A displaced Californian composer writes about music made for the long while & the world around that music. ~ The avant-garde is flexibility of mind. — John Cage ~ ...composition is only a very small thing, taken as a part of music as a whole, and it really shouldn't be separated from music making in general. — Douglas Leedy ~ My God, what has sound got to do with music! — Charles Ives

Thursday, May 31, 2007

More Stokowski on Seating

Via the ever-reliable Pliable of On an Overgrown Path, here is Leopold Stokowski himself talking about orchestral seating, a topic that's registered here before.

Wednesday, May 30, 2007

Variations

It's not news that I often return for ideas to Lou Harrison's Music Primer, as it is full of them, expressed clearly, succinctly, and suggestively. For example, on the topic of variation, one finds this item:

_____

*I don't have a copy handy, but I believe that Marion Bauer's Twentieth Century Music (1933) had a similar list with an attribution to Weiss; Weiss -- Schoenberg's first American student and, for a time, John Cage's teacher -- is a figure about whose activities, as teacher or as composer, we know too little.

FROM THE SCHOOL OF SCHOENBERG: Adolph Weiss' Nine Ways of Varying a Musical Motive: ~ 1) changing the intervals or notes & holding the rhythms, 2) changing the rhythm & using the same tones or intervals, 3) simultaneous combination of both these methods, 4) inversion, 5) elongation, 6) contraction, 7) elision (of one or more notes), 8) interpolation (of one or more notes), 9) the crab form (motus cancrizans, repeating the motive backwards).Both for myself, and with students, I like to start with Weiss' list and invent or discover some other methods of variation. For example, there is the Duchamp method, in which the individual notes (both pitches or durations) are lifted from a measure, phrase, section etc. and then put back in again in the score by chance operations. Then there is the Clarence Barlow style of elision (related to Cage's erasures) in which the rests are substituted for notes (in his Çoğluotobüsişletmesi, Barlow automated the selection of "shoveouts" and "shoveinagains" in order to thin out or thicken a texture). I like another method of working with sequences or rows of pitches, which retains the Schoenbergian idea of waiting to begin again until all of the other items in the sequence or row have been stated, but does so not by a formal operation on the whole set but rather so that, in a 12-tone sequence for example, a note will repeat every 12 tones on average, but only as an average, sometimes repeating every 10 or 11 or 13 or 14 tones, creating small and familiar neighborhoods of pitches, but without every having an exact repetition. (To be honest, I'm most fond of this when used in diatonic or near-diatonic sequences). There are also plenty of possibilities in using contours (i.e. melodic shape, without a metric) as the basic of variations (this was an area pioneered by the composer David Feldman, and later a hot subject in music theory).

_____

*I don't have a copy handy, but I believe that Marion Bauer's Twentieth Century Music (1933) had a similar list with an attribution to Weiss; Weiss -- Schoenberg's first American student and, for a time, John Cage's teacher -- is a figure about whose activities, as teacher or as composer, we know too little.

Tuesday, May 29, 2007

Virtuosity

Here is the first of some sixteen videos at You Tube of Ki Anom Suroto, probably the best-known of contemporary dhalangs in the Javanese Wayang Kulit (shadow puppet theatre). The dhalang is narrator, actor, puppet master, gamelan conductor, lead vocalist, percussionist, and master of ceremonies both spiritual and otherwise, and in the nine-or-so hours of a wayang performance, the universe -- at least that part of the universe that casts shadows on the screen and makes noises sweet or rough -- is under his or her total control, and he or she does not move from his or her position between the screen and the gamelan.

This set of videos include a series of eleven from the Gara-gara scene and five from the Limbukan. The Limbukan, initially a passing scene of little importance involving an emaciated old servant woman and her enormous daughter, has emerged as the principle scene for humor in the wayang, much of it an opportunity to talk very directly about sex. The Gara-gara (pronounced goro-goro) usually begins around midnight, and was initially a moment of contemplation away from the action of the story, during which the hero, for example Ardjuna in the Mahabharata-based plays, takes refuge and is given comfort and counsel by the group of clown-servants, led by Semar, an enormously fat, old, slow, and flatulent figure who is actually an earthly incarnation of the god of love, Sang Hyang Ismoyo. The Gara-gara (the name indicates a time of great strife, chaos, uncertainty) had been a mostly humorous interlude, but has become, in recent years, the central opportunity for musical display by the dhalang, the gamelan, and the corps of female singers, the pesindhen. Ki Anom Soroto has innovated by including a large number of musical items representing repertoire well beyond the courtly traditions of Central Java, and in the case of this video, provides a musical tour of Java, including traditional works from across the island and representations of more popular genres, among them Kerongcong (with some portugese roots), Jaipongan (an urban music originating in the 70s, often with a highly erotic content), and Dangdut (a genre with cosmopolitan borrowing -- Arabic and Malay music, Indian film music, and recently, house and hiphop). Anom Suroto's virtuosity is well on display in this performance, as he leads his soloists and ensemble smoothly from one musical genre to another, and manages to do so within the framework of the Gara-gara and the tonal universe of the slendro-pelog gamelan.

This set of videos include a series of eleven from the Gara-gara scene and five from the Limbukan. The Limbukan, initially a passing scene of little importance involving an emaciated old servant woman and her enormous daughter, has emerged as the principle scene for humor in the wayang, much of it an opportunity to talk very directly about sex. The Gara-gara (pronounced goro-goro) usually begins around midnight, and was initially a moment of contemplation away from the action of the story, during which the hero, for example Ardjuna in the Mahabharata-based plays, takes refuge and is given comfort and counsel by the group of clown-servants, led by Semar, an enormously fat, old, slow, and flatulent figure who is actually an earthly incarnation of the god of love, Sang Hyang Ismoyo. The Gara-gara (the name indicates a time of great strife, chaos, uncertainty) had been a mostly humorous interlude, but has become, in recent years, the central opportunity for musical display by the dhalang, the gamelan, and the corps of female singers, the pesindhen. Ki Anom Soroto has innovated by including a large number of musical items representing repertoire well beyond the courtly traditions of Central Java, and in the case of this video, provides a musical tour of Java, including traditional works from across the island and representations of more popular genres, among them Kerongcong (with some portugese roots), Jaipongan (an urban music originating in the 70s, often with a highly erotic content), and Dangdut (a genre with cosmopolitan borrowing -- Arabic and Malay music, Indian film music, and recently, house and hiphop). Anom Suroto's virtuosity is well on display in this performance, as he leads his soloists and ensemble smoothly from one musical genre to another, and manages to do so within the framework of the Gara-gara and the tonal universe of the slendro-pelog gamelan.

Music: here. Everything else: over there

... just realized that if you asked me about books or films (and probably food or dance or motorcars or visual artworks as well), I could probably rattle off a list of five to ten titles for any best of/worst of category you might come up with. But when it comes to music, putting any of it into lists is a stretch of imagination and will: I don't want to lump the music I value together, let alone rank it. I suppose that's also why I get nervous around folks for whom talk about music mostly turns into references to items in their totally awesome record collections (and which is probably why I can't read much pop and jazz criticism, either): getting close to a piece of music is forgetting the music it resembles or differs from so as to engage the music on its own terms, to change the act of listening into an act essentially indistinct from composition.*

_____

* once again, my debt to Weschler's Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert Irwin is self-evident.

_____

* once again, my debt to Weschler's Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert Irwin is self-evident.

A comic muse

A challenge is now going around to name the best score for a comic film. I suppose a lot depends upon how you define "comic" (I may be alone in defining Eraserhead or O Lucky Man as comic, but I do and their respective scores, by David Lynch and Alan Price, are both fine), and the function of music in a comedy is somewhat different from that in a drama. For example, musical kitsch is almost always a liability in a drama, but in a comic film score it may well be unavoidable and a asset. Here are some favorites:

Bernard Hermann: The Trouble With Harry

Andre Previn: One, Two, Three

Laurie Johnson, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Alex North, Prizzi's Honor

Steven Hufsteter: Repo Man

Toshirô Mayuzumi, Ohayô

John Morris: Young Frankenstein

Charles Chaplin: City Lights

(If I had to choose a favorite, the Morris and Hermann scores are very close, but Mayazumi's wins for its perfect fit to Ozu's sunniest film).

