A displaced Californian composer writes about music made for the long while & the world around that music. ~ The avant-garde is flexibility of mind. — John Cage ~ ...composition is only a very small thing, taken as a part of music as a whole, and it really shouldn't be separated from music making in general. — Douglas Leedy ~ My God, what has sound got to do with music! — Charles Ives

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Ups & Downs

There's some talk going about worsts these days, whether worst (p)residents or worst(-written) reviews (start here). I'd like to add the review which most effectively convinced me that the performance in question was, indeed, a worst-of-its-kind. It was not a concert review, but a course review of a course taught by a professor who happened to be a music professor. The effective line in the review went: "(this course) compared unfavorably to having battery acid poured on your genitalia."

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Temporary Notes (11)

Tempo, tempo! Let me admit that I've been casual about tempo markings; in part this is because I want to have the latitude necessary to make a piece work under different performance conditions — different room acoustics and physical placements of players, different instruments (individual instruments often "speak" and resonate very differently), and, of course, different players — as well as to allow for the precise tempo and variations in tempo to remain, to some extent, an element within the interpretive domain. And I'll further admit that my tempo markings have often been either completely intuitive (just keep adjusting that metronome until it sounds right) or completely pragmatic (i.e. setting a common pulse to a nice round number so that complicated rhythms are easier for players to rehearse), and sometimes they have been ambiguous or downright vague, particularly when I use words rather than a numerical indication. I could probably get along reasonable well with this casualness, but in a performing environment with so many competing traditions and influences, it's definitely helpful to be clear about things whenever flexibility, ambiguity, or vagueness is not intended. (Also, as someone who does, for better or worse, think a lot about music, it's somewhat careless not to think through something as basic as tempo).

There is some very useful material online about tempo. For more contemporary concerns, I recommend this webpage by composer John Greschak. For an exhaustive treatment of a historical repertoire, I recommend this webpage on the time signature and tempo markings in Mozart.

Greschak's page forced me to go back and read Mälzel's "Notice on the Metronome". Beyond the mechanical interest of the device, the main interest for me is in his scaling of tempi, and, as a composer, this is a very useful place to begin thinking about tempo, regardless of the precise (or imprecise) relationship of his ideas and gadget to historical practice. Mälzel basically envisioned four basic tempos, each measured by a different basic unit or pulse: for Adagio, the eighth note, Andante, the quarter, Allegro, the half, and Presto, the whole. Within a basic tempo, the pulse may vary a bit up and down, with Mälzel describing 80 per minute as "moderate", meaning a typical or middling rate for the tempo in question. (The number 80 seems to be taken from Quantz who identified it with the human heartbeat. "Moderate" is a really problematic word: it can mean middling, or can indicate a slowing down (or retreat from an extreme position), in the sense of moderation; a good word to avoid in scores, Ithinks). From this moderate value, one can interpolate the assais and moltos that vary down or up from the middling, and, also, interpolate tempi like Allegretto or Larghetto which fall about midway between the basic tempi. What I draw most usefully from Mälzel is making the basic counting unit clear in the score, i.e. eighth = 80. The words have their archaic and exotic charm, and if you are making a stylistic reference to historical repertoire, then go ahead and leave the words in, but not without the numerical markings. The interpretation of these words has changed and will change over time, but my physicist friends assure me that we're unlikely to experience a change in values for a minute anytime soon. In my case, I'll try to drop using words for the tempo, but this will not stop me from using words to indicate other expressive suggestions.

Now about the scaling of tempi. Metronomes are still made set to Mälzel's original scale, which approximates, in whole numbers, a 16-step scale between 40 and 80: 40, 42, 44, 46, 48, 50, 52, 54, 56, 58, 60, 63, 66, 69, 72, 76, 80. Digital devices now widely available offer more precision than this, but these tempi are still likely to have been internalized by practicing musicians. (Somewhat akin to perfect pitch, many musicians are able to memorize tempi, and some even execute the most complicated emsemble rhythms by drawing on their reserves of such internalized tempi. What a piece of work!) As Greschek points out, Cowell and Stockhausen each proposed tempo scales based on 12 divisions of a tempo "octave", in Cowell's case, just intonation-based "scales" dividing the tempi spaces 60-120 and 48-96, and in Stockhausen's case, an approximation of an equal tempered division between 60 and 120. Stockhausen used these tempo markings throughout his work rather consistently. Being personally unattached to the number 12, I can probably get along just fine with the conventional 16 values, but if I had to take 12, I would go with 60, 64, 68, 72, 76, 80, 84, 90, 96, 100, 106, 112, which uses only three speeds not found on the tradional metronome (64, 68, 90), one of which (90) is easy to accurately perform in proportion to the basic value of 60.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Edge of an Era

