat my plea for the importance of new music maintaining a public, online presence. If dead tree media are letting their critics go, each individual story is a sad one (well, not always so sad... there are a couple of critics I'd really like to... never mind) but the larger picture is that through their elimination of actual content, dead tree media are going, slower or faster, the way of the dodo, and the work of establishing an online public presence for our music and the world about that music is more urgent than ever, whatever portfolio -- performer, composer, musicologist, amateur, audient, and yes, critic, too -- we bring to the table. If our music is lively and worthwhile, and I believe it is, then we're obliged to share our sense of that liveliness and value. We have to be more active, more exciting. We have to go long and deep, reaching youth and lay audiences as well as the professional and intellectual, going into both fabulous detail that would have been impossible in traditional media (check out any of Joseph Drew's (Jodru) Stockhausen retrospective at the ANA Blog or Charles Shere's survey of the Milhaud Quartets at The Eastside View) as well as instantly responding (brief, brilliant) to the news of the musical day.

Friends, musicians, critics: do you need any more incentive to get back to work?

Sometimes Opening the Inbox is a Good Thing Indeed

Yesterday's email had two good pieces of news: two totally unexpected commissions presenting very different challenges. The first is for an excellent chamber ensemble, flute, clarinet, guitar and percussion, with musicians I trust to do almost anything and do it well. It includes at least one orchestration challenge (for me, the guitar) but I do have a blessedly long time to write the piece. The other is for a large recorder orchestra, perhaps forty players, with instruments ranging from sopranino down to sub-contrabass. Yep, I had to sleep on that one before accepting it, but it does have some interesting potentials and problems (i.e. not making it sound like organ registration or calliopes or, well, a recorder orchestra) and moreover offers a chance to connect to musicians outside of the narrow new music world.

In Pynchon's Against the Day, the phrase "access and agency" jumped out at me; he uses it to describe the opportunities and adventures available to a group of young visitors to the Chicago Fair of 1893 with its admixture of the real and the imaginary. When I'm about to compose a piece, I know that I'm actually ready when I have assembled my own little fairground, with enough exhibits of interest and uncertainty to afford a similar access and agency. So two commissions like these, offering said access and agency, and not without a bit of musical risk, are a very welcome thing, indeed.

In Pynchon's Against the Day, the phrase "access and agency" jumped out at me; he uses it to describe the opportunities and adventures available to a group of young visitors to the Chicago Fair of 1893 with its admixture of the real and the imaginary. When I'm about to compose a piece, I know that I'm actually ready when I have assembled my own little fairground, with enough exhibits of interest and uncertainty to afford a similar access and agency. So two commissions like these, offering said access and agency, and not without a bit of musical risk, are a very welcome thing, indeed.

Wednesday, April 09, 2008

On System and State

I recently got into a bit of a fix trying to explain my piece Decoherence (n) for n orchestras of n players. I fear that my explanation may have led some to conclude, reasonably, that the title was a misprint for Incoherence.

A day or two later, while listening to some great pieces by Gordon Mumma, it occurred to me that in most of Mumma's works various sorts of symmetries play an important role -- in time (palindromes) or in pitch or in the physical space of either the performing space or of electronic circuitry -- but at any given moment the symmetry may actually be represented by its absence, in that a local asymmetry may be a place holder for or within a global symmetry, even if that global symmetry is never actually expressed in the music, pregnantly remaining only a potential. And that situation, the representation of a simple, perfect form by its absence (Feldman's phrase "crippled symmetry" is spot on; I've written here before about the musical uses of pseudo-repetition) seems to me to be a fair description of the greater part of a great deal of music, my Decoherence (n) included.

In Decoherence (n), I tried out, impressionistically, superficially and shamelessly stealing a term from physics with complete disregard for its precise meaning in that discipline, an alternative metaphor for the ensemble process musicians associate with the term counterpoint. Instead of the traditional metaphor of "this against that", I wanted to think instead in terms of lines or surfaces that cohere, sharing aspects of identity when not playing in unison, and then have the capacity to separate in identity, to decohere, and sometimes even have the potential to recohere, to return to identity with one or more of the other ensemble members. Such a program is at least implied by the traditional rules for counterpoint, in that one pays attention to various degrees of similitude between voices and then, according to these degrees, restricts repetitions, to insure that voices are sufficiently different. Thus direct repetitions of perfect consonances are avoided as they lead to melodies that are inadequately differentiated while limited numbers of inperfect consonances in succession are permitted. In my piece, I had the idea that one might then hear the piece as exhibiting various degrees of distance between that of an ideal state, an ensemble unison, and a total lack of cohesion among all of the ensemble's lines, with recoherence serving as an important structural control, bringing things back into recognizable order in the complete ensemble as well as among various sub-groupings with the square number configuration of the ensembles is designed to aid in this. (To be fair to my little piece, Decoherence (3) never strays particularly far into decoherence; it's actually a cheerful little serenade and wasn't altogether inappropriate for a April 1st afternoon.)