Bernard Hermann: The Trouble With Harry

Andre Previn: One, Two, Three

Laurie Johnson, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Alex North, Prizzi's Honor

Steven Hufsteter: Repo Man

Toshirô Mayuzumi, Ohayô

John Morris: Young Frankenstein

Charles Chaplin: City Lights

(If I had to choose a favorite, the Morris and Hermann scores are very close, but Mayazumi's wins for its perfect fit to Ozu's sunniest film).

Monday, May 28, 2007

Currency of dreams

Functional music (Gebrauchsmusik) is useful, practical, comfortable, amiable, but also replaceable, forgettable, disposable, a currency of everyday life, accompanying motion, labor, ritual, commerce.

In Gilbert Rouget's Music and Trance, it's shown through examples cutting across time and geography that although music may often be a component of trance induction, no specific musical material is associated with this instrumentality; in other words, the music is just a placeholder in the process of induction, and some other, perhaps any other, music could have been substituted.

And that's the problem with functional music -- it is usable, but also disposable and replaceable. If you wanna dance, there's always going to be something else to dance to, and if you want to eat, you'll eat no matter what's on the radio, and if you want to do something more interesting, well, Louis Soleil had Lully, the King of Karagasem had the Gamelan Semar Pegulingan, my father's generation had Jackie Gleason's Velvet Brass and we had Barry White. And while I will use as much functional music as anyone else, enjoying ear candy as if my blood sugar count were zero, I have made the choice that I'm not going to waste any of my limited time and energy for music making on anything other than renewable music, the music that nourishes mind, body, spirit, and keeps at it -- to both comfort and disturb -- for the long haul. That's it: renewable music: currency of our dreams.

(With thanks to David Ocker for disagreeing with me).

In Gilbert Rouget's Music and Trance, it's shown through examples cutting across time and geography that although music may often be a component of trance induction, no specific musical material is associated with this instrumentality; in other words, the music is just a placeholder in the process of induction, and some other, perhaps any other, music could have been substituted.

And that's the problem with functional music -- it is usable, but also disposable and replaceable. If you wanna dance, there's always going to be something else to dance to, and if you want to eat, you'll eat no matter what's on the radio, and if you want to do something more interesting, well, Louis Soleil had Lully, the King of Karagasem had the Gamelan Semar Pegulingan, my father's generation had Jackie Gleason's Velvet Brass and we had Barry White. And while I will use as much functional music as anyone else, enjoying ear candy as if my blood sugar count were zero, I have made the choice that I'm not going to waste any of my limited time and energy for music making on anything other than renewable music, the music that nourishes mind, body, spirit, and keeps at it -- to both comfort and disturb -- for the long haul. That's it: renewable music: currency of our dreams.

(With thanks to David Ocker for disagreeing with me).

Sunday, May 27, 2007

Beyond Zero

In the late 20th century, the impulse to re-imagine music from its foundations was a defining one. Whether making music as or through some formal system (serialism, algorithmic composition), or through a reconsideration of compositional habits (Cage), or through playful concreteness akin to a Wittgensteinian language game (extra point: in how many ways can one connect Reich to Cardew), or in a deeper consideration of the physical matter of music and its psychoacoustical apprehension, there is a least common denominator, and that is the the search for a null point, the place where a music might begin.*

My musical youth was marked by an obsession with this search, whether trying ever-new variations on systems for pushing notes here and there and about, building instruments, experimenting with extended vocal techniques, too many all-nighters in an electronic music studio, obsessively recording environmental sounds, or spending hours in an anechoic chamber or a sensory deprivation tank. In those heady days, the notion that a new music might also represent an alternative form of consciousness didn't raise an eyebrow. Wild times, too: one day, everything seemed possible, and the next, nothing. And always the risk of confusing a self-centered and personal search with a musical result worth sharing. (Some colleagues actually got sucked out of music, per se, and ended up in some profitable and therapeutic corner of the human potential movement or whatever it's now called.)

These days, I have to admit to a certain amount of envy for my younger colleagues who are able to look back easily, without anxiety, at music which came out of these progressive impulses and absorb it at face value, as music, unburdened by ontological questions. And even more, they seem to have some exemption from the need to build each new piece up from nothing, an exemption with which I am not yet blessed.

_____

* The OULIPO lucked onto that wonderful word, "potential".

My musical youth was marked by an obsession with this search, whether trying ever-new variations on systems for pushing notes here and there and about, building instruments, experimenting with extended vocal techniques, too many all-nighters in an electronic music studio, obsessively recording environmental sounds, or spending hours in an anechoic chamber or a sensory deprivation tank. In those heady days, the notion that a new music might also represent an alternative form of consciousness didn't raise an eyebrow. Wild times, too: one day, everything seemed possible, and the next, nothing. And always the risk of confusing a self-centered and personal search with a musical result worth sharing. (Some colleagues actually got sucked out of music, per se, and ended up in some profitable and therapeutic corner of the human potential movement or whatever it's now called.)

These days, I have to admit to a certain amount of envy for my younger colleagues who are able to look back easily, without anxiety, at music which came out of these progressive impulses and absorb it at face value, as music, unburdened by ontological questions. And even more, they seem to have some exemption from the need to build each new piece up from nothing, an exemption with which I am not yet blessed.

_____

* The OULIPO lucked onto that wonderful word, "potential".

Friday, May 25, 2007

Polite. No way.

When I started this blog, I had intended to write about politics ("musical politics, political music, and just plain politics") . As it happens, there's been very little in the way of writing about -- as Terry Riley once put it -- "the big politics in the sky", and that's for three reasons: (1) my observations or opinions are probably unoriginal or unsurprising; (2) as an ex-pat, finding the right tone is difficult; (3) new and classical music is a relatively weak scene on the blogoplan, with a low level of activity and low readership. Because of this, my first commitment as a musician/blogger has been to make a public case for the artistic and intellectual liveliness of my discipline.

I have, however, written about musical politics and although most of the resonance has been in agreement, there have been complaints about "soiling the nest" (a phrase used in more than one email). The message has been that I shouldn't criticize competition fees or raise suspicion of corrupt jury structures* or make fun of the American Music Center simply because it is more important that these institutions exist and create public presences for new music. In other words, I should just buckle down and accept that althought they're not perfect, they're all we've got. While I agree that it is good that these institutions do exist, and if we don't like 'em, then nothing is stopping us from creating alternatives, I believe that we also have to look at the present low profile and slow pace of public activity in the new music scene and consider the real possibility that these institutions have contributed, whether through corruption or the natural and inevitable lethargy of institutions, to that invisibility and stasis.

Avoiding talk about these topics is, in the long run, bad for us, and worse for our musics. If we are to take music seriously, we have to take seriously the ways in which music is handled in public spaces. AFAIC, music is simply too valuable to be handled either as just another slow moving commodity in a micro economy or as a volleyball in an imagined uptown-downtown struggle or as a token in a process of handing out gigs, jobs, and brownie points. Music is more than all that: more differentiated, more valuable, more subtle, and ultimately, more sweet.

_____

* Let me be clear: I do not believe that any individual jurors in the competitions I have mentioned are corrupt, however, processes through which jurors continue to be chosen from a narrow or targeted aesthetic and institutional pool and the organizers are not up front about these processes are corrupt.