Which is just to get 'round to the observation that other, similar events, arrived in a similar, slinking way*: the Great Depression didn't hit in the moment of the crash of '29, it came in fits and starts, and people were well into very bad times before the severity and potential duration of the event was even somewhat clear (prosperity, you know, just being around the corner). Likewise in music history, folks didn't wake up one morning in 1750 and decide, all together & spontaneously, that they were fed up being baroque and that it was time to get down and get classical. How about the "rock'n'roll" era? Mine was one of those lower-middle-class households which turned on the B&W Zenith to watch the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. But the interest was novelty (the noise, the haircuts, the suits w/o collars), not the music. After the "event", my father put on an LP of the Cal Tjader Latin Jazz Concert or Jackie Gleason's Velvet Brass to hear some "real music". Nope, even with significantly large and influential works & deeds & events, these were — and are — processes with long, slow burns. The polyphony of styles and methods and materials and ideas that characterizes contemporary composition and music distribution and reception basically eliminates the possibility of a sudden of overwhelming change. Sure, there are single works that have tremendous impact, and single composers who seem larger-than-life, but look closely, and in every case, I'm sure that you'll find that the impact is gradually, not sudden. I think it took a quarter-century for In C to register, for example, a work of decisive and international impact on two generations of composers, but the wake of In C was initially very slow, of low amplitude and more than a little ambiguous. Was it about tonality? Texture? Improvisation? Loops and phases? Nowadays, we hear In C through the perspective of its wake, and from the perspective of "minimalism" (a term unused at the time of its composition), and the immediate ancestors of In C are all but forgotten. I know several people who heard the first performance of In C. All of them agree that something fundamentally changed with that experience, but what changed immediately was the individual sense of the nature, extent, and limits of their own music-making, not the change in the nature, extent, and limits of music-making in general that we recognize today. In music, this change comes without an edge, individual listener by individual listener, not in grand and universal events dividing the moment decisively from everything that came before it.

_____

* I think I have to add this: as a child, maybe five or six years old, I had a recurring nightmare, from which I would wake in tears and cold sweats of terror. It involved a slinky, or something like a slinky, a wire coil that would keep moving forward, step-by-step, increasing in size, volume, and ever-so-slowly in tempo, until the movement, which had begun as that of a modest toy had become menacingly loud, gigantic, and insistent.

Monday, November 24, 2008

That shock

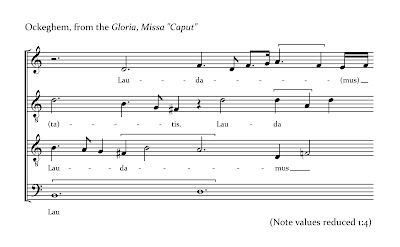

Ockeghem is astonishing. First, for the constant invention of his tunes. Ockeghem makes all the familiar moves, locally, but assembles the moves into long and unpredictable continuities (someone, certainly, is at this moment writing a dissertation on the Fractal Complexity of Ockeghem's Melodic Lines). Second, for shocking moments — like that above — is which the diversity of lines in the ensemble converge — here going absolutely in your face with a cross-relation f#-f'-natural, enjoying a direct move from one extreme to the other of his tonal resources* — into something approaching, when not actually, epiphanic.

_____

*Come to think of it, a lot of modern music gets by with the shock value of shifts no greater than O.'s here, from a b minor triad to a d minor triad. Heck, that's just about enough harmonic material for a very satisfying evening at the Mabou Mines. (Yes, Virginia, O. didn't think of it in those terms, but have you any doubt that he heard it?).

Sunday, November 23, 2008

Who'd have thought it?

If Sapir & Whorf had been Inuit or Yup'ik or Aleut, how much time would have been wasted talking about all those English words for snow (i.a. Artificial snow (aka Grits), Blizzard, Blowing snow, Chopped powder, Columns, Corn, Cornice, Crud, Crust, Dendrites, Depth hoar, Finger drift, Firn, Flurry, Freezing rain, Graupel (aka Snow pellets), Ground blizzard, Hail, Hailstorm, Heavy crud, Ice, Lake effect snow, Needles, Packed powder, Packing snow, Penitentes, Pillow drift, Powder, Rain & snow mixed (aka Sleet, Ice pellets), Rimed snow, Slush, Snirt, Snow squall, Snow storm, Snowdrift, Snowflake, Soft hail, Surface hoar, Watermelon snow, Wind slab)?