I have, however, written about musical politics and although most of the resonance has been in agreement, there have been complaints about "soiling the nest" (a phrase used in more than one email). The message has been that I shouldn't criticize competition fees or raise suspicion of corrupt jury structures* or make fun of the American Music Center simply because it is more important that these institutions exist and create public presences for new music. In other words, I should just buckle down and accept that althought they're not perfect, they're all we've got. While I agree that it is good that these institutions do exist, and if we don't like 'em, then nothing is stopping us from creating alternatives, I believe that we also have to look at the present low profile and slow pace of public activity in the new music scene and consider the real possibility that these institutions have contributed, whether through corruption or the natural and inevitable lethargy of institutions, to that invisibility and stasis.

Avoiding talk about these topics is, in the long run, bad for us, and worse for our musics. If we are to take music seriously, we have to take seriously the ways in which music is handled in public spaces. AFAIC, music is simply too valuable to be handled either as just another slow moving commodity in a micro economy or as a volleyball in an imagined uptown-downtown struggle or as a token in a process of handing out gigs, jobs, and brownie points. Music is more than all that: more differentiated, more valuable, more subtle, and ultimately, more sweet.

_____

* Let me be clear: I do not believe that any individual jurors in the competitions I have mentioned are corrupt, however, processes through which jurors continue to be chosen from a narrow or targeted aesthetic and institutional pool and the organizers are not up front about these processes are corrupt.

Thursday, May 24, 2007

Stacking the Deck

More talk about prizes: The annual BMI awards for student composers have been announced. I can't comment on the selected works as all are unfamiliar to me, but will note that all of the selected works are for conventional ensembles and also note that the academic affiliations of the winners include Indiana U. (Clint Needham, Bryan Christian, Matthew Peterson), Curtis (Sebastian Chang), USC (Eric Gunivan, who is also a IU alum), RAM (Aaron Holloway-Nahum, a Northwestern alum), SUNY Buffalo (Otto Muller), NEC (Nathan Shields) and Peabody (Roger Zare, also a USC alum).

The composition of the jury, however, should be noted:

Chairman of the competition: Milton Babbitt

Jury members: Richard Danielpour, David Dzubay, Christopher Rouse, Gunther Schuller, and Ellen Taaffe Zwilich.

Preliminary judges: Chester Biscardi, David Leisner, and Bernadette Speach.

This is an East Coast establishment jury with real east coast establishment academic affiliations: Princeton, Julliard, Manhattan School, Curtis Institute, Indiana University, New England Conservatory, Sarah Lawrence; Ellen Taaffe Zwilich teaches at FSU, but could hardly be described as representing a non-establishment voice here; the only member of either jury with even a peripheral connection to the experimental music tradition is Bernadette Speach, who studied with Morton Feldman.

Again, I do not know any of the selected works, but given the jury composition and the affiliations of the winners listed above, I think it's safe to say that a young composer with an experimental approach to music, or a composer of electronic music (let's not even talk about circuit benders or hardware hackers or installation composers!), or a composer with a world music orientation would have had a very difficult time with this jury.

To be fair to young composers, especially for the many of them for whom the entry fee can be a hardship, competitions like this should announce the jury membership in advance so that a potential contestant can better judge the chances that his or her work would be taken seriously by the jurors.

The composition of the jury, however, should be noted:

Chairman of the competition: Milton Babbitt

Jury members: Richard Danielpour, David Dzubay, Christopher Rouse, Gunther Schuller, and Ellen Taaffe Zwilich.

Preliminary judges: Chester Biscardi, David Leisner, and Bernadette Speach.

This is an East Coast establishment jury with real east coast establishment academic affiliations: Princeton, Julliard, Manhattan School, Curtis Institute, Indiana University, New England Conservatory, Sarah Lawrence; Ellen Taaffe Zwilich teaches at FSU, but could hardly be described as representing a non-establishment voice here; the only member of either jury with even a peripheral connection to the experimental music tradition is Bernadette Speach, who studied with Morton Feldman.

Again, I do not know any of the selected works, but given the jury composition and the affiliations of the winners listed above, I think it's safe to say that a young composer with an experimental approach to music, or a composer of electronic music (let's not even talk about circuit benders or hardware hackers or installation composers!), or a composer with a world music orientation would have had a very difficult time with this jury.

To be fair to young composers, especially for the many of them for whom the entry fee can be a hardship, competitions like this should announce the jury membership in advance so that a potential contestant can better judge the chances that his or her work would be taken seriously by the jurors.

Wednesday, May 23, 2007

Studying Composition

I've received a good number of emails from younger colleagues asking for recommendations for teachers or schools for composition.

The advice, if I have any, is mostly quite individual rather than general, and there are many factors -- location, price, admissions -- that can eliminate or make possible one solution or another. But the most critical piece of advice I can offer is to study only with a composer whose music you like, who enjoys teaching (i.e. is not just holding down a day job), and with whom you believe that you can have a reasonable chance of getting along.

When it comes to studying composition, it's a buyer's market, and there's no reason anyone should be studying with a teacher who actively dislikes you or your music or vice versa. By all means, interview your prospective teacher, and ask flat out: "What can you teach me?", "How can you help me get my music out into the world?", and -- even more bluntly -- "What financial support do you have on offer?", "If I study with you, can it help me with a career?", "When's your next sabbatical?", "Does the faculty here get along?", and "Do you play to stay here for the next x years?"

The choice of teachers and institutions can have long-range ramifications, so find out what happens to former students. For better or (mostly) for worse, there are real networks out there for distributing performances, commissions, fellowships, prizes, and awards, and find out how well and into which networks your teacher or school is connected. If you want to go an academic route, then the reputation of the institution may be even more valuable that that of the individual teachers in that institution (i.e. in the academic marketplace, a degree from Harvard is worth more on its own than study with any of the composition professors at Harvard, whoever they may be), and there are some places that can get you better placed in niche markets (films, choral or band music, for example) than others. In my case, I looked especially for composers who were successful outside of academia.

I believe that learning to function in an institution of some sort (like a University) is a good skill to acquire sometime in your life, but for many composers, private study may be more useful than study in an institutional context. And also, consider the possibility, that, if you want to compose, many of the musical skills can be self-taught, and using your university years to get a broader or a more practical education may be more useful in the long run than starting off with a narrow focus on musical studies. By a broader education, I mean using the time to become a more interesting person, and by practical, I mean something that you can use to earn a living. Personally, I'll never regret learning Greek or taking anthropology courses, and studies in both have helped my composing, and I do regret not having more maths, which could have been useful to composing.

What a good composition teacher teaches, in the long run is posture (as Charles Olson put it), which is something different from attitude, which most young composers have anyway, and a good composition teacher offers you an alternative set of ears, another perspective on your work, so choose well.

Finally, pay attention to news about the movement of composers into, out of, and among institutions. It is very interesting, for example, to know that Clarence Barlow is now head of composition at UC Santa Barbara, or that the music department at London's Brunel University has recently made a major set of hires, with eight composers on staff (Professorships to Christopher Fox and Richard Barrett) and a solid commitment to new music, or, for a real alternative, how about the Sound department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, led by Nicolas Collins?

The advice, if I have any, is mostly quite individual rather than general, and there are many factors -- location, price, admissions -- that can eliminate or make possible one solution or another. But the most critical piece of advice I can offer is to study only with a composer whose music you like, who enjoys teaching (i.e. is not just holding down a day job), and with whom you believe that you can have a reasonable chance of getting along.

When it comes to studying composition, it's a buyer's market, and there's no reason anyone should be studying with a teacher who actively dislikes you or your music or vice versa. By all means, interview your prospective teacher, and ask flat out: "What can you teach me?", "How can you help me get my music out into the world?", and -- even more bluntly -- "What financial support do you have on offer?", "If I study with you, can it help me with a career?", "When's your next sabbatical?", "Does the faculty here get along?", and "Do you play to stay here for the next x years?"

The choice of teachers and institutions can have long-range ramifications, so find out what happens to former students. For better or (mostly) for worse, there are real networks out there for distributing performances, commissions, fellowships, prizes, and awards, and find out how well and into which networks your teacher or school is connected. If you want to go an academic route, then the reputation of the institution may be even more valuable that that of the individual teachers in that institution (i.e. in the academic marketplace, a degree from Harvard is worth more on its own than study with any of the composition professors at Harvard, whoever they may be), and there are some places that can get you better placed in niche markets (films, choral or band music, for example) than others. In my case, I looked especially for composers who were successful outside of academia.

I believe that learning to function in an institution of some sort (like a University) is a good skill to acquire sometime in your life, but for many composers, private study may be more useful than study in an institutional context. And also, consider the possibility, that, if you want to compose, many of the musical skills can be self-taught, and using your university years to get a broader or a more practical education may be more useful in the long run than starting off with a narrow focus on musical studies. By a broader education, I mean using the time to become a more interesting person, and by practical, I mean something that you can use to earn a living. Personally, I'll never regret learning Greek or taking anthropology courses, and studies in both have helped my composing, and I do regret not having more maths, which could have been useful to composing.

What a good composition teacher teaches, in the long run is posture (as Charles Olson put it), which is something different from attitude, which most young composers have anyway, and a good composition teacher offers you an alternative set of ears, another perspective on your work, so choose well.

Finally, pay attention to news about the movement of composers into, out of, and among institutions. It is very interesting, for example, to know that Clarence Barlow is now head of composition at UC Santa Barbara, or that the music department at London's Brunel University has recently made a major set of hires, with eight composers on staff (Professorships to Christopher Fox and Richard Barrett) and a solid commitment to new music, or, for a real alternative, how about the Sound department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, led by Nicolas Collins?

Hard-learned Practical Advice

If you ever get a transatlantic call in the middle of the night asking you to ghost-orchestrate part of a score for a big Hollywood summer blockbuster space opera, and to do so fast, as in by tomorrow afternoon, accept. But insist on cash payment upon delivery. Remember, when you're doing work for hire, you're just like a repo man, working in a world where contracts are vaprous, and unless you insist on the simultaneous exchange of keys for cash, your fee may be vapor as well.

The Genesis Suite

I've long been fascinated by The Genesis Suite (1945), a project of the composer and conductor Nathaniel Shilkret, and the closest that Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schönberg would ever come to collaborating.

Shilkret's idea was to commission seven composers -- Schönberg, Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Alexandre Tansman, Ernst Toch, and Shilkret himself -- to write pieces for narrator, orchestra and choir based on episodes in the first 11 chapters of the Book of Genesis. Of the seven movements, only Schönberg's Prelude and Stravinsky's Babel survived in print and as repertoire pieces, if fairly rare ones. The scores to Milhaud's Cain and Abel and Castelnuovo-Tedesco's The Flood could be located in manuscripts. The full scores of the remaining pieces, Shilkret's Creation, Tansman's Adam and Eve, and Toch's The Covenant (The Rainbow), were apparently destroyed in a fire in Shilkret's house, but a short score format used for securing copyrights could be used for a recent (2000) reconstruction by Patrick Russ.

As a whole, the "Suite" probably ought best be taken as an artifact of a lost era of Hollywood music making, a scene in which Shilkret was a player, and some of the music is definitely over the top as is only possible in Hollywood (it's too bad that no recording of Edward Arnold's original narration survived; Arnold was a commanding and subtle performer, not at all bombastic). But there are still Schönberg's Prelude and Stravinsky's Babel to consider. The Prelude, as the musicologist Carl Dahlhaus noted, is an audacious idea: to write music representing that which comes before creation, Schönberg chose to write a movement containing a twelve-tone fugue, an audacious notion in itself, given the intimacy between the fugal form and tonal forces. Stravinsky's Babel, on the other hand, is a minor work but nevertheless an excellent primer in Stravinsky's orchestration technique, with surprising details in voicing and register.

The Milken Archive has a good page about this project, which details the history of The Genesis Suite and the recovery and reconstruction of the lost movements, which is available on a Naxos recording.

Shilkret's idea was to commission seven composers -- Schönberg, Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Alexandre Tansman, Ernst Toch, and Shilkret himself -- to write pieces for narrator, orchestra and choir based on episodes in the first 11 chapters of the Book of Genesis. Of the seven movements, only Schönberg's Prelude and Stravinsky's Babel survived in print and as repertoire pieces, if fairly rare ones. The scores to Milhaud's Cain and Abel and Castelnuovo-Tedesco's The Flood could be located in manuscripts. The full scores of the remaining pieces, Shilkret's Creation, Tansman's Adam and Eve, and Toch's The Covenant (The Rainbow), were apparently destroyed in a fire in Shilkret's house, but a short score format used for securing copyrights could be used for a recent (2000) reconstruction by Patrick Russ.

As a whole, the "Suite" probably ought best be taken as an artifact of a lost era of Hollywood music making, a scene in which Shilkret was a player, and some of the music is definitely over the top as is only possible in Hollywood (it's too bad that no recording of Edward Arnold's original narration survived; Arnold was a commanding and subtle performer, not at all bombastic). But there are still Schönberg's Prelude and Stravinsky's Babel to consider. The Prelude, as the musicologist Carl Dahlhaus noted, is an audacious idea: to write music representing that which comes before creation, Schönberg chose to write a movement containing a twelve-tone fugue, an audacious notion in itself, given the intimacy between the fugal form and tonal forces. Stravinsky's Babel, on the other hand, is a minor work but nevertheless an excellent primer in Stravinsky's orchestration technique, with surprising details in voicing and register.

The Milken Archive has a good page about this project, which details the history of The Genesis Suite and the recovery and reconstruction of the lost movements, which is available on a Naxos recording.

Minimalism, once more

No, that's not it. -- N.O. Brown

I tried, in a few recent posts, to reclaim the term minimalism, a term that, to my mind has been hijacked by a revisionist view that seeks to define it narrowly as a musical style and limit it to a particular -- closed, historical -- repertoire. I didn't do a very good job, so let me try again:

Minimalism in music is the impulse to articulate or frame a musical work or performance so that the sounds themselves can be clearly perceived as distinct or composite forms and in maximum detail. To achieve this clarity, the number and variety of materials used will usually be limited, and any formal processes used will usually be efficient, evident, and carried out consequently .

This impulse may lead to, if not actively entertain, several, possibly paradoxical, effects:

- materials or processes selected for their simplicity may reveal, through clear compositional articulation and focused listening, unexpected details, even complexity;

- although an honest or realist approach, music so articulated may open up its own musical/acoustical illusion spaces;

- this physical and experiential mode of production and listening may resonate with abstract or conceptual modes of understanding;

- the materials selected may recall or be identified with known musical repertoire.

(image: from the score to Hauke Harder's 320 BPM "Why Beats?" (1991) for flute, piano and glockenspiel).

Monday, May 21, 2007

Goldfinger and Cage

Ben Harper of Boring like a Drill has a great post about John Cage's one-time master teacher in Architecture, Ernő Goldfinger, and solves the mystery of Goldfinger's pop cultural immortalization in a famous spy novel. Now someone has to do a number on Cage's own pop cultural immortalization, in the stage name of an Oscar-winning actor (born Coppola) and, possibly, as a character in a TV legal/soap.

A Composer's Environment

Kraig Grady passes on this story about Roy Harris:

When Roy Harris moved from the beach he was asked "Why?" Harris said "All my music is starting to sound like Debussy."

Later, he moved from Topanga (Canyon) and was asked the same question. Harris replied "Too many damn birds. My music is starting to sound like Messiaen."

*****

I suppose I'll have to leave Frankfurt when my music starts sounding too much like (take your pick) Telemann, Humperdinck, Hindemith, or Mangelsdorff.

When Roy Harris moved from the beach he was asked "Why?" Harris said "All my music is starting to sound like Debussy."

Later, he moved from Topanga (Canyon) and was asked the same question. Harris replied "Too many damn birds. My music is starting to sound like Messiaen."