It's snowing here. Back in my electronic music days, I was obsessed for a time with trying to get sounds out of snowflakes, not the sounds they make when they hit surfaces in aggregate form, but the individual sounds of each vibrating crystal. Many years later, this became a serious interest of scientists and mathematicians, and the sounds of ringing snowflakes are now available, amplified and transposed downward into audible range. I find these sounds beautiful but somewhat disappointing because they are essentially static, musically-speaking. They are divorced of the narrative thread into which snowflakes enter our lives. Just think of that first line of Frank O'Hara's Wind (To Morton Feldman), the text Feldman used in his Three Voices: "Who'd have thought that snow falls..."

Saturday, November 22, 2008

Libretto Fashions

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Inversion

It strikes me that the greatest difficulty posed by this structure is that The Head and The Tail are, ultimately, delivering something very different to the market, leading to some of the substantial conflicts over intellectual property raging at the moment. @ The Head, a small number of products are being produced and delivered in mass, and income is a direct result of the sale of these products, which for music, are recordings. But @ The Tail, recordings do not very often have primarily a direct income-producing function: recordings are essentially calling cards, advertisements, and momentos for live performances. This creates a fundamental conflict of interests between artists @ The Head & @ The Tail when it comes to issues like licensing for internet broadcasts or file sharing. It is difficult for me to recognize a possible resolution to this conflict within the structure of contemporary performances rights organizations, in which larger producers @ The Head, tend to have voting control and at the same time, one has to recognize that facts on the ground have long been established by consumers who simply copy & share with all of the encouragement of the corporate structures that created the devices with which they copy & share.

Performance rights organizations are already intensely engaged in this problem of products and market environments, the structures of which are, for the two ends of the market, essentially inversions. It is probably not very difficult to create two parallel systems for compensation to cover this, but it will be a very delicate operation to determine what music belongs @ The Head and what @ The Tail, as well as to design mechanisms for the smooth movement of work from one end to the other, as market interest for work becomes either more general or more specialized over time.*

(As a composer of concert music, & one whose work is located very much and mostly contentedly in The Tail, I cannot realistically anticipate ever making significant income from sales of recordings. Live performance licenses, however, do provide a real source of income to me. GEMA, my own performing rights organization, has gone one step in the right direction by allowing members to place recordings of their own works on their own websites without a licensing fee. I still have no intention of investing much energy in recording, but having a few more calling cards or free samples is probably a good idea.)

_____

* This is a critical issue in performing rights organizations as well, as voting membership is awarded after producing a certain income level for a certain period of time and is then, generally, irrevocable, thus filling the voting membership with authors who are no longer productive or whose interests in the most current market conditions are somewhat limited.

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

What just intonation can do for you

When I first started working with just intonation in the mid-seventies, it was cool but definitely not yet the minor fashion it has become; my work in the area was even actively discouraged by many musicians, composition teachers among them. Now that tuning to intervals of small and smallish whole number ratios has become substantially more acceptable — and alternative/microtonal tunings in general, including historical tunings and tunings outside the western traditions — the rationale for going to the extra effort required to get intonation right is often obscured, sometimes even by extravagant claims by proponents. Adorno famously "defended Bach from his devotees"; let me try a similar defense for just intonation.

Often, just intonation is promoted as more "natural" or better representative of the natural tendencies of real performing music. This argument doesn't work for a number of reasons. First, because we have little or no data to confirm that just intonation is the prevailing habit or intention. Intonational control is hard, and musicians in all traditions, even the most esteemed, show wildly varying skills in pitch control and replication. There are special instances, in barbershop singing, for example, in which practice clearly includes targeting harmonies to just intonation, but this done intuitively rather than formally, and the melodic practice required to yield those harmonies is complex, and species of temperament, informal and intuitive in its own terms. Further, the "natural" intonational tendencies of musicians are far from universal, with the particular instrument and repertoire and practice tradition playing large roles, as well as the unique intonational preferences of individual musicians (the Javanese would call this embat, literally "bouncing", as in the sense in which each person walks with their own lilt). The tendency of western string players towards large major thirds and leading tones is an afffinity with pythagorean intonation, but one which contrasts starkly with the affinity of horn players, for example, to tune to harmonic series segments, but these are only tendencies and actually practices is rather more pragmatic. Instrumentation is also important because not all instruments have simple harmonic spectra, thus, for these instruments, just intonation is not inevitably optimal in terms of reduced spectral beating.

Often, just intonation is promoted in the abstract, by an appeal to reason, indeed to the world of platonic ideals. Your own mileage will necessarily vary on this one, but my own interest is in real, existing music in the world I happen to live in. Nevertheless, I personally find that an abstract approach to just intonation, classifying intervals by the odd or prime factors in their ratios, provides a superb method of sorting through and mapping (typically onto a lattice or manifold) tonal materials and one that, to a large extent, corresponds closely to my experience of those materials in the acoustic reality of music made well.