*****

I suppose I'll have to leave Frankfurt when my music starts sounding too much like (take your pick) Telemann, Humperdinck, Hindemith, or Mangelsdorff.

Virgil's Orpheus

I started a project late last year around Orpheus and Eurydice, perhaps because, having just hit 45, the theme of not looking back had taken on a certain attraction if not urgency. However, without a commission in hand, it has been more open-ended research than finished product and often seemed to be going nowheres faster than somewheres.

However, Patrick Swanson came to my rescue and sent me into Virgil's Georgics, that astonishing poem on farming, work, the universe and everything else (Douglas Leedy put it this way: "I'm in there, and you are, too."). Following Patrick's invitation, I quickly set a small passage from Book 1, in part a response to the bellicosity of the present regime in Washington and perhaps some other small songs will follow.

The Georgics, of course, has its own version of Orpheus and Eurydice in Book IV (yes, the book with the bees):

However, Patrick Swanson came to my rescue and sent me into Virgil's Georgics, that astonishing poem on farming, work, the universe and everything else (Douglas Leedy put it this way: "I'm in there, and you are, too."). Following Patrick's invitation, I quickly set a small passage from Book 1, in part a response to the bellicosity of the present regime in Washington and perhaps some other small songs will follow.

The Georgics, of course, has its own version of Orpheus and Eurydice in Book IV (yes, the book with the bees):

ipse cava solans aegrum testudine amoremThese are lines about singing that ought to be sung; suddenly, the outlines of my older project have taken on a substantial form.

te, dulcis coniunx, te solo in litore secum,

te veniente die, te decedente canebit.

May Sweeps In Music Blogland

Yes, it's time again: Scott Spiegelberg has posted his survey of the top fifty or so classical music blogs, proving once again that if this blog is in the top fifty, classical music blogs are still far from finding their potential audience.

I wish to assure you that Renewable Music has not skewed its editorial content in advance of what we may call "classical music sweeps week", and the following topics have not been mentioned here:

Tinfoil hats, engram-meters, orgone accumulators, alien abductions, neo-conservatism, dowsing, homeopathy, fired US Attorneys, creationism and/or intelligent design and/or flying spaghetti monsters, ancient astronauts, perpetual motion machines, paparazzi photos of troubled heiresses or pop stars (and certainly neither Paris Hilton nor Britney Spears), Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, biodiesel, John Lott's sockpuppet, Jerry Falwell, Joyce Hatto, Bee colony die-outs, or the busking Joshua Bell.

Well, okay, I did mention the bees and Bell, and alluded to Hatto, but those were relevant...

I wish to assure you that Renewable Music has not skewed its editorial content in advance of what we may call "classical music sweeps week", and the following topics have not been mentioned here:

Tinfoil hats, engram-meters, orgone accumulators, alien abductions, neo-conservatism, dowsing, homeopathy, fired US Attorneys, creationism and/or intelligent design and/or flying spaghetti monsters, ancient astronauts, perpetual motion machines, paparazzi photos of troubled heiresses or pop stars (and certainly neither Paris Hilton nor Britney Spears), Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, biodiesel, John Lott's sockpuppet, Jerry Falwell, Joyce Hatto, Bee colony die-outs, or the busking Joshua Bell.

Well, okay, I did mention the bees and Bell, and alluded to Hatto, but those were relevant...

Sunday, May 20, 2007

Meet-a-Composer Roulette

In idle moments -- of which you may correctly suspect I've far too many -- why not get acquainted with an unfamiliar composer?

Here's one way: go to http://netnewmusic.net/ and choose a name at random from the right-hand column. If the name selected is familiar, reload the page, and try again.

Here's another way: go to the birthday page at the American MusicCartel Center's New Music AlmsTinderSnuffBox and choose one of today's birthday children, or enter a favorite or random date and see who turns up.

(Note: the NMB's birthday list is limited to US composers (and even then, at least one day in September is deficient by at least one expatriate Californian.))

Today I got to learn a bit about: Alexandra Gardner and Ludmila Ulehla.

Here's one way: go to http://netnewmusic.net/ and choose a name at random from the right-hand column. If the name selected is familiar, reload the page, and try again.

Here's another way: go to the birthday page at the American Music

(Note: the NMB's birthday list is limited to US composers (and even then, at least one day in September is deficient by at least one expatriate Californian.))

Today I got to learn a bit about: Alexandra Gardner and Ludmila Ulehla.

Saturday, May 19, 2007

Lessons in Counterpoint : Observe the Bagel

Virgil Thomson usefully suggested that one describe a contrapuntal setting in terms of the number of voices, the characteristic intervals between the voices, and whether the voices were were differentiated or undifferentiated in character. Since the basic idea of counterpoint is that two or more melodies are chugging along simultaneously and that those melodies are distinct, a degree of differentiation is basic, and the various sets of rules for counterpoint that emerged from either observation or speculation are designed to insure some degree of distinction, for example through the exclusion of parallel unisons, octaves, and fifths and limits on the number of consecutive parallel thirds or sixths (which are more distinct in melodic character than the "perfect" unisons, octaves, and fifths through their admixtures of major and minor intervals).

But this differentiation can be greater or lesser. Sometimes a composer would like an ensemble in which the individual voices are relatively indistinct and it is less important to perceive the individual lines as distinctive melodies. This can be achieved by using uniform rhythms, a similar and narrow tessitura, compact voice leading (which is not quite the same as a parsimonious voice leading as such a setting may also include voice crossing), etc..

Often, however, a composer chooses instead to increase the differentiation, moving on an axis of differentiation from homophonic to heterophonic, while remaining in the same place in the monophonic/polyphonic axis, as they say in the systematic musicology biz. While this may be done by brute force, increasing the variation from line to line in contour, rhythmic content, etc., it may also be desirable to figure out how to increase differentiation without necessarily decreasing the audibility of the individual lines.

Observe, for a moment, the bagel, or its toroid, sweet, and goyischer sibling-by-topology, the common fried doughnut. These are two, as far as we know, independently developed, examples of finding the same solution to the problem of an optimal form for a differentiated texture in a bread-like good. With a torus* of relatively uniform dimension, the ratio of crust to sponge, or surface to mass, is optimized, allowing a more even distribution of heat during the boiling and baking or frying processes, and -- in cooperation with a cool rising in which yeast and bacteria are encouraged to get to work as well -- maximizing the distinction between smooth and relatively dense, if not hard or crispy, crust and the airy sponge. (The presence of the whole also assists in draining a doughnut of oil or a bagel of water). The success of both baked goods is largely due to this spatial optimization, and from that we can perhaps intuit a bit about making the lines in our contrapuntal ensembles more distinctive.

Space is a common metaphor for the pitch-height continuum among musicians, and if one wants to differentiation voices it is certainly useful to separate them in space (sometimes, in an ensemble, it is useful to have subgroups of voices separated from one another, for example, in a choir, separating male and female voices, or the lower voices from a soaring treble line, or in basso continuo, the bass line from the upper voices). But allow me now to push the spatial metaphor a bit further, and suggest that it is useful to consider that each individual line possesses a number of spatial elements -- and those concern both tessitura (in height, and extent, and whether its pitch space is a sole possession or shared or overlapping with other voices) and, more critically, contour, the melody's crust. We might even describe contour in terms cannily like those used to describe a crust -- is it smooth? is it variegated? does it cover the range of a melody in a compact way or does it wander? In a contrapuntal ensemble, the contrast between and -- frequently -- the audibility of the individual voices can be increased by using alternative tessituras and surfaces.

_____

* The torus, is of course, familar to all students of tuning theory as the toroid projection is ideal for describing a tuning system in which two generating intervals (fifths and major thirds, for example) are so tempered as to form closed cycles of pitches upon a single lattice. I recall once showing a toroid tuning lattice in a dissertation by Scott Mackeig to the theorist Ervin Wilson, who asked the inevitable: "But does it sound like a doughnut?"