One argument that does work, and bridges the abstract and real qualities of intervals just intonation is this: Just intonation makes intervals and the tonal relationships among them more explicit. This may well come at the loss of some useful possibilities for tonal ambiguity, particularly those offered by temperaments, but there are alternative forms of ambiguity offered by an extended just intonation and it is a legitimate musical aesthetic to not use such ambiguities.

But, in the end, the most important justification is simply this: with voices and with instruments with simple harmonic spectra, just intonation provides the set of intervals which will maximize sensory consonance. Not taking advantage of this as a composition resource — and, implicitly, the entire range of sensory consonance and dissonance afforded by subtle and not-so-subtle deviations from these intervals — is rejecting one possibility for the qualitiative enrichment of music and, from this point of view, is making music less rather than as much as it might be.

See also this earlier post, What alternative tunings can do for you

Monday, November 17, 2008

Originale, the movie

Here's an interesting document from a moment when the faultlines in the post-war avant-garde were not altogther so clear: Stockhausen's Originale: Doubletakes, a film by Peter Moore, is a distillation of the New York premiere of Stockhausen's theatre piece, Originale, in the context of the 2nd Annual New York Festival of the Avant Garde. The core of Originale, here under the stage direction of Allan Kaprow, is the piece Kontakte, performed by James Tenney (piano) and Max Neuhaus (percussion). In addition, the cast features Charlotte Moorman (cello), Alvin Lucier (conductor), Jackson MacLow and Dick Higgins (as "actors"), Allen Ginsberg (as "poet"), and — of course — Nam June Paik, reprising the role he created at the work's premier, a part identified in the score by Paik's name.

(hat tip: rec.music.classical.contemporary).

Arpeggiated Bleg

Golden Age

I've just finished reading Andrew Barker's The Science of Harmonics in Classical Greece. While there is probably a bit too much detail here for readers without background in tuning theory, classics, or the history of science, I find this to be really exciting stuff. The book is an account of scholars (and musician-scholars) trying to make sense of real musical practice while developing the set of tools we now recognize as "science". This story is extremely useful for those of us who follow more contemporary music theories, not only because some of the ancient harmonics survives as terminology and structure in modern music theory, but also because the lines of research — the range of those lines as well as the conflicts among them — also surves in contemporary practice. Harmonics was, at once, idealistic, looking toward pythagorean and platonic ideals for the proportions among tones, but it was also observant of musical practice and, chiefly through the figure of Aristoxenus, a nascent science of perception.

Imagining ancient Greek music is a formidable task. We have the difficulty of historical distance and the lack of evidence that accompanies that distance. We have the problem of not re-constructing a single, highly localized, musical culture, but actually a series of cultures extending over the better part of a millenium and stretching throughout the ancient world. We have the problem of unclear degrees of continuity with contemporary practice. From a modern and western European viewpoint, we have the added difficulty of reconstructing an ancient mediterranean culture to which we undoubtedly owe some debt, but our glance backward tells us too little about a culture which looked forward in a number of directions, and the glance towards western Europe was among the most distant.*

But for all that difficulty, it's our fortune to live in a virtual golden age of scholarship about ancient Greek music and the culture around it. In addition to Mr Barker, whose collection of translations of the surviving manuscripts of music theory is also invaluable, Martin L. West and Warren D. Anderson have written very useful summary volumes, Pöhlmann and West have made a useful edition of the surviving examples of notated music, and Stefan Hagel has a great site of reconstructed melodies here.

_____

* Lou Harrison once pointed out to me that the famous missing chapter of Boethius' On Music concerned the division of the fourth into two parts (in contrast to the tetrachordal division into three parts). Lou practically shouted: "It's NOT missing. Someone just wanted to erase the connection between Greece and Africa." While Lou's idea of an intentional erasure is pure conjecture, it is true that trichordal lyre tunings are still practiced in Ethiopia, and these tunings are just one step removed from classical Greek tetrachords.

Saturday, November 15, 2008

Material

In the early 90's, the composer Hauke Harder & I started a music publishing project which we called Material Press. We never actually discussed precisely why Material was the right name, but I recall an instantaneous agreement on the matter, which is not untypical of my chats with Hauke. I suppose that the immediate rationale was that we simply wanted to provide performance materials — scores, some recordings, some special equipment — for music (by ourselves, some contemporaries, like Markus Trunk and Ann Warde and some esteemed senior figures, Lucier, Mumma, and, for a time, Young), which we thought was important. But, with all the benefits of hindsight, it's become increasingly clear that Material was exactly the right word, if, increasingly, because of a paradoxical effect: the moment in which musical material is articulated as a central feature is the same moment in which the ephemeral nature of musical material is most clear. (Together now, with that nostalgic refrain: All that is solid melts into air.)

Material Press is not an unusual development in terms of composers controlling their own publishing (Tom Johnson and Stockhausen provided some models), or in terms of doing it cooperatively (the Feedback Studio was one model, and both Frog Peak Music and the Thürmchen Verlag were like-minded contemporary efforts), but we were perhaps unique in a few aspects: our composers kept all of their royalties (that is to say, we're not registered as a publisher with a rights organization), have individual control over pricing, and are free to distribute the materials in any other ways they see fit. There are some things we could do better — the editions could be more beautiful (i.e. more suitable for library purchases), we could promote more, and we could use the web more wisely (i.e. making more scores available for download) — but, on balance, I think we do a good job on a break-even basis in supplying materials so that performances can take place.

In the new year, I'll be resuming a more active role in Material Press (Hauke took over when I moved to Budapest in 2000). Expect topics related to publishing, especially to doing publishing better, to appear here more often.

Friday, November 14, 2008

NMZ starts blogging

Muziekplein

Architecture exempted?

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Cause & Effect

This past week, I had five sessions of radiation therapy, preventive measures for something that could eventually become a major inconvenience, nothing life threatening (it is truly humbling to spend time in a hospital department in which most patients have concerns much more serious than your own). As it seems worthwhile getting rid of this while it is still in an early stage, I've managed to temporally put aside fears of matters atomic. There was an odd disconnect to the procedure, which involved an impressively large machine, a linear accelerator to be precise, but we can call it an x-ray, which made a nasty enough sawtooth-like noise as it shot photons at my left foot, and yet for all the theatre of the treatment there was no immediate effect. Maybe a bit of tingling or warmth, but that was probably more my imagination at work than anything else. You go into something like this with enormous expectations, but postive results are only supposed to show up over a time period of six months or so, so there is a real disconnect. It's something like the circus clown who threatens with an outsized gun and then fires, only to have a bouquet of fake flowers or a little flag with the word "BANG!" written on it pop out instead. And while, in a theatrical context, such anti-climaxes can be effective, startling, and amusing, the routine I'm hoping for is effective and reassuring, with as little surprise as possible.

One of my favorite sound installations (and one that is uniquely effective as a concert piece, as well) is Alvin Lucier's Music for Pure Waves, Bass Drums and Acoustic Pendulums (1980). Like the large hospital equipment I've been admiring, it involves a somewhat preposterous physical apparatus: four bass drums in a row with loudspeakers hidden behind the drums, and four ping-pong balls suspended from the ceiling by fishing line, each ball resting on the head of its own drum. As the oscillator makes a slow sweep, the drum heads respond sympathetically, eventually moving enough to cause the balls to bounce. The balls bounce in response to the individual characteristics of each drumhead, the frequency and amplitude of the sine waves, and the timing of each bounce with regard to the relative positions and velocities of the ball and drum head. One soon starts to perceive patterns of repeated bounces, automatically framing them as little rhythmic units, but these patterns are quite local in both time and physical space, and the combinations of the four drums in concert creates a composite rhythm of a complexity well beyond that of a three-body problem. Best of all, the regular bouncing of a single ball (and sometimes a duo, trio, or quartet) may suddenly stop, dead, when the drum head suddenly curves inward in a — and this is literally and mathematically true, in the sense invented by René Thom — catastrophic change of shape. This is truly funny, like slapstick, and the obsever may well have a somewhat tragic response to the lonely ping pong ball, also like slapstick (at its best). We are obviously in the presence of a phenomenom with causes and effects, but the precise nature of those causes and effects is continuously obscured and nothing beyond that is obvious.

In the composition and experience of a work of music as a continuity, there is considerable tension between two ideals: the first is one in which continuity is maximally smooth, with every cause immediate to an effect and every effect clearly traceable in memory to a cause. This is a largely comforting feature of music, an order setting aside music-making from the disorders of everyday life. But this can also result in a nightmarish monotony. The other ideal is that music can equally well embrace surprises, maximum disjunctions in continuity, causes which are divorced from effects, familiar processes made strange (think of deceptive cadences and false recapitulations), and unrelated materials can be simply juxtaposed without the intervention of connecting or explicating materials (Stravinsky's "assertion"). In practice, all the music that I understand (and, perhaps, you, too) as interesting, no, good, music finds some special, if not unique, balance between these two ideals. Some repertoires may emphasize one ideal rather than the other (music for the theatre — opera and dance —, for example, became more heavily invested in rapid changes in continuity than did concert music, and the most lasting impact of this is probably in film editing, which borrowed much from music-theatrical continuity, well before films carried their own sounds!), perhaps individual composers settle into emphasizing one more than the other over their careers and catalogues.**

_____

* Was anyone else, as a young reader and movie-goer, troubled by Dr. Seuss's change of Bartholomew's surname from Cubbins to Collins?