But this differentiation can be greater or lesser. Sometimes a composer would like an ensemble in which the individual voices are relatively indistinct and it is less important to perceive the individual lines as distinctive melodies. This can be achieved by using uniform rhythms, a similar and narrow tessitura, compact voice leading (which is not quite the same as a parsimonious voice leading as such a setting may also include voice crossing), etc..

Often, however, a composer chooses instead to increase the differentiation, moving on an axis of differentiation from homophonic to heterophonic, while remaining in the same place in the monophonic/polyphonic axis, as they say in the systematic musicology biz. While this may be done by brute force, increasing the variation from line to line in contour, rhythmic content, etc., it may also be desirable to figure out how to increase differentiation without necessarily decreasing the audibility of the individual lines.

Observe, for a moment, the bagel, or its toroid, sweet, and goyischer sibling-by-topology, the common fried doughnut. These are two, as far as we know, independently developed, examples of finding the same solution to the problem of an optimal form for a differentiated texture in a bread-like good. With a torus* of relatively uniform dimension, the ratio of crust to sponge, or surface to mass, is optimized, allowing a more even distribution of heat during the boiling and baking or frying processes, and -- in cooperation with a cool rising in which yeast and bacteria are encouraged to get to work as well -- maximizing the distinction between smooth and relatively dense, if not hard or crispy, crust and the airy sponge. (The presence of the whole also assists in draining a doughnut of oil or a bagel of water). The success of both baked goods is largely due to this spatial optimization, and from that we can perhaps intuit a bit about making the lines in our contrapuntal ensembles more distinctive.

Space is a common metaphor for the pitch-height continuum among musicians, and if one wants to differentiation voices it is certainly useful to separate them in space (sometimes, in an ensemble, it is useful to have subgroups of voices separated from one another, for example, in a choir, separating male and female voices, or the lower voices from a soaring treble line, or in basso continuo, the bass line from the upper voices). But allow me now to push the spatial metaphor a bit further, and suggest that it is useful to consider that each individual line possesses a number of spatial elements -- and those concern both tessitura (in height, and extent, and whether its pitch space is a sole possession or shared or overlapping with other voices) and, more critically, contour, the melody's crust. We might even describe contour in terms cannily like those used to describe a crust -- is it smooth? is it variegated? does it cover the range of a melody in a compact way or does it wander? In a contrapuntal ensemble, the contrast between and -- frequently -- the audibility of the individual voices can be increased by using alternative tessituras and surfaces.

_____

* The torus, is of course, familar to all students of tuning theory as the toroid projection is ideal for describing a tuning system in which two generating intervals (fifths and major thirds, for example) are so tempered as to form closed cycles of pitches upon a single lattice. I recall once showing a toroid tuning lattice in a dissertation by Scott Mackeig to the theorist Ervin Wilson, who asked the inevitable: "But does it sound like a doughnut?"

Friday, May 18, 2007

from our FAQ

How does a Renewable Music item come to be written?

While there are naturally a number of procedures unique to this enterprise that we've chosen to keep proprietary, I can speak for the rest of the staff here in the Home Office in Praunheim and praise the work done by our R.&.D. team in Pacoima. The R.&.D. team has developed, with the aid of some programming outsourced to the South Asian offices of the Oublogo, an algorithm for determining the (a) frequency, (b) length, (c) principle, subsidiary, and dangling subject matters, (d) degree of sustained relevance to the subject matter(s), as well as determining, through extensive polling of a target audience (Island- and mountain-dwelling over-educated service sector refuseniks

and praise the work done by our R.&.D. team in Pacoima. The R.&.D. team has developed, with the aid of some programming outsourced to the South Asian offices of the Oublogo, an algorithm for determining the (a) frequency, (b) length, (c) principle, subsidiary, and dangling subject matters, (d) degree of sustained relevance to the subject matter(s), as well as determining, through extensive polling of a target audience (Island- and mountain-dwelling over-educated service sector refuseniks with mild-but-reasonable paranoia and over-sensitive moral fibers), the (e) nature of any opinion to be expressed in an item. Of course, in practice, the process is a bit more complicated, as when this week the program determined that the subject would

with mild-but-reasonable paranoia and over-sensitive moral fibers), the (e) nature of any opinion to be expressed in an item. Of course, in practice, the process is a bit more complicated, as when this week the program determined that the subject would be one tangential to the theme of Jimmy Carter, relevant to music, and contain an approximation of Wagnerian assonance, hence the post on Melisma malaise.

be one tangential to the theme of Jimmy Carter, relevant to music, and contain an approximation of Wagnerian assonance, hence the post on Melisma malaise.

That's very interesting, but what do you do when the program is out of order?

The Home Office always keeps a manual data base (blue-and-red-lined white card stock, 3"x5") from which topics can be determined by our thoroughly-tested in-house method (seven perfect shuffles and a Carson City top-to-bottom force). The topics in this data base (e.g. food, making fun of the critic-who-shall-not-be-named or the American MusicCartel Center, food, the evils of contest fees, food, counterpoint, croquet) are continuously being updated and, as always, are thoroughly tested in surveys with a target audience (Slovenes, cable television meteorologists, active Hibernian-rite Masons and bridal photograph colorists). Sometimes, however, the data base is inaccessible, or lost, or just gone walkies with one of the kids, in which case Dr. Wolf simply writes whatever he damn pleases.

While there are naturally a number of procedures unique to this enterprise that we've chosen to keep proprietary, I can speak for the rest of the staff here in the Home Office in Praunheim

That's very interesting, but what do you do when the program is out of order?

The Home Office always keeps a manual data base (blue-and-red-lined white card stock, 3"x5") from which topics can be determined by our thoroughly-tested in-house method (seven perfect shuffles and a Carson City top-to-bottom force). The topics in this data base (e.g. food, making fun of the critic-who-shall-not-be-named or the American Music

Thursday, May 17, 2007

Blogger problems?

Is anyone else having difficulties with Blogger? Lately, it's taken a very long time to load pages, log in, upload pictures, and, worst of all, the comment functions have been slow and buggy.

55 Layers of Dough

One solution to insomnia is an all-night baking project. And making croissants is a solution to insomnia for a fundamentally lazy person (that'd be me): although it takes 12 hours or so of elapsed time, there are only 10 or 15 minutes of actual work involved. Croissants are made of a yeasted dough with layers of butter folded and refolded in to create very thin layers. In the recipe I use (Child & Beck, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume Two, where else?), this ends with 55 layers, achieved through treble folding four times: 3, 7, 19, 55 (after the initial fold, two layers are lost in each additional treble fold because they are folded from the outside, and thus have no butter to separate themselves from their neighbors; this sequence, by the way, has some relevance to the theory of musical temperaments). (Photo: our breakfast table, this morning).

One solution to insomnia is an all-night baking project. And making croissants is a solution to insomnia for a fundamentally lazy person (that'd be me): although it takes 12 hours or so of elapsed time, there are only 10 or 15 minutes of actual work involved. Croissants are made of a yeasted dough with layers of butter folded and refolded in to create very thin layers. In the recipe I use (Child & Beck, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume Two, where else?), this ends with 55 layers, achieved through treble folding four times: 3, 7, 19, 55 (after the initial fold, two layers are lost in each additional treble fold because they are folded from the outside, and thus have no butter to separate themselves from their neighbors; this sequence, by the way, has some relevance to the theory of musical temperaments). (Photo: our breakfast table, this morning).

The pleasures of the open score

David Toub has a nice post on the advantages of composing an open score. He was fortunate to have a piece played by the Diverse Instrument Ensemble (aka D.I.E.) at CSU Fullerton. D.I.E. is an innovation of Prof. Lloyd Rodgers (a fine composer and a teacher), and something that every self-respecting music department should have -- an on-going ensemble without a fixed instrumentation as an opportunity to get ears and hands into a wide range of music -- early music, new music, all the stuff in-between, and perhaps even a glance at non-western traditions, with the emphasis on experimenting as a group with ways to make the music come off the page rather than replicating a received performance tradition. In other words, the exact opposite of the usual band, orchestra, and choir.