**My friend, David Feldman, a composer and mathematician, in talking about this blog item, suggested that it would be useful for me to read up on symbolic dynamics.

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

Selection and Chance

The interaction between human selection and chance is here carefully managed, and one has no doubt that the politically savvy churchmen will be lobbying heavily in advance to insure that the three names placed into the envelope are equally acceptable. In general, I have a lot of respect for such decision making processes, in which a community first comes to agreement that a certain number of alternatives are all acceptable rather than offering alternatives that are acceptable to only approximate halves of the whole community and letting the actual decision fall to a rather small portion of the electorate, and that portion frequently composed of the most indicisive, while simultaneously leaving nearly half the community unsatisfied with the choice.

(A similar practice was once the case at Cowell College, the oldest of the residential colleges at my own undergraduate school, UC Santa Cruz: to qualify for office in the college's student government, all candidates were to compose and recite a certain number of lines of rhymed verse, and the winners from this select community of scholar-poets were chosen by a drawing from hat.)

It is fairly well-known that many composers in recent generations have taken to the use of chance operations in their work. For many of us, works of John Cage provided an immediate model. Unfortunately, it is often perceived that the introduction of chance operations into the decision-making procedures of a composer are in some one an abdication of composerly choice. This view is facile and has often unfairly prejudiced listeners against the work, a prejudice which has been amply exhibited against the works of Cage in particular. This is unfortunate, as the application of chance operations by Cage was always in the context of a decision-making process like the first step of the election of the Serbian Orthodox Patriarch, one in which composerly choice, indeed individual composerly taste and imagination, identified a collection or field of acceptable possibilities, from which the final decision would be extracted, and the result of that decision is one which is thus both acceptable and, in detail or particular configuration, combination, or sequence, unforeseen. This is a process which accepts chance but is firmly based upon knowing what one is doing. The hand of God is a nice rhetorical turn, but the hands at work here are entirely human.

Monday, November 10, 2008

Neither here nor there

The first email, from a composer and presenter in the US, went:

It looks elegant, but impossibly difficult to realize. It's embarrassing to admit, but (we) can not afford adequate rehearsal to do your piece justice.

The second email, from a presenter in Germany, went (my translation):

I like your piece, XXX, very much. It's very American in character. But sorry, it's too simple for us. Our flute player only wants to present himself in public with more challenging material.

Contradictory evaluations like these, coming from opposite sides of the pond, are not that unusual. It is not my impression that the players here are necessarily better than those there (or vice versa), but rehearsal possibilities do seem to be highly — and increasingly — constrained in the US compared with much (but certainly not all) of Europe, and there are some trends in aesthetic preferences, through which more complex scores are usually better received here while scores that are more conventionally tonal or relate more immediately to conventional performance practice are generally preferred in the states.

What I do really don't know how to respond to is the label "American in character," but nearly every review I've had here makes a point of this, and usually before actually saying anything about the music. I suppose I find "Californian" less objectionable, as the tradition I identify with is probably better defined by a bit more localization, but it's still somewhat beside the point. On the other hand, in the US, my music sometimes gets labelled "European," and too many times the accident of my living here gets used, as if to qualify my music or my words. If I had a nickel for every message that starts out "living in Frankfurt, you really have a different..." from someone who has no idea what life in Frankfurt is like or what I do here... Almost inevitably, it is connected with some insinuation that "I've had things better" over here, which is not necessarily the case. While some things (like GEMA, the local performance rights organization) have generally been better for new musicians than the US equivalents, almost none of the remaining support structure — radio stations, publishers, concert series — for new music is functioning as well as it did even a generation ago, and Europe simply does not have the supply (however Americans may complain) of teaching jobs that continue to employ a number of composers; even the film scoring work I've ghost written from time to time has all come from the US. Moreover, in Europe, it is generally far more difficult to do things from scratch, whether organizing a concert or publishing a score. (In real political terms: better a tightly competitive market than none at all, sez I.)

In any case, I'm flattered by the bit of unsolicited attention in my little flute piece. And while it may not be getting many more performances, I take some pleasure in the notion that in terms of musical qualities (character, style, difficulty, whatever), it's neither here nor there, but perhaps, very much itself after all.

Division of Labor

Saturday, November 08, 2008

American, Experimental, Robust

The programmed music played really divided into two groups, one of which was our mainstream and not-so-quiet musical school of quietude (thanks again to Silliman's term from Poe), typified by works by Bernstein, Carter, and Crumb, which, for all their differences in materials, technique, or style, were still examples of music which is all about pushing all the right emotive buttons. I don't like being pushed, I don't like being reminded that I have those buttons which might get pushed, and I don't like music which substitutes button pushing for musical invention. There was some Ives and Gershwin on the program as well, fairly standard choices for programs like this, and the honesty of the styles made a strong contrast in particular with the Bernstein, music which just tries too damn hard, and often ends up a dog's breakfast. (With so much going on simultaneously, I missed the parts of the program devoted to European composers who emigrated to the US, including works, especially songs, by Schoenberg, Hindemith, Milhaud, Weill, which surely added an interesting local prospective to the notion of an American repertoire).

The second group was music in the experimental tradition, ranging from the New York School (Cage, Wolff, Feldman) to now-classics in the tributaries of the radical/minimal tradition (In C, part one of Drumming, The People United Will Never Be Defeated) as well as Adam's Phrygian Gates, a work which I heard at one of the very first performances, and now, increasingly sounds more at home with the mainstream, but very much a fine piece of American string writing. (Isn't astonishing, that, for a nation in which wind bands have always been more locally prevalent than orchestras, we do such a good job with strings?) In contrast to the mainstream repertoire, which largely came out of the Musichochschule's traditional performance studios and standing ensembles, using traditional rehearsal techniques, this repertoire was assembled more on an ad hoc basis, using non-standard, often flexible instumentation, and sometimes requiring quite a bit of non-traditional engagement in order to realize a score. For all that, this music is extraordinarily robust, and one realizes now, as In C and Drumming enter middle age, that these works have become standard repertoire, and are programmable in an incredible diversity of means, settings, and circumstances. Moreover, these works remain fresh by virtue of this robustness. The performance of In C, for example, led by the local percussion professor (and long-time Ensemble Modern member) Rainer Römer, was for a subdued and slightly under-tempo ensemble of five mallet percussion, two cellos, and two clarinets. Initially, I wanted to object to the use of register contrasts introduced in this performance, particularly in the extended bass-range marimba, but I was soon convinced that this was a useful way of projecting details in the texture that are frequently lost in large ensemble performances which restrict themselves to the notated register. I am far from certain that this particular performance practice is strictly allowed by the "rules" of the piece, but it did show that the material was still rich for experiment.

As a caveat to the remarks above, two works by Feldman illustrated real limits to the notion of robustness. Chorus and Instruments II simply fell flat; as music which depends upon disappearing into and coming out of silences, the traditional choral performance style is inadequate (as the choir members have to seize pitches out of nowhere, they have to constantly bounce tuning forks against their heads in order to get reference pitches, adding some odd theatre), a typical choral audience is unprepared for it, and the typical concert hall is unsuited for it. (Heinz-Klaus Metzger got it spot on when he remarked that Webern was the last compose to write before the advent of air conditioning). On the other hand, with a piece like Why Patterns?, played well last night by students of the Ensemble Modern Academy, Feldman quite effectively solved the problem of creating musical continuity sufficient to exclude external distractions from a music which is so dynamically reduced and subtle.

Friday, November 07, 2008

Bush Pardon Watch

Now, however, is a time for cooler emotions to prevail, and the next administration is faced with a range of problems on an unprecedented scale. By all accounts, Sen. Obama has uniquely cool temperament, appropriate to these times. I was a bit taken back by the theatre of Obama's speeches in Berlin, at the convention, and in victory in Chicago: just a single figure on a ramp — not really a stage — and not the usual view of a candidate crowded in a field of pols. This image fundamentally clashed with the non-royal "we" of his message, but perhaps it was a useful sign that he is taking on high office without the usual variety of political debts. I hope that Obama has the creativity to match his cool to move to solutions that are more fundamental in nature. The goal is not just to fix the current mess, but to make some long-overdue, perhaps even radical, changes for the better. The financial crisis, energy policy, environmental policy, health care, education, and social security are issues that interconnect and must be solved in parallel motion (if sometimes in a form of lively but dissonant counterpoint), with the extra benefits of such coordinated action likely to pay off in numerous other ways, for example in the war on terror and the critical relationship to the developing world in general.

We still have too many days before Obama takes office and a lot of damage remains to be done by the Bush residency. Look out, especially, for the flood of pardons to come, particular to members or benefactors of the administration. (Heck, I can imagine Bush pardoning his VP a day before his term ends, then promptly resigning so that a Resident Cheney can pardon Bush in return.) Maybe, in an act of vigilance, we should all flood the White House with pardon requests, for whatever little crime we may have once committed: when I was 14, I failed to stop at a stop sign on my bicycle and got a suspended sentence, I have committed too many parallel fifths and octaves to count, and I once pulled that "do not remove" tag off of a hotel mattress. I also stole some soap from the same hotel. Pardon me, Mr. Bush!