A while back, I made a suggestion that there should be an "Online Book of Consort Lesson", a page with links to scores with open instrumentation. Let's make this happen.

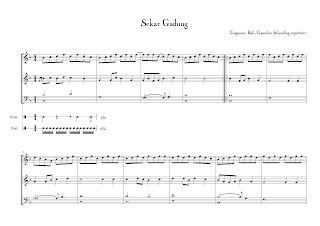

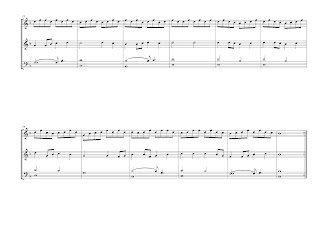

Added: To get things going, here's a transcription from the Salunding (archaic iron gamelan) repertoire of the Bali Aga village of Tenganan. Play the whole thing several times, a bit slower with the upper cengceng (a nest of small cymbals -- try substituting a closed high hat) part, a bit livelier with the lower part:

A while back, I made a suggestion that there should be an "Online Book of Consort Lesson", a page with links to scores with open instrumentation. Let's make this happen.

Added: To get things going, here's a transcription from the Salunding (archaic iron gamelan) repertoire of the Bali Aga village of Tenganan. Play the whole thing several times, a bit slower with the upper cengceng (a nest of small cymbals -- try substituting a closed high hat) part, a bit livelier with the lower part:

Wednesday, May 16, 2007

Melisma malaise

A common complaint among US composers about opera is that operatic writing over-uses melismas. Ornament, in general, is out, and stretching out a syllable over too many notes is way out. The proffered solution is to ban melismas altogether. Funny thing: this complaint is often made in the same thought stream which says that art music for the theatre ought to sound something more like pop music, or at least borrow generously from pop techniques -- microphones, mixing, clear text setting, clear distinction between melody and accompaniment, everpresence of a beat, maybe even a hook, etc.. But, how does that reconcile with the enduring fashion for ornament, yes even the dreaded melisma, in the pop song world? We're in an odd world indeed in which new operas should avoid melisma while singers in the Top 40 or on American Idol are expected to o.d. on them.

A similar prejudice is that against vibrato, but I think that the problem is neither vibrato or melisma in themselve, but rather lack of control over each, leading to their presence as a default setting in both composition and performance practice. The way out, of course, is that we simply have to do better: singers have to learn to use vibrato as an ornament that can be turned on and off, and when on they must be able to control its depth, duration, and speed, and composers have to give more thought to the use (and possible of abuse) of melisma, as one direction on a field of possible relationships between pitches and words.

A similar prejudice is that against vibrato, but I think that the problem is neither vibrato or melisma in themselve, but rather lack of control over each, leading to their presence as a default setting in both composition and performance practice. The way out, of course, is that we simply have to do better: singers have to learn to use vibrato as an ornament that can be turned on and off, and when on they must be able to control its depth, duration, and speed, and composers have to give more thought to the use (and possible of abuse) of melisma, as one direction on a field of possible relationships between pitches and words.

Tuesday, May 15, 2007

Landmarks (24)

Edgard Varèse: HYPERPRISM (1923) for nine wind instruments and percussion. Music was never more "modern" than it was in the "ultra-modern" 1920's* and the controversial issues around that modernism -- dissonance, noise, radical breaks in continuity, extremes of materials, intensity of expression -- have never really been settled in subsequent music history, but rather continue to percolate in-between bouts of more restrained music-making. Condensation is one of the prominent tropes in early modernism, but Varèse's condensation in HYPERPRISM is unrelated to that of the Viennese Schönberg and Webern, for whom condensation was a means of intensifying an expressive tradition. For Varèse condensation is rather a means of concentrating -- viewing through a prism, if you will -- a musical idiom that is assertively a- or even anti-traditional. (While Stravinsky's music is associated with the idea of "tonality by assertion", here we have an "atonicization by assertion"). HYPERPRISM is a miniature in terms of its elapsed duration, but not in terms of the resources required or its ambitions. The percussion section fills an unprecedented portion of the ensemble, the winds play at extremes of register and dynamics, and within the span of just four minutes the piece moves through a dozen distinct changes of tempo and character (it's tempting to speak of movements here). But for all the extremes, there are numerous subtleties, for example the opening c#', shared, rearticulated, recolored by the tenor trombone and horns, and in the percussion, the changes of scoring patterns and composite ensemble rhythms.

_____

* As long as we're at it, if you consider Pulchinella, music was never more postmodern than in the 1920's!

_____

* As long as we're at it, if you consider Pulchinella, music was never more postmodern than in the 1920's!

Happily nonharmonic

Reading an item about a composer very different from myself, I was once again struck by a notion that, despite all the old and familiar and -- sometimes -- unreconcilable aesthetic and stylistic differences, there is in fact one area of new compositional activity in which there is widespread engagement, a common project even, albeit one that is content to find a diversity of compositional solutions rather than embracing any single hegemonic path.

I'm thinking here of the project of working within a tonal environment that includes a wide spectrum of possible pitch configurations, with, on the one end of the spectrum, configurations similar to harmonic spectra and on the other, configurations approaching or including noise. Along this spectrum, one can locate all the familar animals in the tonal music zoo, with structures paralleling harmonic and subharmonic series, and all of the more exotic ones as well, in which pitch space is divided in an equidistant or a more unruly way, or those which are the residua of conflicts between voice leading and harmony, and even incorporate some real harmonic xenofauna, culled from further reaches of the harmonic spectra or other divisions of pitch space. And, through rescaling, one can include musical phenomena that were previously considered too subtle for compositional elaboration if not inaudible, for example those of interference beats and combination tones.

Perhaps I'm being overly optimistic and generous to describe a project with such a broad scope, but it has real roots in historical theory and compositional practice -- consider the treatment of contrapuntal dissonance and, later, nonharmonic tones, topics that were hot from the start and reached an apogee in the conflicting approaches of Schenker's voice leading and Schönberg's expanded catalog of chords. More contemporary approaches are manifold and resonant: Cowell's attempts to locate clusters in an overtone series, Seeger's dissonant harmony, the Stockhausen of ...how time passes... , the phonetics research, and Sternklang, the largely-francophone timbre/harmony or spectralist project (with its ultimate roots in Fourier and Rameau), Robert Erickson's Sound Structure in Music, James Tenney's John Cage and the Theory of Harmony, and late Cage's own "anarchic harmony", and, most recently, William Sethares's idea-rich book Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale.

But a composer needn't approach the notion of an expanded continuum of pitch relationships with a heavy theoretical apparatus; this can be taken in intuitively. A personal landmark for me was encountering La Monte Young's release of a disk with a vocal and electronic performance within a well-behaved harmonic series flipped by a B-side of a continuously bowed gong, a sound that was both distant from and continuous with, the harmonic material of the A-side. When Andriessen and Schönberger, in their delightful book on Stravinsky, The Apollonian Clockwork, observe that Stravinsky often used harmonies with bell-like structures, they are locating Stravinsky's tonal practice on precisely this sort of continuum. While it's certainly possible to elaborate more, I don't think that a compositional (or speculative) theory needs much more scaffolding than that to simply get to the business of composing.

I'm thinking here of the project of working within a tonal environment that includes a wide spectrum of possible pitch configurations, with, on the one end of the spectrum, configurations similar to harmonic spectra and on the other, configurations approaching or including noise. Along this spectrum, one can locate all the familar animals in the tonal music zoo, with structures paralleling harmonic and subharmonic series, and all of the more exotic ones as well, in which pitch space is divided in an equidistant or a more unruly way, or those which are the residua of conflicts between voice leading and harmony, and even incorporate some real harmonic xenofauna, culled from further reaches of the harmonic spectra or other divisions of pitch space. And, through rescaling, one can include musical phenomena that were previously considered too subtle for compositional elaboration if not inaudible, for example those of interference beats and combination tones.

Perhaps I'm being overly optimistic and generous to describe a project with such a broad scope, but it has real roots in historical theory and compositional practice -- consider the treatment of contrapuntal dissonance and, later, nonharmonic tones, topics that were hot from the start and reached an apogee in the conflicting approaches of Schenker's voice leading and Schönberg's expanded catalog of chords. More contemporary approaches are manifold and resonant: Cowell's attempts to locate clusters in an overtone series, Seeger's dissonant harmony, the Stockhausen of ...how time passes... , the phonetics research, and Sternklang, the largely-francophone timbre/harmony or spectralist project (with its ultimate roots in Fourier and Rameau), Robert Erickson's Sound Structure in Music, James Tenney's John Cage and the Theory of Harmony, and late Cage's own "anarchic harmony", and, most recently, William Sethares's idea-rich book Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale.

But a composer needn't approach the notion of an expanded continuum of pitch relationships with a heavy theoretical apparatus; this can be taken in intuitively. A personal landmark for me was encountering La Monte Young's release of a disk with a vocal and electronic performance within a well-behaved harmonic series flipped by a B-side of a continuously bowed gong, a sound that was both distant from and continuous with, the harmonic material of the A-side. When Andriessen and Schönberger, in their delightful book on Stravinsky, The Apollonian Clockwork, observe that Stravinsky often used harmonies with bell-like structures, they are locating Stravinsky's tonal practice on precisely this sort of continuum. While it's certainly possible to elaborate more, I don't think that a compositional (or speculative) theory needs much more scaffolding than that to simply get to the business of composing.

Monday, May 14, 2007

Celebrity

I was always shy about talking to John Cage -- he was, after all, someone of my grandparents' generation, and I seldom imagined having anything to say that would be worth bothering him. When N. O. Brown invited me to join Cage and himself for a walk in the woods above Santa Cruz, that's all I did: walk, keeping enough distance so as to stay out of their chat. My first actual conversation with Cage took place during the Cabrillo Festival in the summer of 1981. I picked up my ringing telephone and immediately recognized that voice with its almost-absent fundamental asking ''Gordon?''. Somehow I put one and one together -- someone with the phone numbers of both Gordon and myself had mixed them up and given mine to Cage -- and very quickly answered: ''Mr. Cage, this is actually a wrong number, but I just happen to have Gordon Mumma's number''. He answered: ''then it isn't a wrong number at all.'' At some point, I did ask Cage about possible composition teachers; he suggested Lou Harrison, Gordon Mumma, and Alvin Lucier. (I also asked him about studying with La Monte Young and he asked whether I was religious.) Needless to say, Cage's advice was sound, and I took it.

Sunday, May 13, 2007

Festive Klang

This was the weekend of Hessischer Rundfunk's first "Klangbiennale." The program included concerts with forces from solo to chamber ensembles to full orchestra and a baker's dozen of sound installations scattered around the Funkhaus. The motto -- not quite a theme -- of the festival was "Kraft-Werke", and Elliott Sharp, represented by solo, chamber, and orchestral performances was an appropriate headliner. The featured guest composers included Maria de Alvear, Robyn Schulkowsky, Jens Joneleit, Matthia Kaul, and Dániel Péter Biró. Also included were works by Lucier, Hába, Nono, Tenney, Carter, Adams, and others.

I'm not a critic, so I won't review the program in any depth, but I do have a few observations:

A first observation, unsurprising for a festival devoted to Klänge, was that the music chosen tended to emphasize timbre and texture over other elements, and the European and American responses to such an emphasis could not have stood in greater contrast -- with the European tending toward more intuitive approaches and rather more unruly sounds while the Americans favored formal clarity and simpler harmonic spectra. Hearing Lucier's Navigations for Strings next to Hába's 16th Quartet and then Nono's A Pierre. Dell'azzurro silenzio inquietum next to Tenney's Critical Band made this contrast explicit. (Nota bene -- the Tenney performance suffered because the players played the score in good faith, as written; unfortunately, Tenney had made a substantial change in how he wanted the piece played with regard to a continuous pulse and never corrected the score to indicate this; anyone who would like to play it should consult with players experienced with rehearsals under Tenney's direction. Nota-not-so-bene -- with late Nono, the state of the scores and the electronics required to realize many of them is distressing and that raises some fundamental questions about the nature of the works; but this deserves another post, another time).

A second observation is that sound installations are seriously boring these days. There should be a voluntary moratorium on installations in which recordings are simply played back through any array of loudspeakers, there should be more installations which do not involve loudspeakers in the first place (heck, there should be more installation which do not involve electricity), and it would be nice if, from time to time, an installation involved an object or contraption or an array of such objects or contraptions that was or were lovingly crafted and attractive to look at, instead of being thrown or cobbled together from industrial and consumer detritus.

A third observation is that Maria de Alvear is working in the same thematic territory that Varese was in his late, unfinished, works (Nocturnal, Nuit, Dans la Nuit, etc.), and that being explicit like de Alvear or Varese about sex in music is difficult territory, and any effort is going to be provisional (one-piece stands, if you will). Classical concert audiences are prudish by nature and her piece, Sexo, never found a way to effectively challenge that prudishness other than through assertion and duration (the sexual politics of the piece were not clear), but perhaps that was the point. There is nothing remotely intimate about a full orchestra in a hall like the HR's broadcast hall, gymnasium-sized and covered on all sides by basketball court-quality parquet, and de Alvear's non-stop narration struck me as too syntactic, too full of whole sentences, too full of, well, sense, to ever invite the audience to loosen up, but again, that might have been the point. On the other hand, there was striking orchestration, so strikingly unlike anyone else's orchestration that the border between naive and knowing was clearly in play, making the whole a compelling 70 minutes.

A fourth observation is that Dániel Péter Biró is a young composer to whom attention should be paid. I have rarely experienced music that was both so obviously musical and so unapproachably strange, and Biró's Simanim, for nine players and electronics was just that.

And a final observation is that although HR's programming has always been more friendly to the US than any other European broadcaster, this was ultimately a very European festival. It's hard to imagine any institution in the US sponsoring a festival with a program including as much "difficult music" as this one. It is equally hard to imagine that during a American concert groups of concert-goers would gather together in the breaks and cheerfully argue about Kantian aesthetics while munching down Currywurst.

I'm not a critic, so I won't review the program in any depth, but I do have a few observations:

A first observation, unsurprising for a festival devoted to Klänge, was that the music chosen tended to emphasize timbre and texture over other elements, and the European and American responses to such an emphasis could not have stood in greater contrast -- with the European tending toward more intuitive approaches and rather more unruly sounds while the Americans favored formal clarity and simpler harmonic spectra. Hearing Lucier's Navigations for Strings next to Hába's 16th Quartet and then Nono's A Pierre. Dell'azzurro silenzio inquietum next to Tenney's Critical Band made this contrast explicit. (Nota bene -- the Tenney performance suffered because the players played the score in good faith, as written; unfortunately, Tenney had made a substantial change in how he wanted the piece played with regard to a continuous pulse and never corrected the score to indicate this; anyone who would like to play it should consult with players experienced with rehearsals under Tenney's direction. Nota-not-so-bene -- with late Nono, the state of the scores and the electronics required to realize many of them is distressing and that raises some fundamental questions about the nature of the works; but this deserves another post, another time).

A second observation is that sound installations are seriously boring these days. There should be a voluntary moratorium on installations in which recordings are simply played back through any array of loudspeakers, there should be more installations which do not involve loudspeakers in the first place (heck, there should be more installation which do not involve electricity), and it would be nice if, from time to time, an installation involved an object or contraption or an array of such objects or contraptions that was or were lovingly crafted and attractive to look at, instead of being thrown or cobbled together from industrial and consumer detritus.