Monday, November 03, 2008

Maxfield Documentary

My apologies for having lost the hat tip, but someone recently pointed to a very good 1974 radio documentary on the electronic music of Richard Maxfield made by Charles Amirkhanian, complete with excerpts from a 1960 interview with Maxfield by Will Ogdon. (As a bonus, there is a very strong piece homage to Maxfield by Amirkhanian himself in the program).

The interview presents a lively picture of Maxfield as a proponent and exponent of the then-novel ideas of incorporating chance techniques into composition and indeterminant elements into realisation or performance of compositions. These ideas were, of course, associated first with John Cage, but it is exciting to see how readily they were taken up and wrestled with by other artists, in this case, a composer who had come from Berkeley and Babbitt's Princeton as a card-carrying 12-tone composer with a significant portfolio of instrumental compositions (many or most of which are in the library at UCB), had made his European grand tour as a student, in which his encounters included time with Henze and with Darmstadt composers. Embracing neither Henze's more conventional aesthetic nor the more avant-garde Europeans, Maxfield returned to the US as an enthusiast of Cagean techniques and, in particular, their application to electronic and magnetic tape media. He succeeded Cage as an instructor at the New School and his students included La Monte Young and others associated with Fluxus and Judson Dance. Aside from his invention with improvising complex electronic instruments from minimal means, Maxfield was a virtuoso splicer, working as an editor for a classical record label, for which he once — or so the story goes — inserted a four measure repetition into a well-known classical warhorse which went undetected by critics.

The importance of Maxfield to the development of a live electronic music aesthetic should not be underestimated. In addition to his compositions, Maxfield produced a pair of essays (initially printed in An Anthology, edited by Young and MacLow and reprinted in the Childs/Schwarz anthology of writings by contemporary composers) that outline possibilities for restoring spontaneity to the performance of recorded media — including parallel live performances, treatment of the tape recorder as a live performance instrument, and creating new versions of tape compositions for each performance — that remain vital ideas today. Those essays, and the LP of Maxfield's music put out on Barney Child's Advance label, were important to me from high school days, and I am sure were a great influence on many of my contemporaries.

Maxfield's biography, artistically, is marked by the change in allegiances from youthful neoclassicism to an academic 12-tone style and to the experimental tradition, a path that was not altogether unisual. According to an unpublished memoir of Maxfield by his companion (who happens to have lived for many years in the house next to that of my parents in Southern Californian, the lattice of coincidence being what it is...) through much of the 1950's, the most turbulent change — to experimental music — was not only musical but accompanied by personal upheaval, and Maxfield's life and psyche were increasingly out-of-control; his was not one of the stories of someone who successfully negotiated the 1960's, ending instead, as Slonimsky put it, with "self-defenestration" from a Long Beach hotel.

Sunday, November 02, 2008

Morning,Idle

A piece for household use:

Morning, Idle

for leaky faucet, three china teacups, chopsticks, and whistling teapot

Fill the teapot, place on stove & set to boil.

Adjust the faucet to a steady, moderate, drip, possibly amplified by an inverted bowl — floating, perhaps — placed in the sink immediately below the faucet.

Pour water into the teacups so that each cup has a different pitch, arrange the cups before you from low to high. (The water must be freshly poured or the cups will have a deadened ring).

Listening closely to the faucet, repeatedly strike the edge of the lowest-pitched teacup as precisely as possible between each drip.

Now alternate between the low and the middle cups, repeatedly,

then, repeatedly, between the low and the high

then, repeatedly, between the middle and the high.

Take a leisurely pause.

Now, doubling the speed, so that every second strike coincides with a drip, play the three cups in sequences,

repeating first low then middle then high,

then repeating low then high then middle,

then repeating high then low then middle,

then repeating high then middle then low,

then repeating middle then high then low,

then repeating middle then low then high.

Take another leisurely pause.

Now, double the speed again, so that every fourth strike coincides with a drip,

repeating first low then middle then high,

then middle then low then high,

then low then high then middle,

then high then low then middle,

then high then middle then low,

then middle then high then low.

The piece ends when the teapot whistles.

With practice, adjust the amount of water in the pot and the number of repetitions to an optimally matched duration. Experiment with versions in which the the strikes additionally accelerate to three or five times the original speed. Other gray codes may be substituted for the sequences above. Experiment with versions with more than three cups or in which the cups are moved slightly or the chopsticks tilted into the cups so that the pitches are varied. If the tempo of the drip is slow, additional strikes of the chopsticks against one another may be interpolated between the teacup strikes.

2.11.2008